CHRISTELLE JEANNE LACOMBE

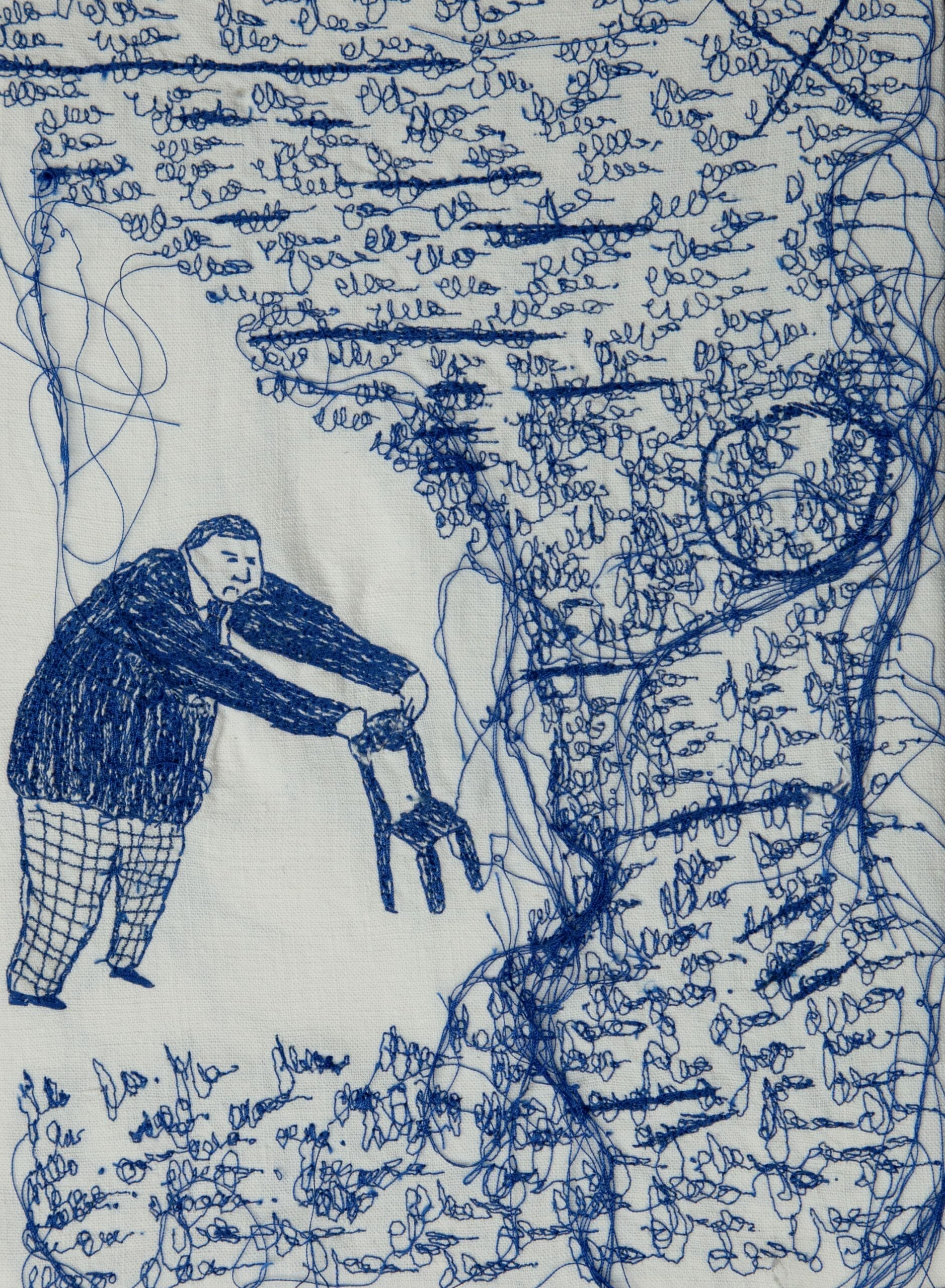

Christelle Jeanne Lacombe, born in 1969, lives in Paris, where she works as a psychoanalyst with teenagers experiencing psychological issues. She combines this profession with her work as an artist through textiles, ceramics and engraving. For her, artistic practice and psychoanalysis are made of the same texture: her research is fuelled by the interweaving of words and sculptural language. She has gradually oriented her artistic practice towards textiles, sustained by a focus on the questions of writing in connection with the body. During her participation in the current exhibition at the Museum of Embroidery and Textiles in Valtopina, we had the opportunity to ask her a few questions.

How did you come to embroidery as a mode of expression?

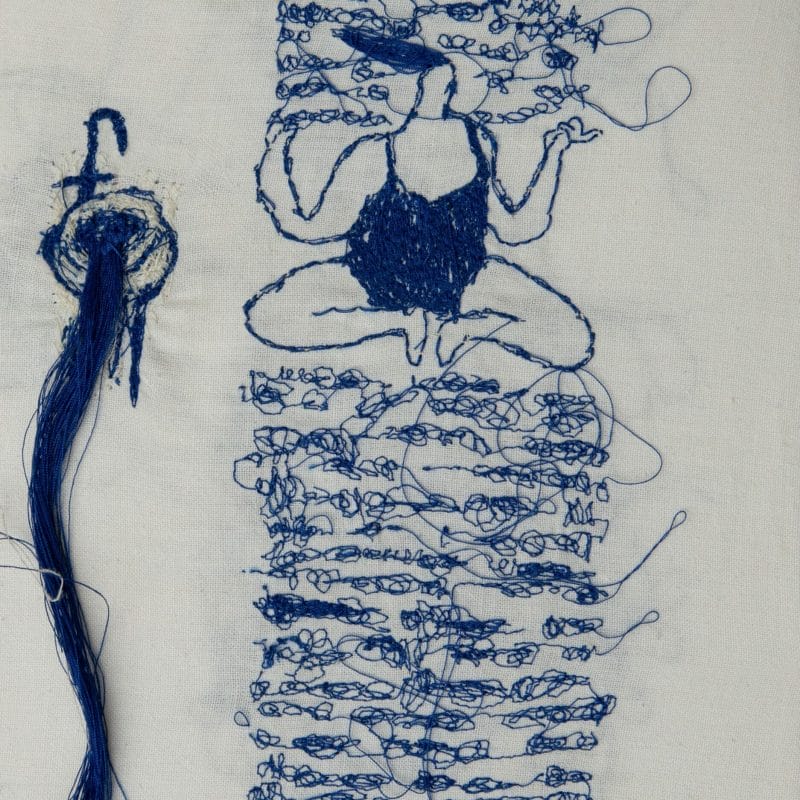

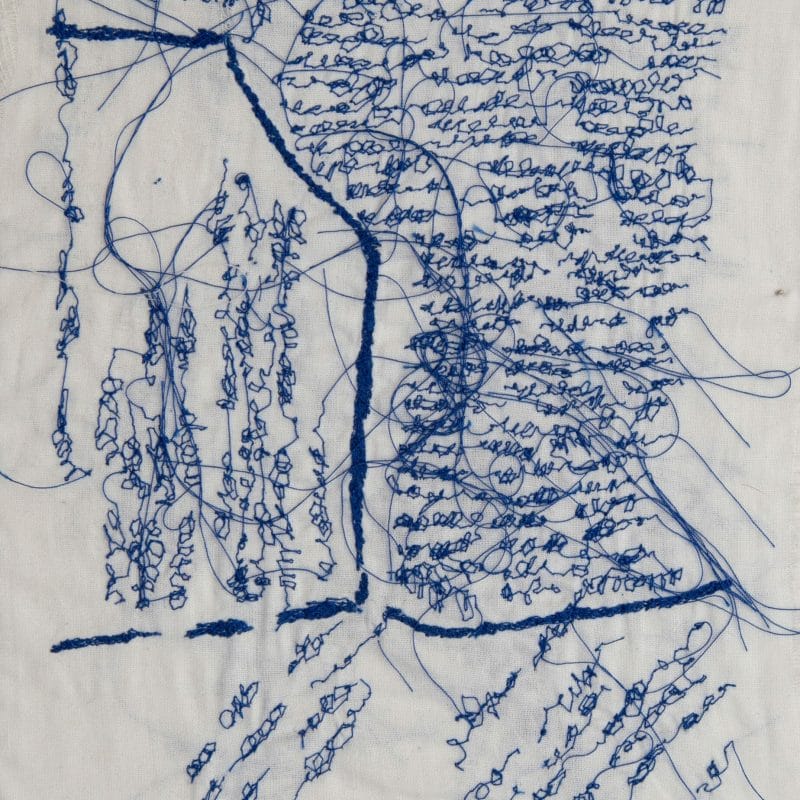

Quite late on, only around ten years ago. Several things gradually led me towards this work with textiles. As a psychoanalyst in an independent practice as well as in a day centre my work with teenagers and use of mediations, including textile, pointed the way. We get together for the duration of a leisurely stroll comprised of words and gestures. Gesture weaves its way like the flow of words wandering slowly keeping time with the activity.

Stitching, assembling, cutting, produce a piece of textile art. A blossoming, like an attempt to ground the living being in sensory soil. The sensuality of the textures and the very specific gestures related to working with textile seem to afford certain borders to enfold a body and a world from day to day, stitch by stitch, allowing small revolutions, framing spaces using hand-made lettering.

It is through these encounters that my creative work has gradually led me towards textiles sustained by an intense consideration of the tensions existing between language and the human body.

My creative process is woven with several threads, ceramics, engraving and textiles.

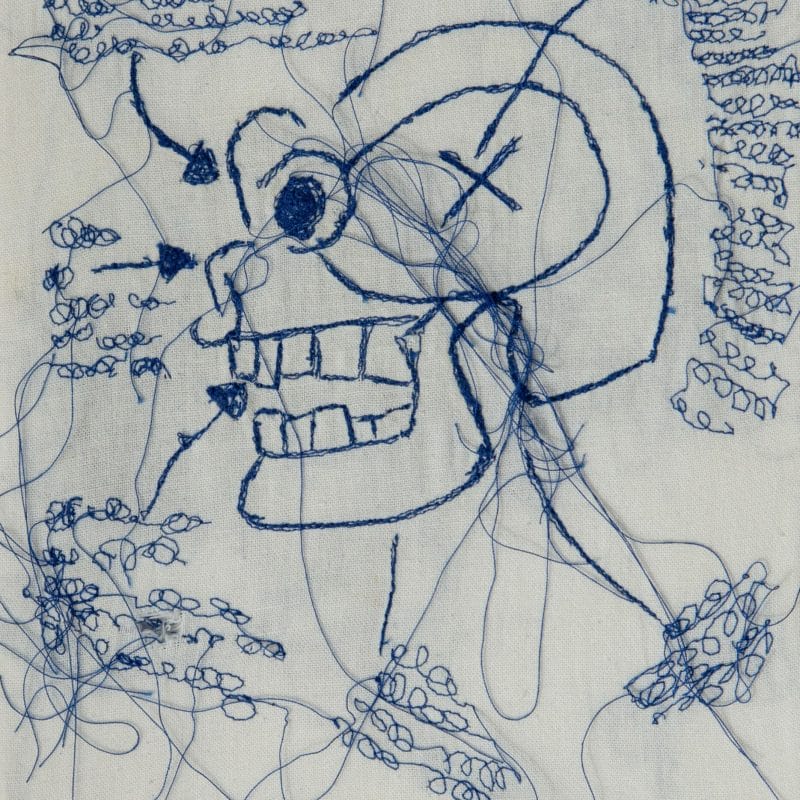

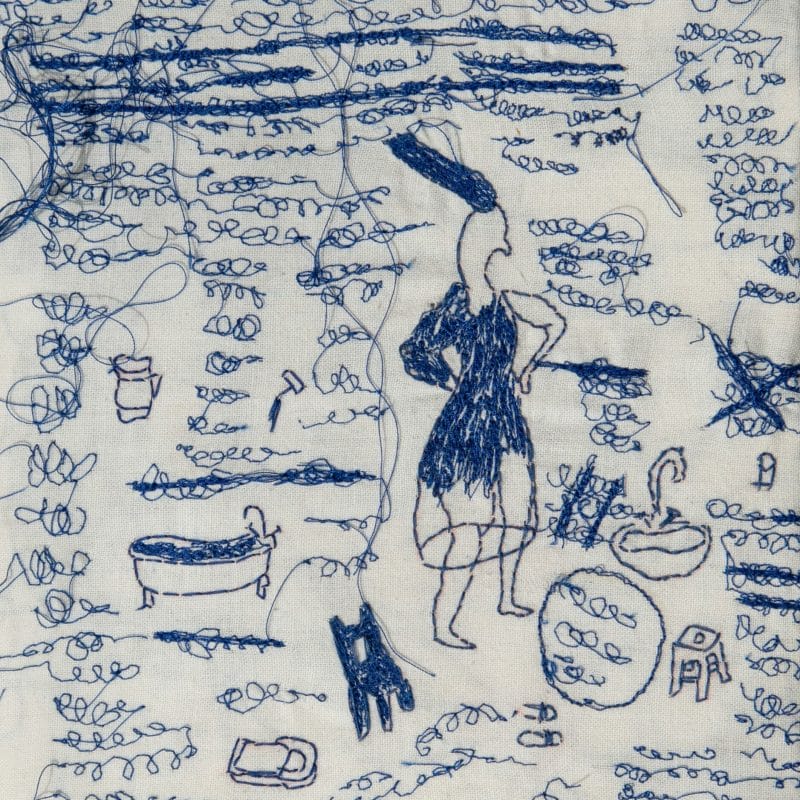

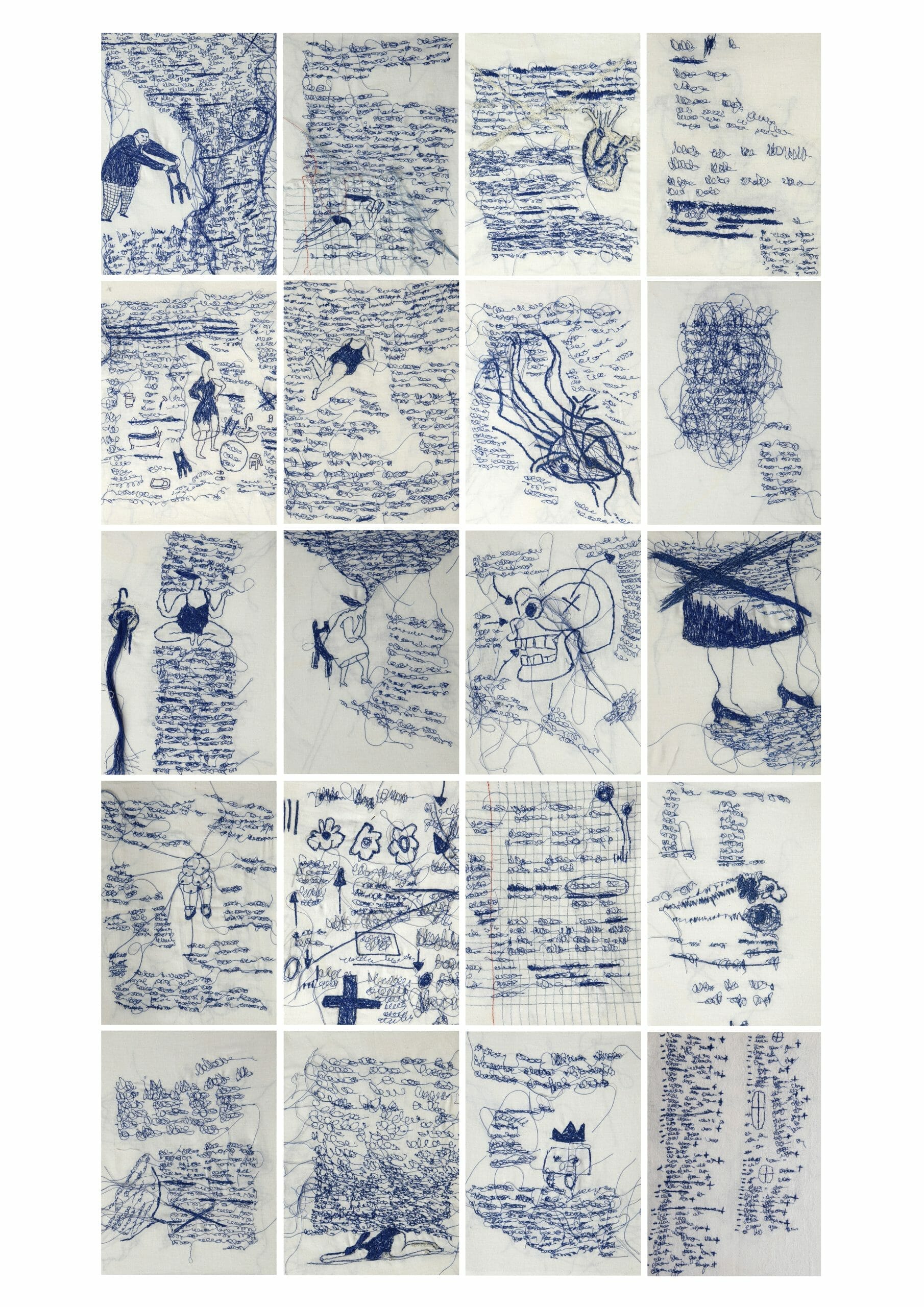

A first link occurred between ceramics and textiles producing ‘body fictions’, the possibility of playing with the lightness and suppleness of volume. The elasticity of fabric contributes to dispelling the conventions of a figural grammar. Forms without faces, without ideas or intelligence were generated.

In parallel, I was developing my engraving work. The fabric, the circles, the knotting asserted themselves like writing on copper plates and linocutting.

As a child I would knit samples and my mother, slightly puzzled would say ‘what yarn are you spinning girl?…it doesn’t make any sense’ while she applied herself with real expertise to needlework and knitting which, for many years, excluded me from her savoir-faire.

‘Spinning’ here is a métaphore as popularly used in the expression to indicate that you are fabricating and telling stories.

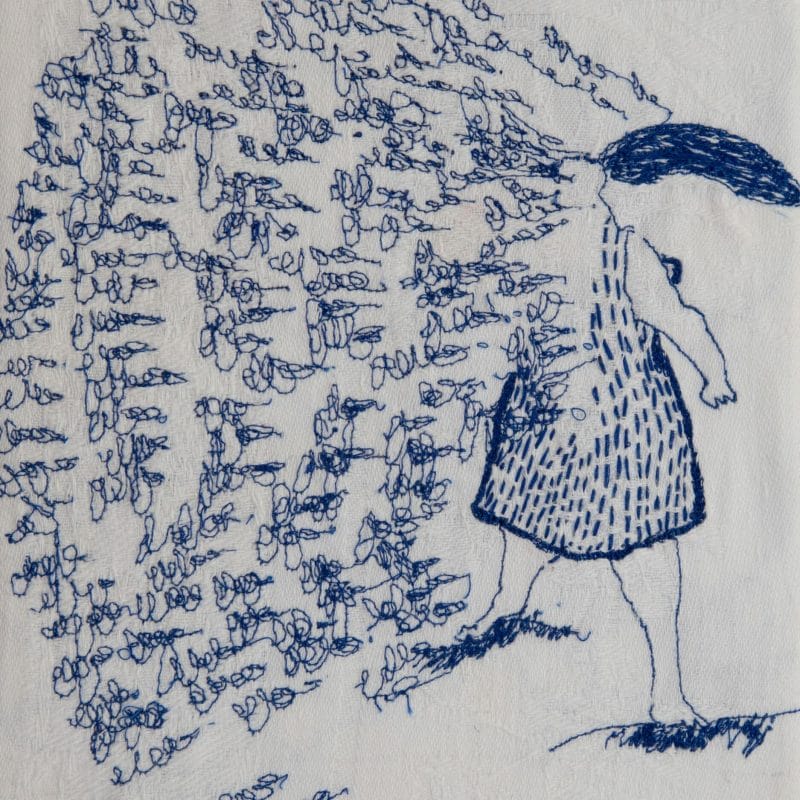

Embroidery was a process mastered as early as the Middle Ages allowing the decoration of fabrics and tapestries and giving a stage to real storytelling. This need to produce fictions just as the poet opens the way to reveal a significant act, like the act of invention. Weaving a fiction was necessary to conserve a space for nonsense, to steer clear of misguided meaning. An essential condition for the letter to carry out its work of cutting, turning, taking, leaving. The letter can be the expression of the body as long as it is in motion.

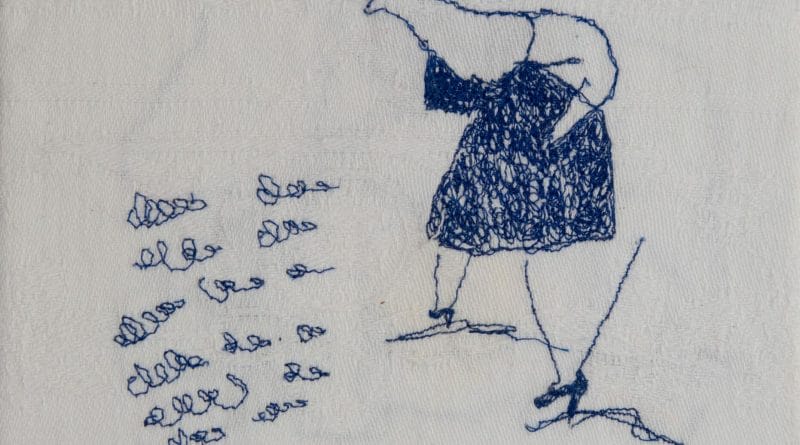

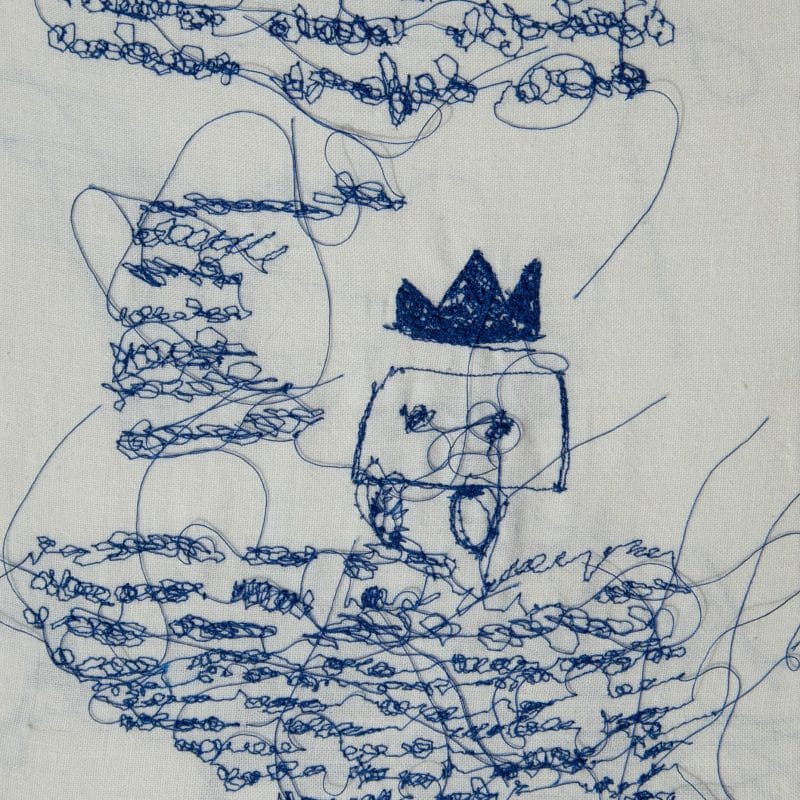

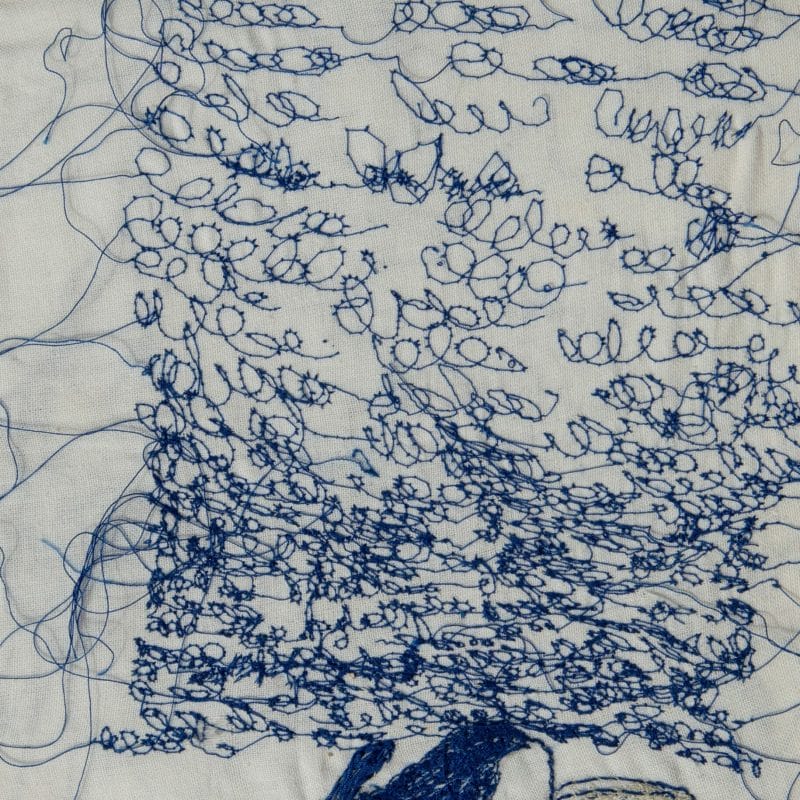

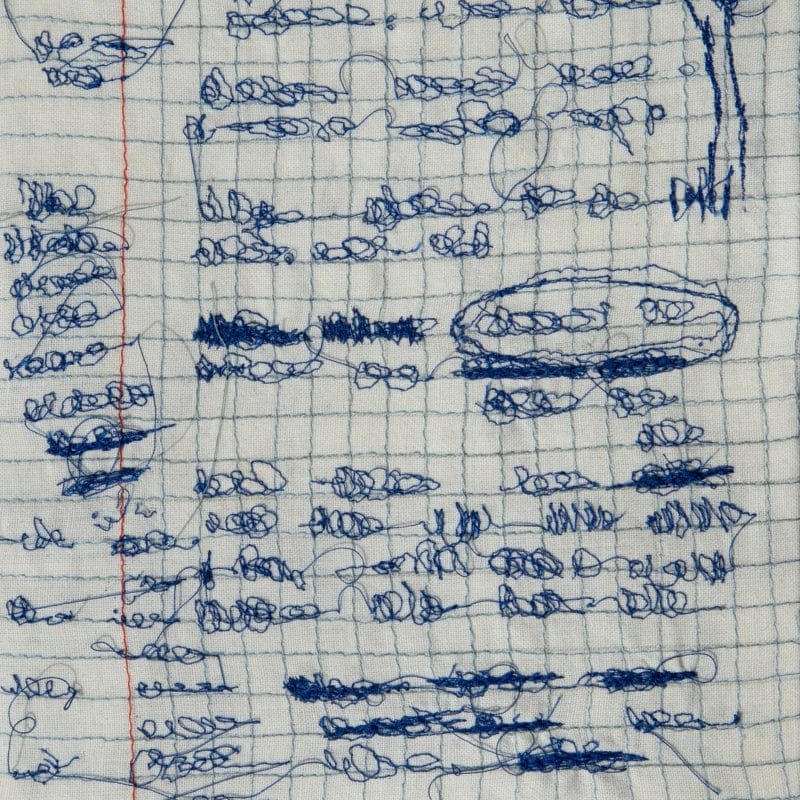

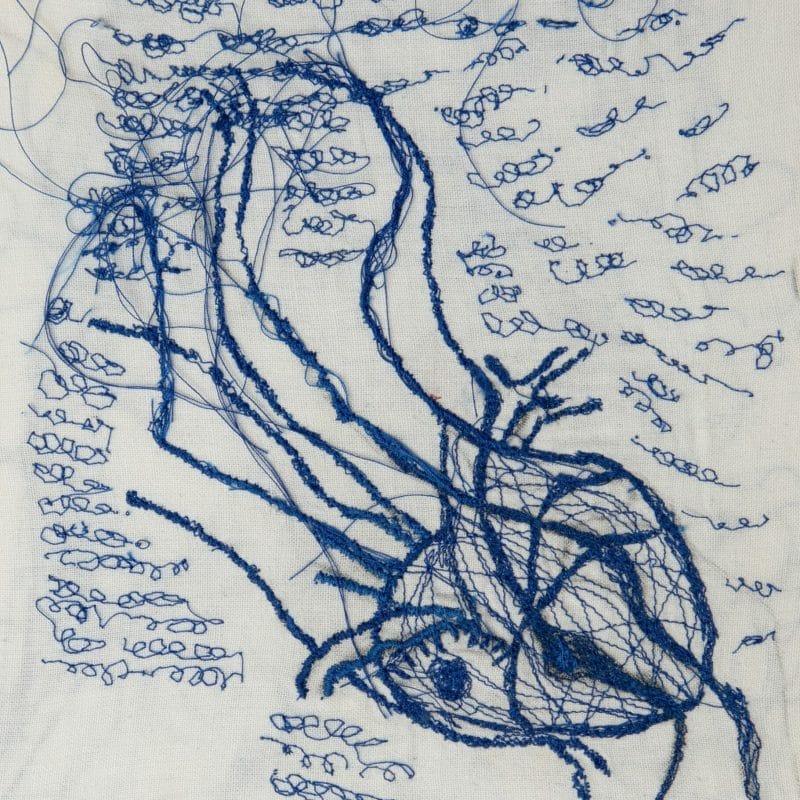

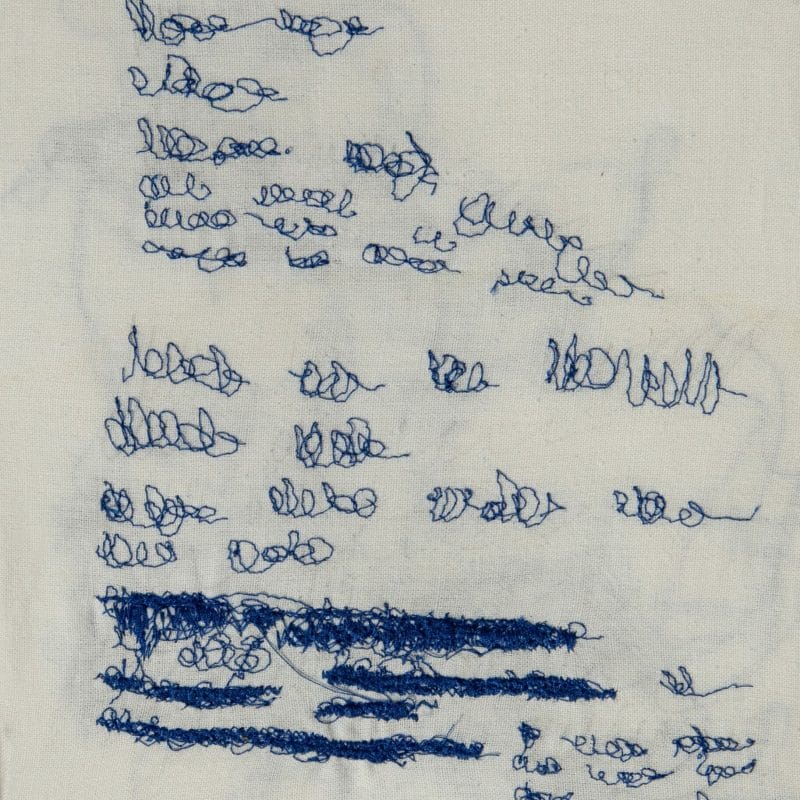

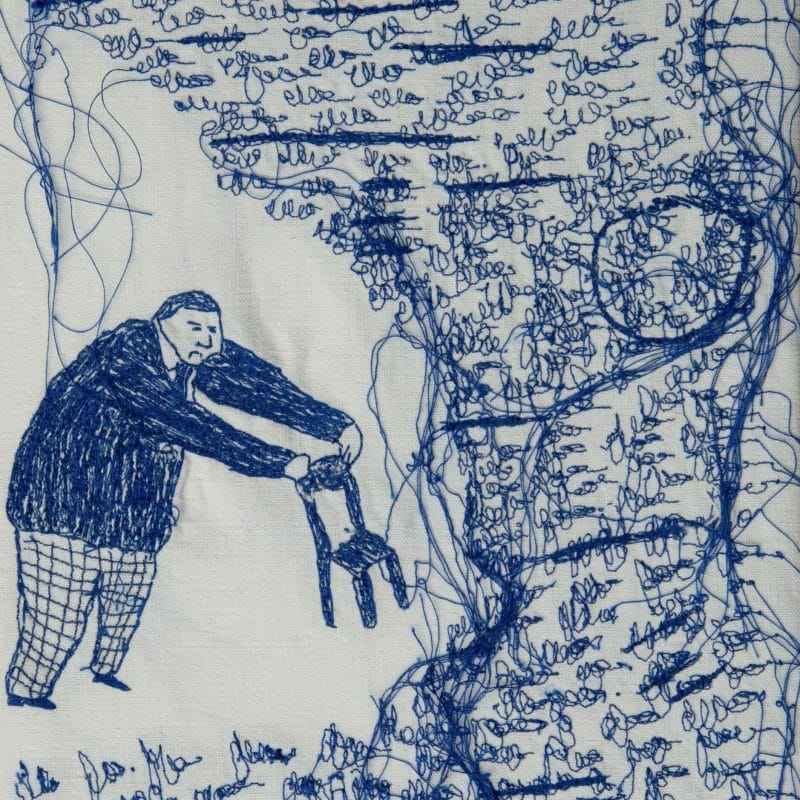

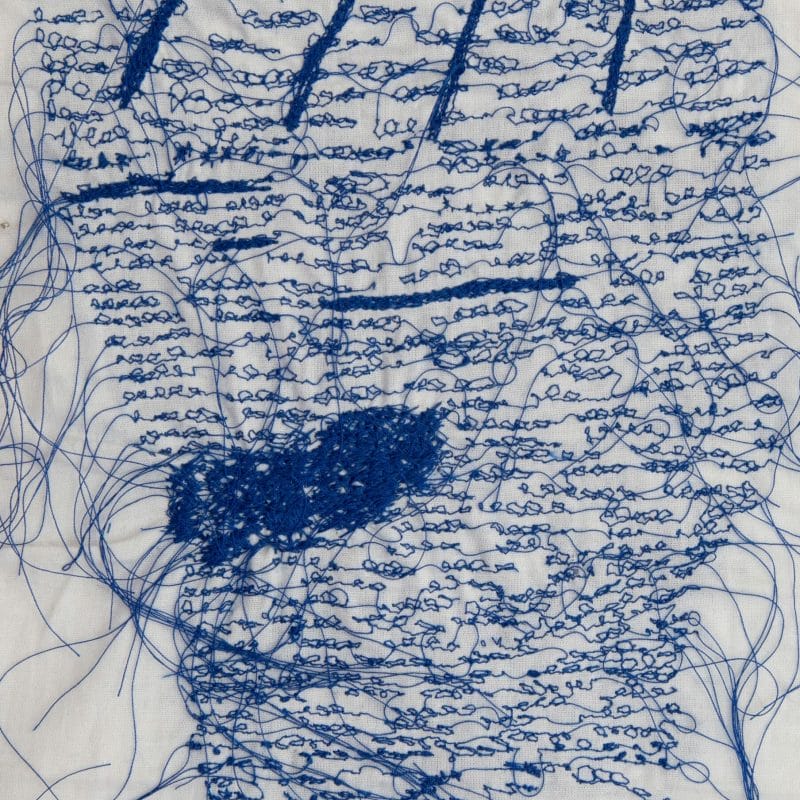

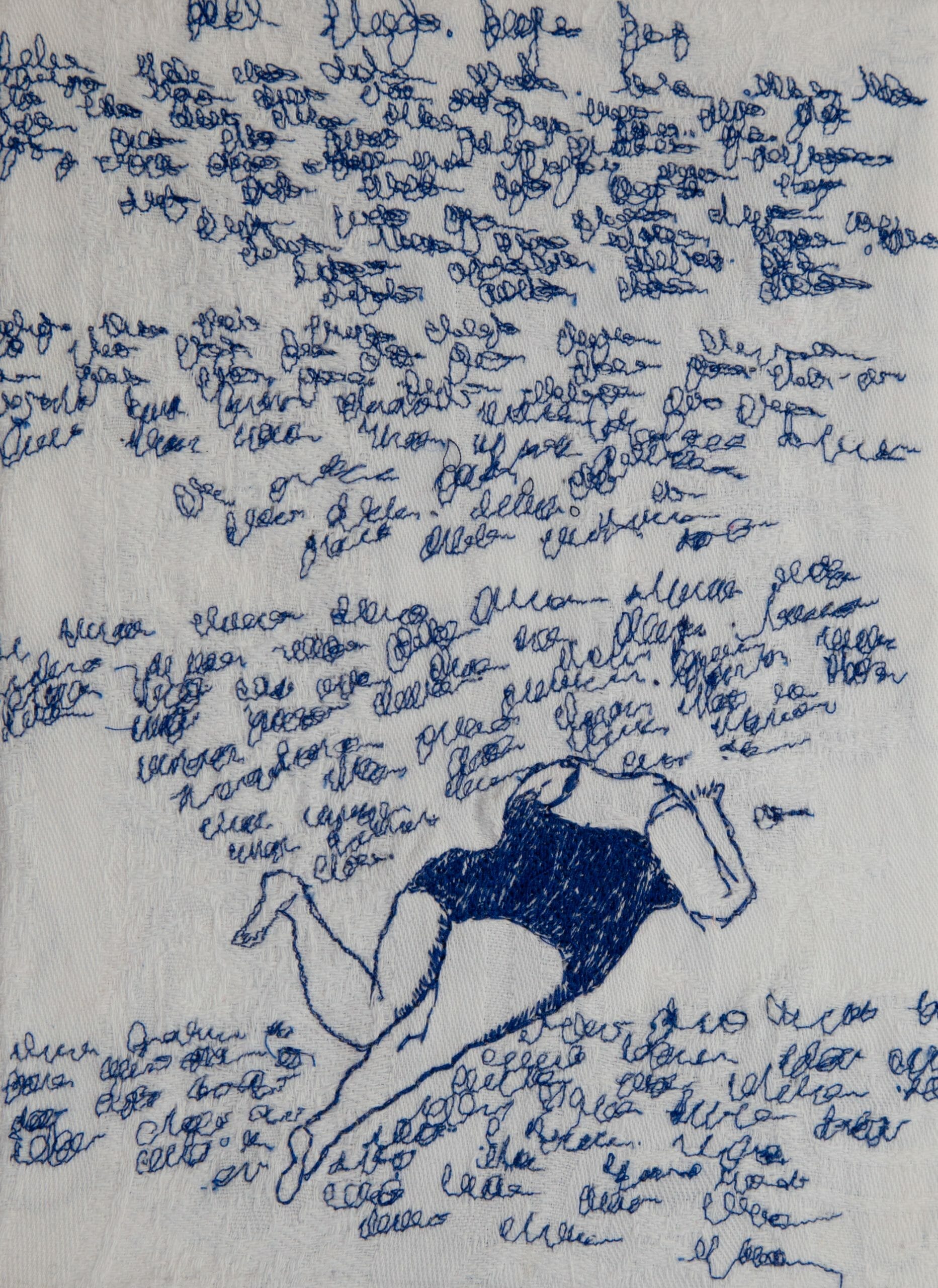

The incontestable expression of your work is the dense pseudo script embroidered in blue using graphic signs evoking fluid and rapid cursive script exempt of explicit meaning. What is the significance of these signs?

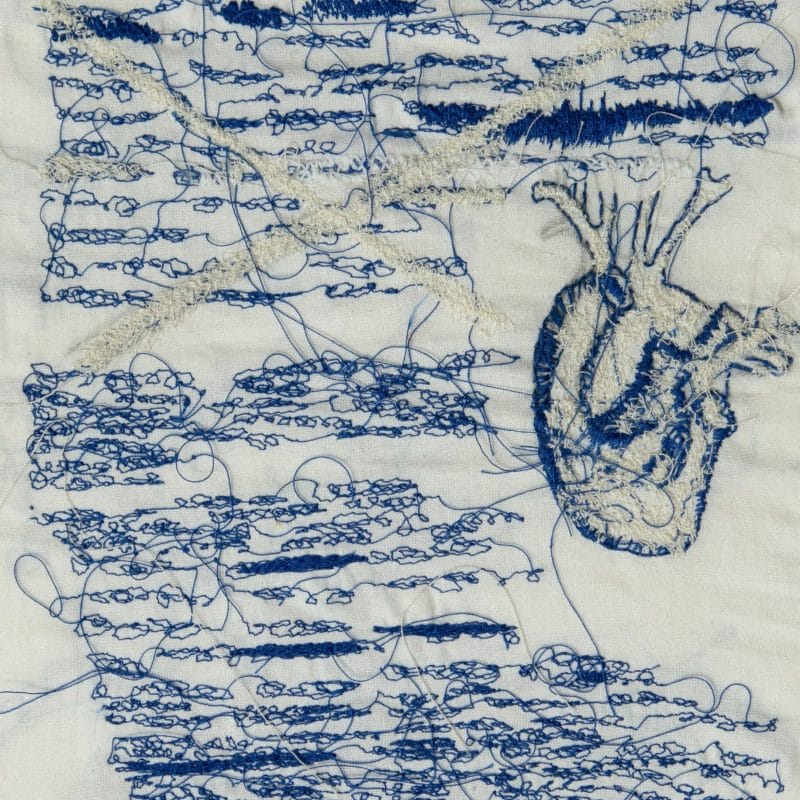

Human beings, immersed in language, are overwhelmed as speech presents itself, overturning, hitting the mark, like words coursing through veins.

The whole body reacts and is overwhelmed by the enigma of these characters and letters.

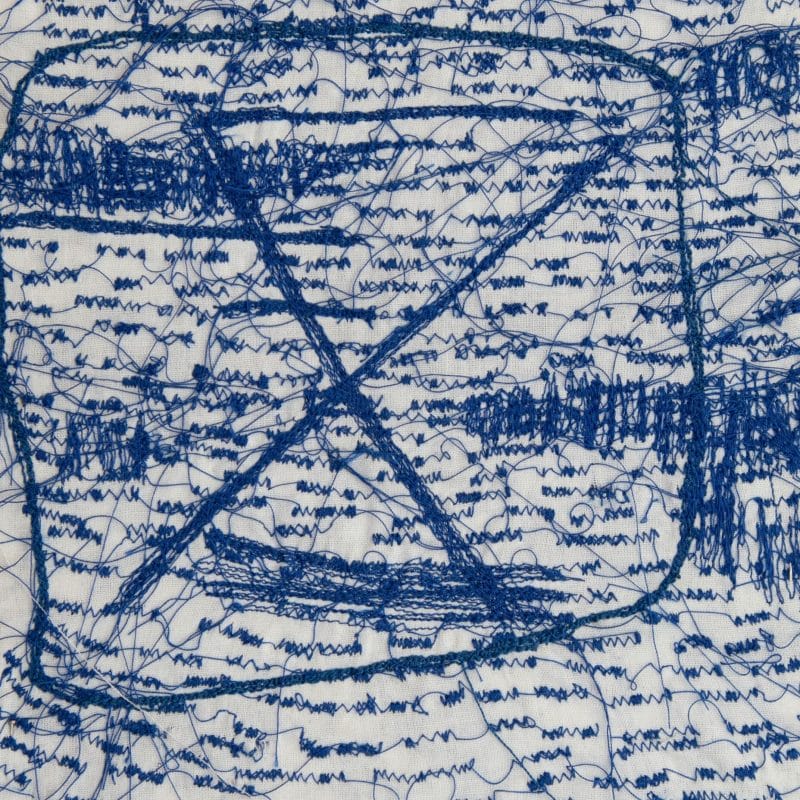

The etymological roots that underlie the phonological proximity between ‘text’ and ‘textile’ forever bond the notion of text to the lexical field of words used in textiles. The creator’s subconscience ponders obsessively over what seems to emerge too clearly as obvious. Like Penelope who stitches and unpicks her tapestry, the work of the poet in Homer’s tales, ties and unties the poetic subterfuges of meaning. Derrida’s words come to mind, the essence of a text resides in the dissimulation of its arrangement, the layout and combination of threads that make it up. ‘A text is not a text unless it hides from the first comer, from the first glance, the law of its composition and the rules of its game. A text remains, moreover, forever imperceptible. It’s law and its rules are not, however, harboured in the inaccessibility of a secret; it is simply that they can never reveal themselves, in the present, as anything that could rigorously be called a perception’ (Jacques Derrida, La Dissémination, Le Seuil 1972 P.71)

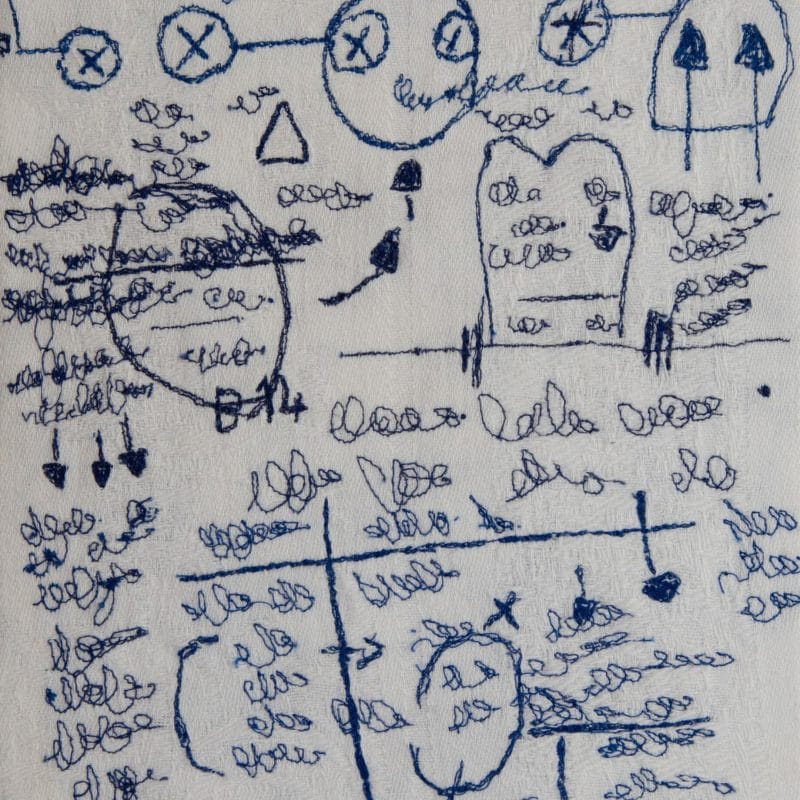

Architecture, ruling and structure are preoccupations to give form to a fictive body text no less essential to counter the voracity to understand, but also to quieten the excesses of the body giving rise to sterile lands.

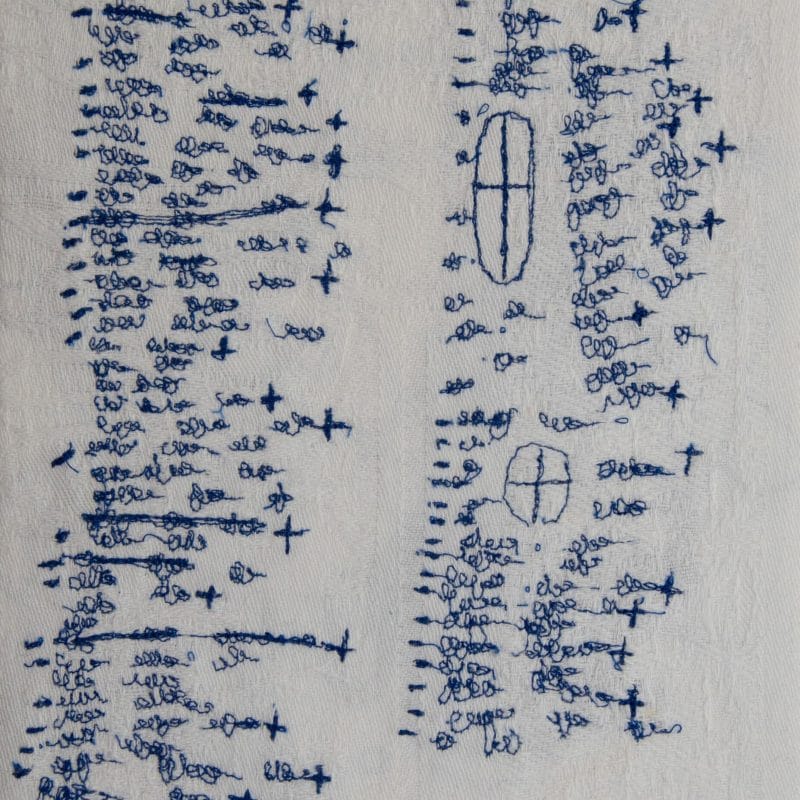

The sewing machine here becomes almost a typewriter. A sort of hand-made writing machine! In turn lazy or impatient.

Cursive script is a form of writing that invols the body, its energy, its movement, its uncertainties, its hesitation and urgency to lay itself down upon a medium.

From ‘jumble’ to ‘doodle’ marks become writing. In 1973 during the Encore seminar, in a term close to ‘scribbling’, Lacan talks of writing as ‘doodling’. ‘Writing is a mark that should be viewed as linguistic effect. This is how doodling works…’ (Jacques Lacan, Encore, 1975, St-Amand, Le Seuil, p110, referring to the text Litteraterre and the swarm of language that makes up writing).

In Encore, on 15 May 1973, Lacan says ‘Writing is a mark where an effect of language can be read. When you doodle something, as I also definitely do, this is how I prepare what I have to say. And it is striking that it is necessary to verify writing in this way.”

I like to call this kind of writing sublanguage

In this case, sublanguage illustrates from letter to letter, the seeds that are sown on the blank canvass of textile.

My position as scribe in this work was the occasion to allow cursive script to let sublanguage emerge.

Countering meaning is a prerequisite which allows me to contrast imperfection with the almost perfect mechanics of the rhythm of the sewing machine, like a talking machine. I find a form of otherness in this which allows me to dupe alienation. Within its almost perfect mechanics I lay bare the shortfalls, failings, effervescence, saturation, suspense, fault line, emptiness. This is necessary to allow language to play out and secure off-beat spaces

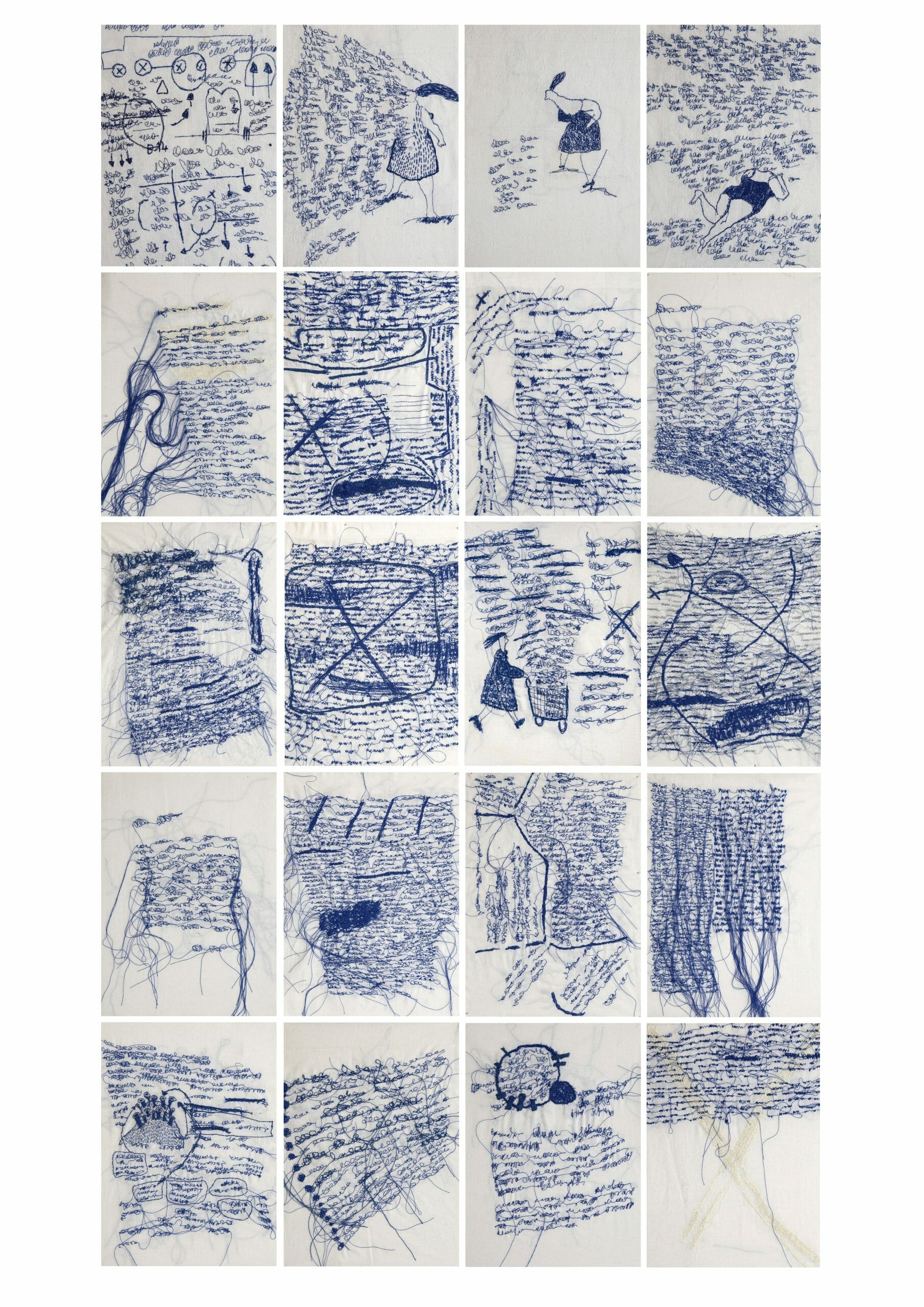

My series of forty ‘letter fictions’ reveals a sort of ‘topsy-turvy’ language. The train of thought is not linear but vacillates from confused to ordered with occasional humour.

Why do you choose the colour blue?

I started my first textile letters using black thread, thinking it more graphic, but the emphasis and significant presence of the black uniformity of our computerised writing led me in search of a colour similar to the pen thus directly evoking hand-made symbols.

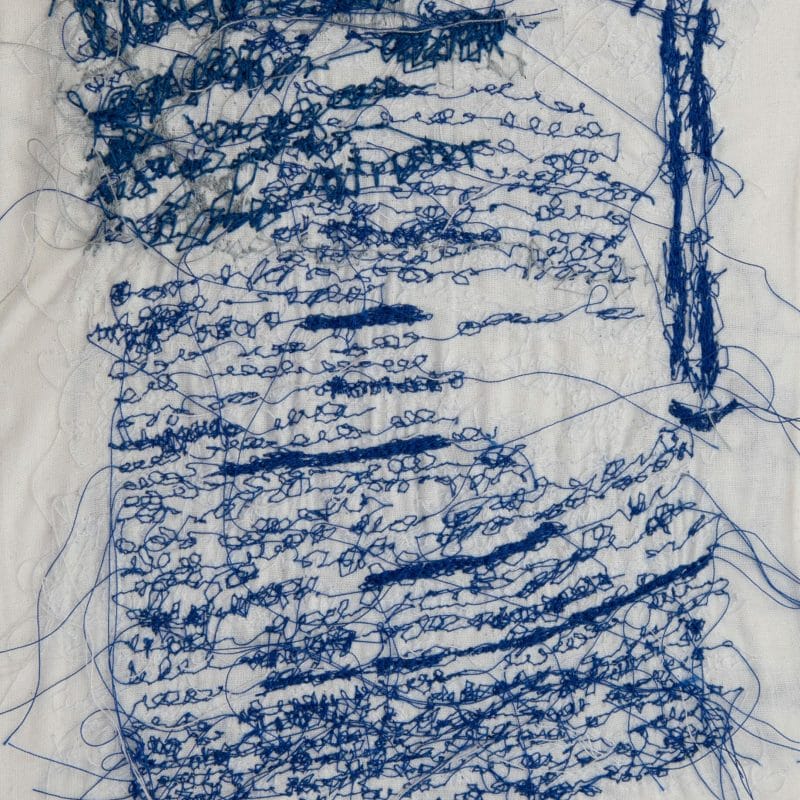

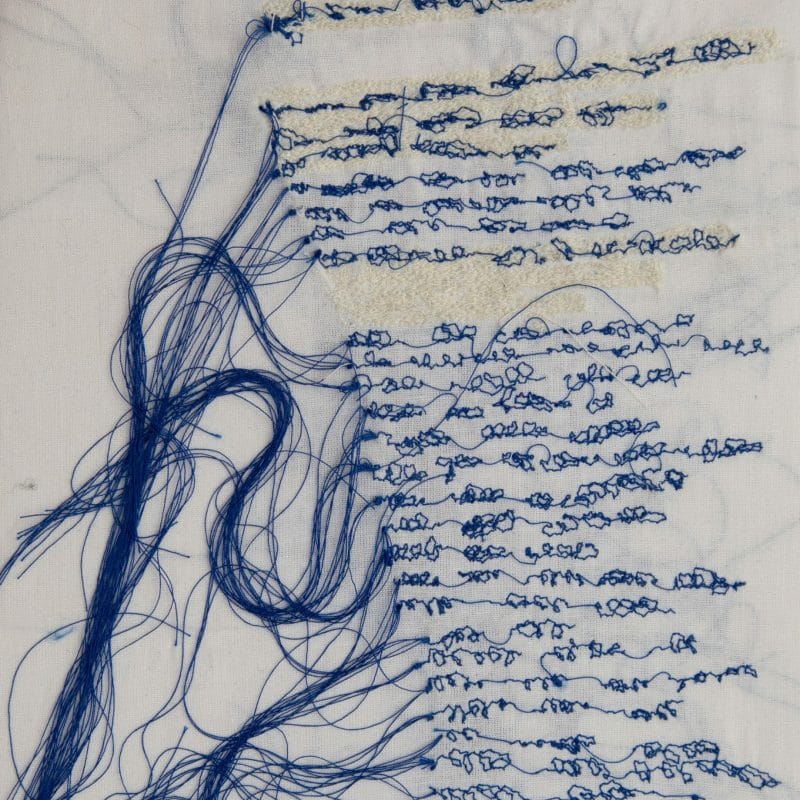

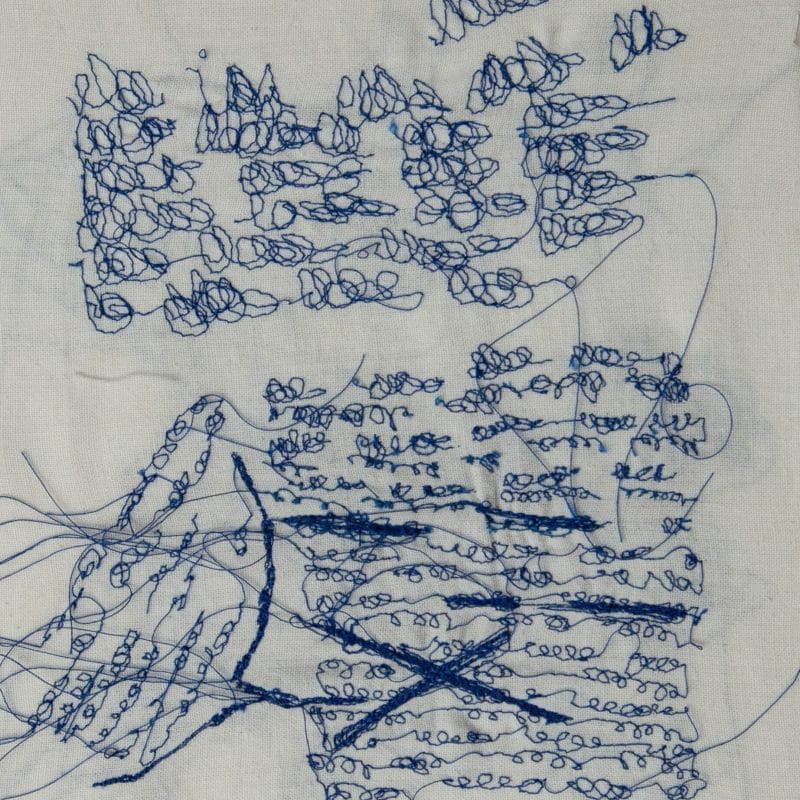

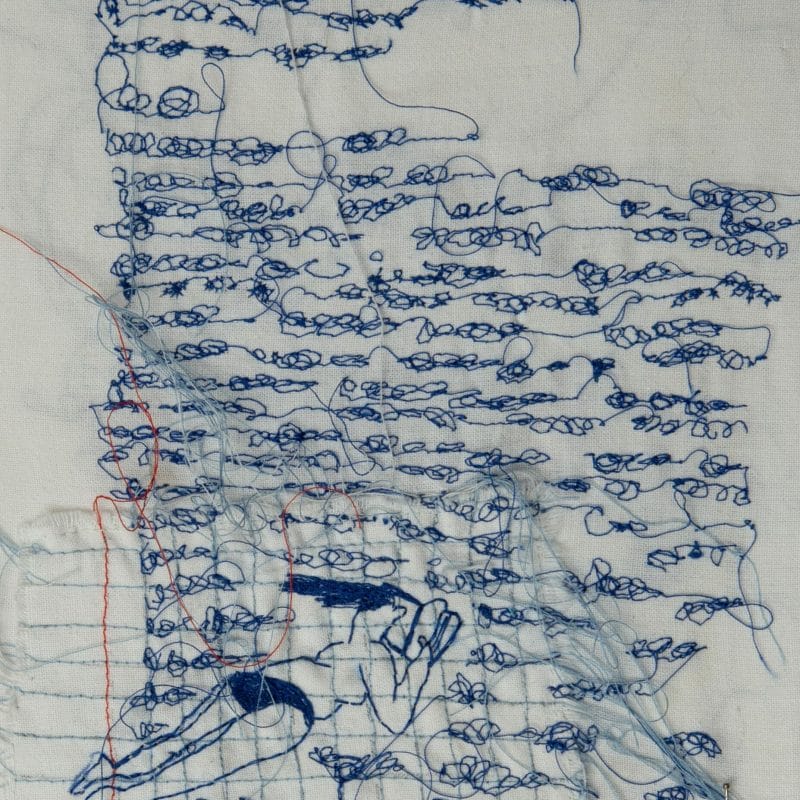

Your embroidery has loose threads. Is this a technical or esthetic choice or is there a particular meaning?

Certain discourses leave you no space, they stifle thinking, are tightly sealed producing no residue. A breach can reveal the underside and the residue which is a necessary factor in desire.

This entanglement worked in the underside of the discourse affords a kind of permanence and also a kind of reserve for the individual. These factors allow both form and content to to differentiate and to combine.

The loose threads are remains, allowing the work to continue. They give body to the remnants. The remnants exist like traces of suspended thread suggesting a possible repetition. In Japanese whatever makes a mark is called time. Time and place are inseparable, the mark becomes the place.

Embroidery is a slow, patient, repetitive exercise, almost zen. Is there a therapeutic and/or cathartic element in this?

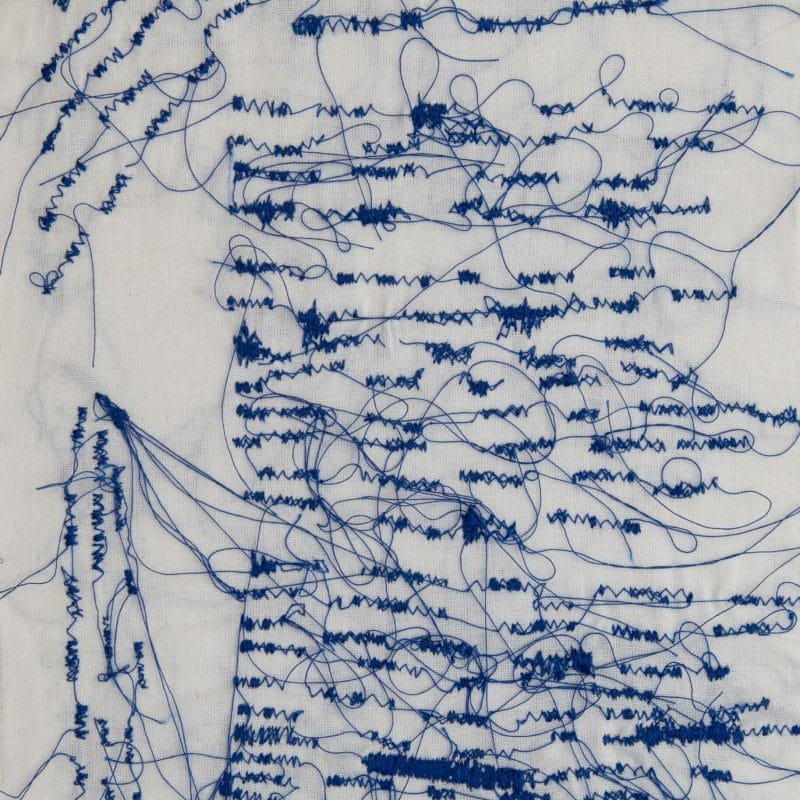

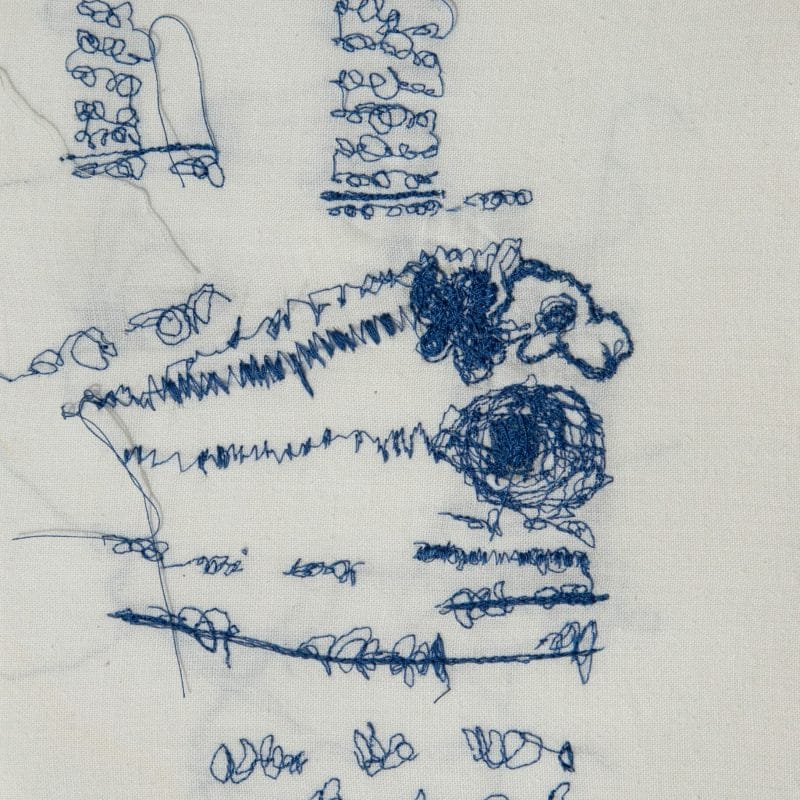

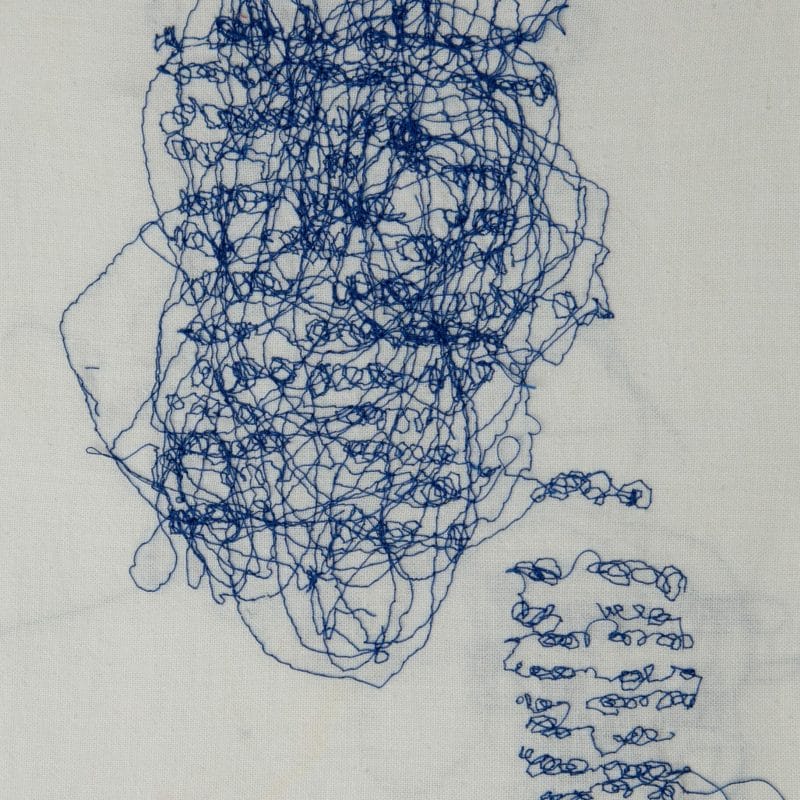

The repetitive movement is carried out under a strong impetus and I need to allow for the emergence of the uncontrolled at the same time as containing it. This process has relevance for me and anchors me in a defined space.

A non-defined time on a dial, a different time I can settle into and be completely absorbed and free. The proliferation of circles opens up a game of renewing repetition allowing unique marks to appear out of nowhere to settle. Each time I take up my work it engenders something singular, mostly related to concern.

This concern, made up of acute doubts, reinforces a sense of anxiety as if for the first time, as if renewing the first awkward steps of the work.

What are you currently working on?

I’m still working on the letter fictions. Stitching and unpicking ‘the said mark’ ‘the said letter’ as it’s essential for the letter to stay alive in this way. I am widening my horizons. I’m embroidering graphics with colours resembling blurry childlike marks. I’m also working on my research on ceramic media. One paralleling the other, no marks traced without an initial woven medium.yarn spun?

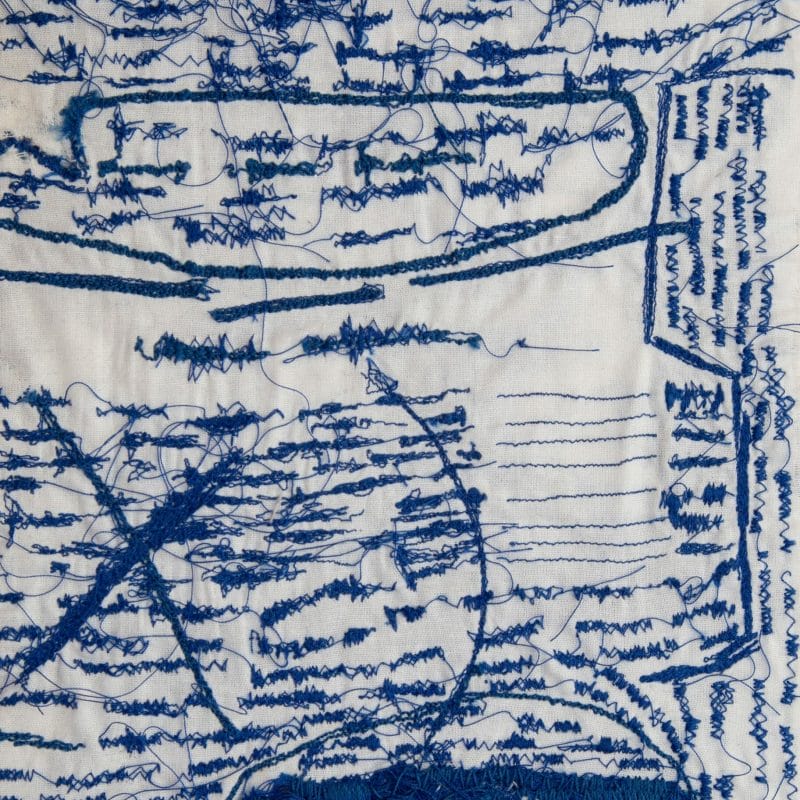

I work with the bare minimum of signifiers. This being the interweaving of the warp and the weft, vertical and horizontal. The principle resides both in the antagonism and the harmony that exists between the warp and the weft.

Greek and Roman mythology have bequeathed us a rich use of the art of weaving. Weaving used as metaphor for the poet weaver, the domestic weaver, the political weaver.

‘ Weaving was already a way of disentangling a great muddle of things so as to put each thing in its place. It’s about intertwining things that are different, contrary, hostile, so as to produce a harmonious canvass, unified and worthy of dressing the great goddess of Olympia’ (John Scheid, Jesper Svenbro, The work of Zeus, Myth of Weaving and fabric in the Greco-Roman world, Errance Publications p19)

This is my way of questioning and challenging the bare minimum of signifiers, what is flawed between body and language, in this in-between space that both separates and unites. Balancing on this ridge, this line of tension set by the tempo of the weaving, working even the texture of a veil, the fluttering alternating veiling and unveiling. As Henri Michaud remarks in this poem : ‘Blindfolded with a tight headband, stitched to the eye, slipping inexorably. Like a metal shutter closed over a window. But it is with the blindfold that he sees. It is with what is stitched that he unpicks, that he re-stitches, with absence that he takes and posesses’

Pace of work

I work in little crevices of time, whenever it is possible. These small spaces free me from excess and ensure that the threads drift freely. The Navaho Indians have a custom which advocates a certain moderation regarding weaving and prescribes cures against the addictions of the art. It is even recommended that weavers do not completely finish their work, leaving space somewhere for an opening.