Interview with Asuka Nirasawa

Asuka Nirasawa was born in Osaka and today lives and works in The Hague. Her works take the form of reflections that draw from different areas and combine popular cultures and traditions of the many countries in which the artist has lived. A legacy of experiences that becomes in her works comparison, dialogue, analysis, synthesis and that gives back to the observer a plurality of thoughts and emotions. Moving across continents has nourished the artistic path of Nirasawa who, in the encounter with the other and the different, has found the key to her art, redefining, time after time, the contours and objectives of her artistic and human research. A journey that I have ideally made with her through this interview…

Synchronicity, Time 1, 2018 / silkscreen print, digital print, ink on fabriano paper / 59.4 x 42 cm / photo credit; Asuka Nirasawa

How and why did you start inserting fabrics in your works?

I have always been attracted by the beauty of fabrics. I had early experiences in researching fashion design and clothes making. This culminated in my own awarded-winning design for a KIMONO in 2010 while working in the traditional cloth dyeing industry in Kyoto.

Subsequently, it was natural for me to incorporate fabric into my artwork. The first time I incorporated fabrics into my artwork was in South Africa when I participated in the Bag Factory Artist in Residency program in 2016. There were many large fabric shops near the Bag Factory. Casually I stopped by and saw the designs of African fabrics there. I was blown away by the vigorous, dynamic, and yet surprisingly simple designs. They were full of the joy to live; primitive yet modern. Joy ran through my whole body and I felt inspired so that I couldn’t help using them in my work.

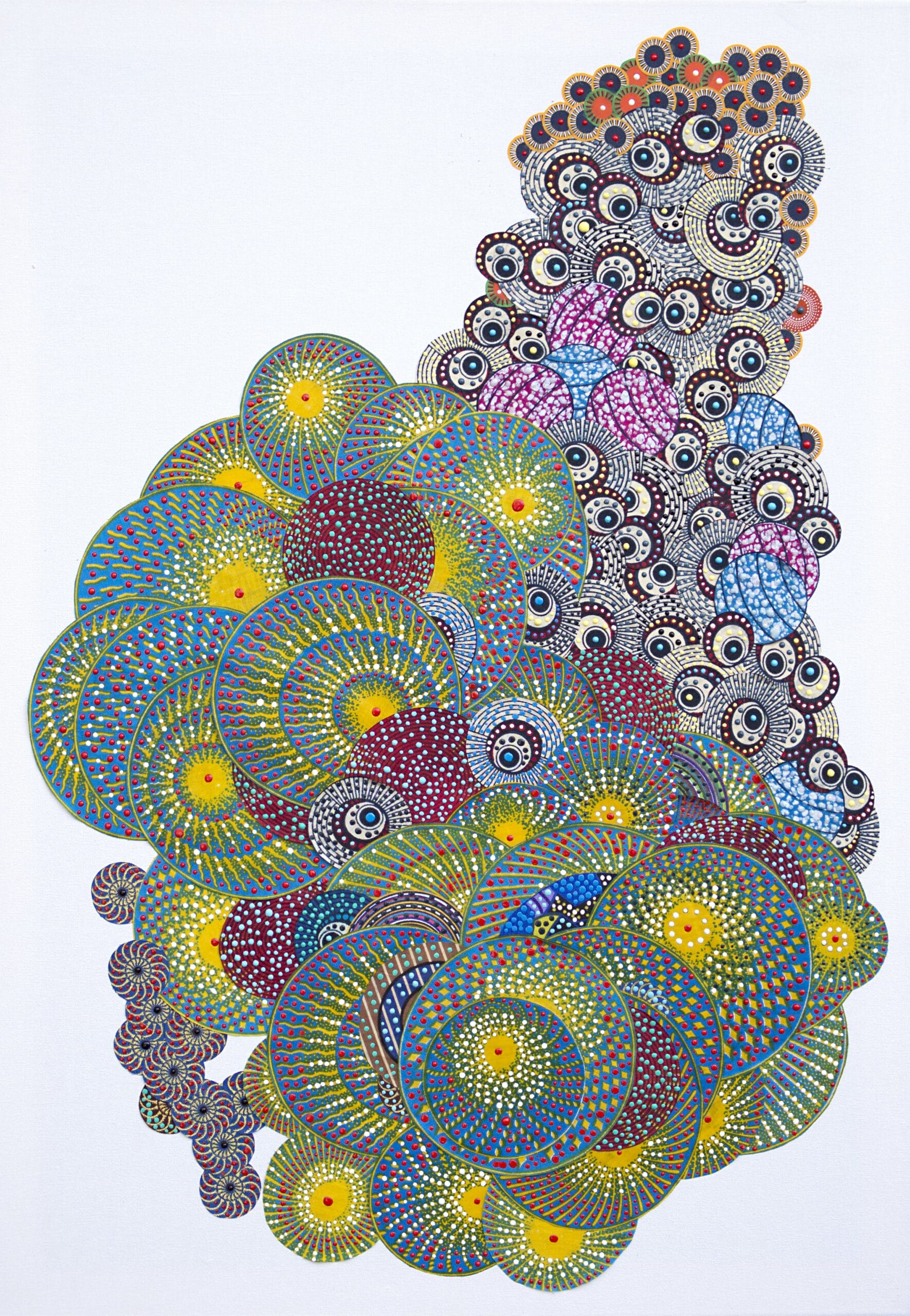

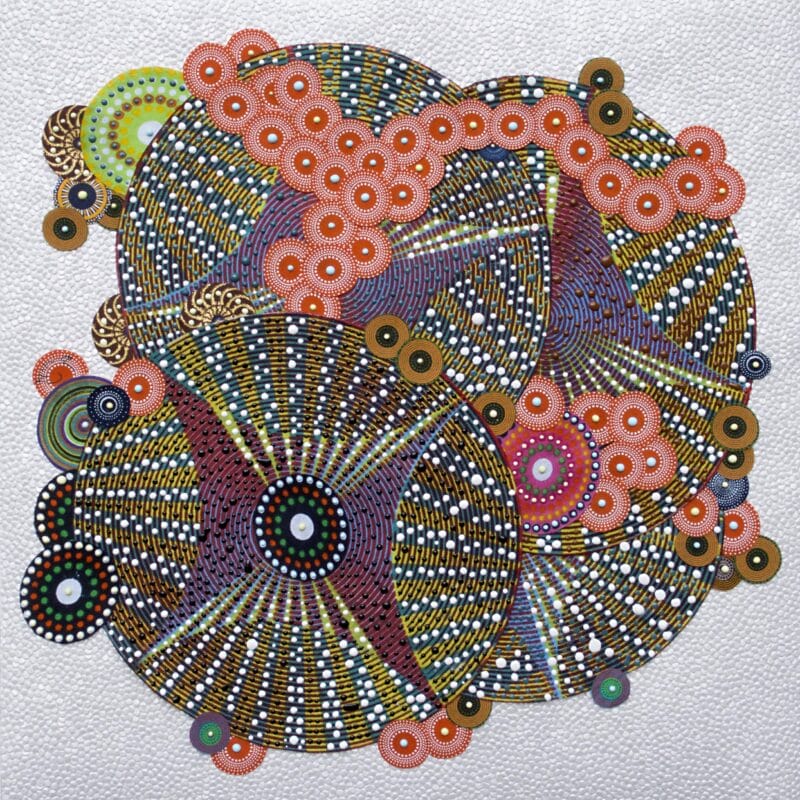

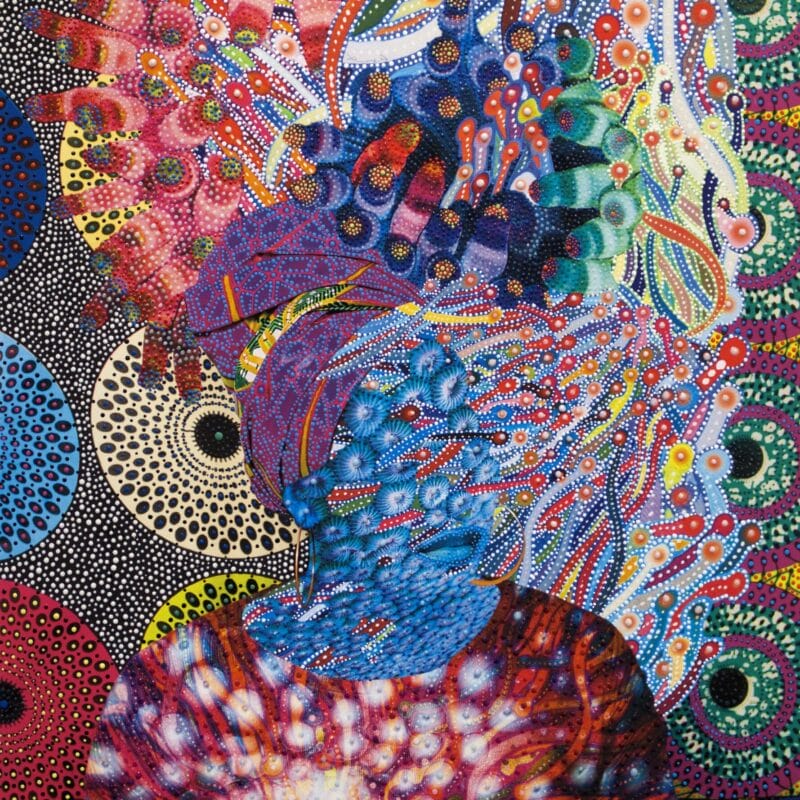

Cytoplasmic Division 2, 2017 / fabric and acrylic on canvas / 84 x 59.5 cm / photo credit; Asuka Nirasawa

You have lived in different countries and continents. How has this wealth of experiences influenced your work as an artist and how do different cultures come together in your works?

I was born in Japan and immigrated to India, Africa and Europe. Now, I am living in Netherlands. My sense, cultivated from my earlier backgrounds, was questioned each time when I put myself into a new environment, with different languages, cultures and contexts. I even found the flow of time in each environment to be different. The fundamental question of “what humans are” always came to my mind. Such questions are essential for me to create each new concept for my work.

Having lived in many different countries, has shaken my identity. Through rebuilding my identity I could return to my root existence. I didn’t know this at the time, but I now realize that this has been an important process for me. I am glad I made these geographical moves at an age between maturity and immaturity, in my thirties. If I were younger than this, I might have adapted to the environment, rather than question myself. If I were older, I may just have rejected the environment due to difficulty in bridging the environmental gap.

Here is another answer about how different cultures come together in my works. I grew up in the city in Japan, one of most orderly countries in the world. Consequently, originally, I have an affinity for detail in my personality. You can often see a huge number of fine dots in my work. But, with the addition of dynamic chaos in India, primitiveness and diversity in Africa and living experiences in Europe today, my thoughts, habits and personality were shaken as more complexity and diversity were added. In this process, I have always found conflicting elements in different cultures, such as sensitivity and dynamism, modernity and primitiveness, order and disorder, which I then fused into my work.

Color occupies an important position in my work. Through studying the colors from different countries, my use of color has evolved. For example, I used to prefer grey-based colors; so-called traditional Japanese colors. This was influenced by the discipline of Kimono design. Using grey as a standard keynote and applying the three color principles of saturation, lightness and hue, I could manipulate colors variedly and richly. But when surrounded by the intense colors in India and the dynamic life of primary colors in Africa, my grey keynote found endless possibilities, which started coming into in my work.

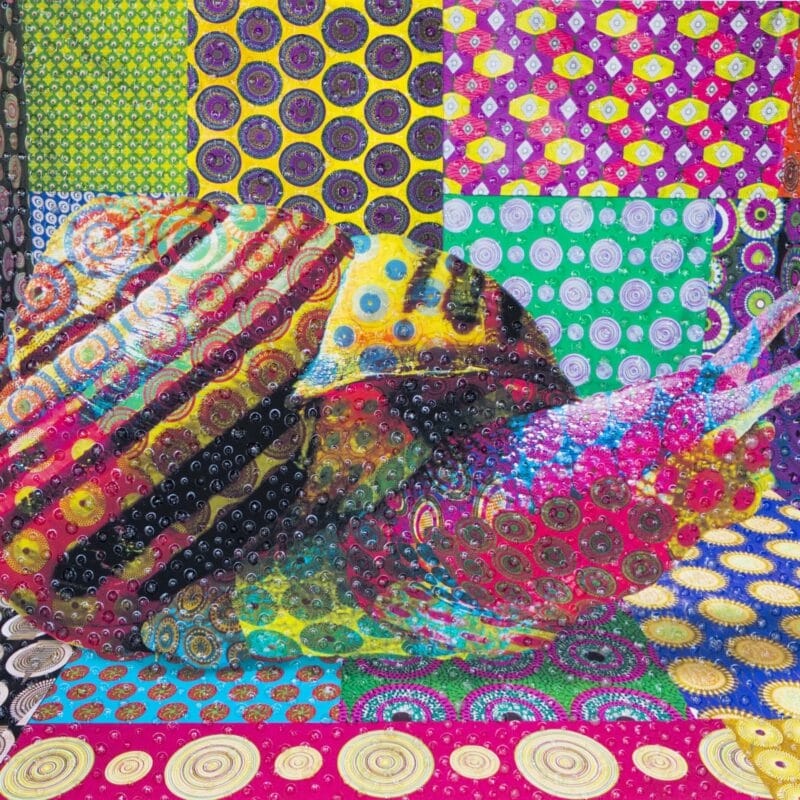

Cytoplasmic Division 1 2017 / fabric and acrylic on canvas / 84 x 59.5 cm / photo credit; Asuka Nirasawa

African fabrics and motifs are recurring materials and themes in your works. How did this choice come about?

As I answered above, my first encounter with the African Continent came from participating in the Bag Factory Artist in Residency program in South Africa in 2016. I was shocked by the African fabric design that I saw for the first time there.

The reason why African fabrics were specifically linked to my work was that there were so many circles and dots in the design. I’ve always used circles (sometimes dots, ellipses, large and small) in my work. Very Japanese-specific, in Buddhism, the circle is the motif of infinity: there is nothing in the middle, there is no beginning or no end, it is the ultimate. The circle represents the entire universe. Many African designs use circles and they also have elements of Asian design. African designs are timeless and universal and I feel familiar.

As my project at Bag Factory, I went around the fabric stores and bought all the types of African cloths with circle patterns that I could find. Then I started to cover the walls, floor and ceiling of a room with them. I used the room for a photo shoot and made portrait works, with various persons posing in front of the cloth background, surrounded by infinite circle motives (for example in “A medium of a requiem in a cell”, 2017). After that project, I moved on to cutting out the circles printed on the cloth and I started using the circles themselves: the potential of my work expanded.

Remembered ritual, 2019 / installation with 200 circular cut African fabrics, human hair, cotton, thread / 120 x 160 x 180 cm / photo credit; Asuka Nirasawa

For your works you often draw from science – from biology to psychiatry. What is the genesis of your works? How was the idea born and how is it transformed into a work of art?

When I encounter emotional phenomena, albeit from my own emotional responses or from the manifestation of emotions in the actions of other people, my initial interpretation thereof is mostly conflicting and vague. They need to be verbalized and analyzed. How difficult it is to express them, but how interesting to attempt that expression? That is why I borrow from the sciences. I believe the concepts in science can help to verbalize concepts in art. I borrow from the context, theory and logic. I find that the theory of science can be my eye-opener. As a constant task, I have wondered how scientific theory explains emotions.

For example, there is a series of my prints titled “Synchronicity” (2018). This is a concept advocated by psychologist Carl Jung. He coined the word “synchronicity” to describe “temporally coincident occurrences of a causal events.” Jung became convinced that everything in the universe is intimately connected. That suggested to him that there must exist a collective “unconsciousness” of humankind. I used his concept to name this series of my works, because the works match his theme: each collage consists of seemingly, unrelated images. I made these works while being conscious of my unconsciousness (meaning the deliberate avoidance of a conscious motive). However, I did not try to follow Jung’s concept when beginning the works (and I was indeed unaware of it). But, maybe because of interconnected chance, I later considered that Jung’s theory provided some explanation of the resultant artwork.

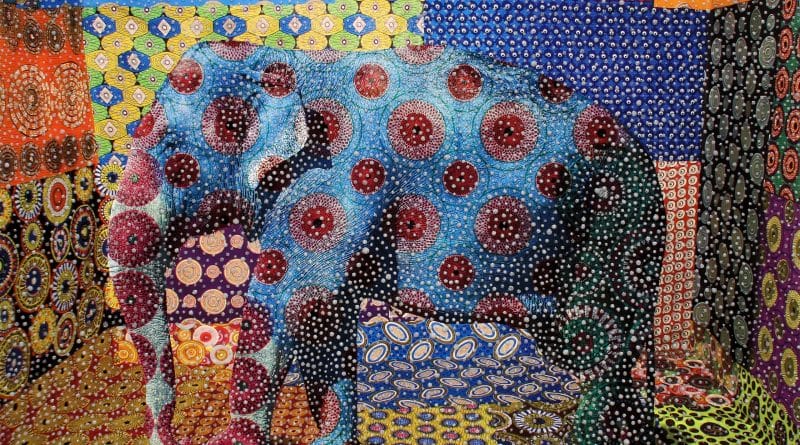

Acne entropy, 2017 / installation with african fabrics with circle motives,at Gallery Nomart Japan) / photo credit; Asuka Nirasawa

“Remembered ritual” is among the most recent installations. How have your works changed over time, from the beginning of your artistic experimentation to today – in the relationship with space, for example?

In relation to space, my works have undergone a truly dramatic change. For a long time, I have most undeniably perceived space planarly. This is a typical aspect in Japanese art: the perspective of capturing three dimensional objects as if they were flat, for example, Ukiyoe as created by Hokusai, Hiroshige and others in the Edo period and up to Takashi Murakami’s super-flat theory nowadays. However, “Remember Ritual (2019)” has a new origin and approach. It started with making a three-dimensional toy for my new-born baby. I had no formal art concept in mind. In the past, I was not inclined to presenting my work as moving objects in three-dimensional space. While I was making the toys, I was inspired by my own objects and started to incorporate it into my work. In the end, fortunately or unfortunately, it became an artwork and not the toy for my baby as intended. This project will change my approach to space and movement in the future.

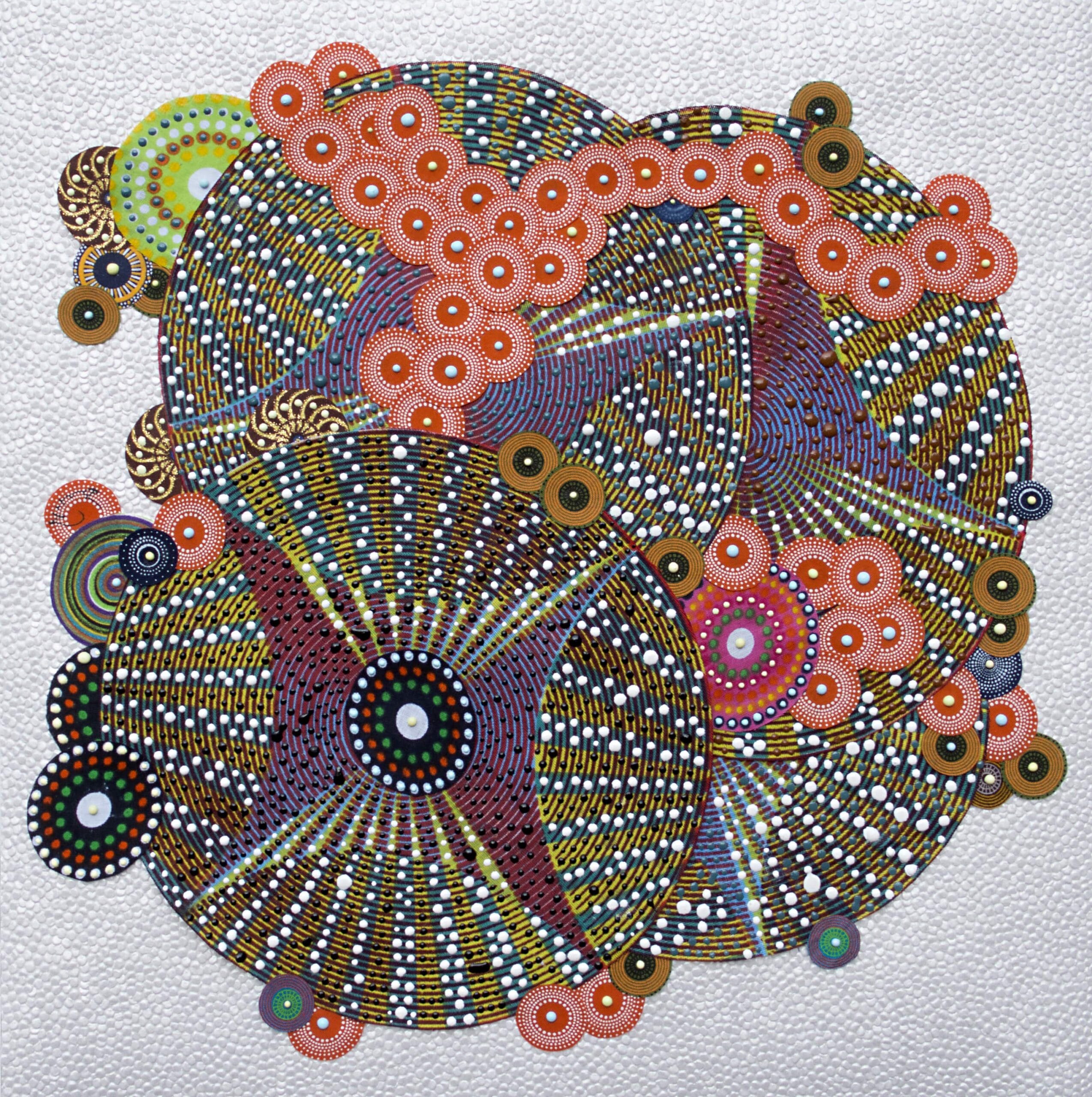

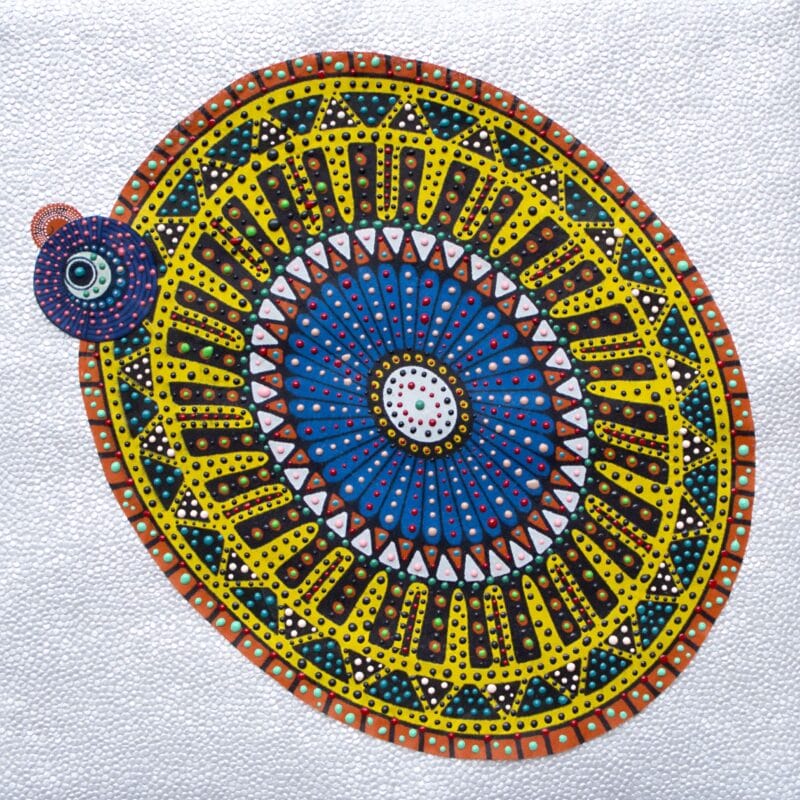

Cytokinesis 3, 2017 / fabric and acrylic on handmade paper / 41 x 41 cm / photo credit; Asuka Nirasawa

Is there a work or series of works you are particularly attached to?

All the works are like my own children. It is difficult to single works out.

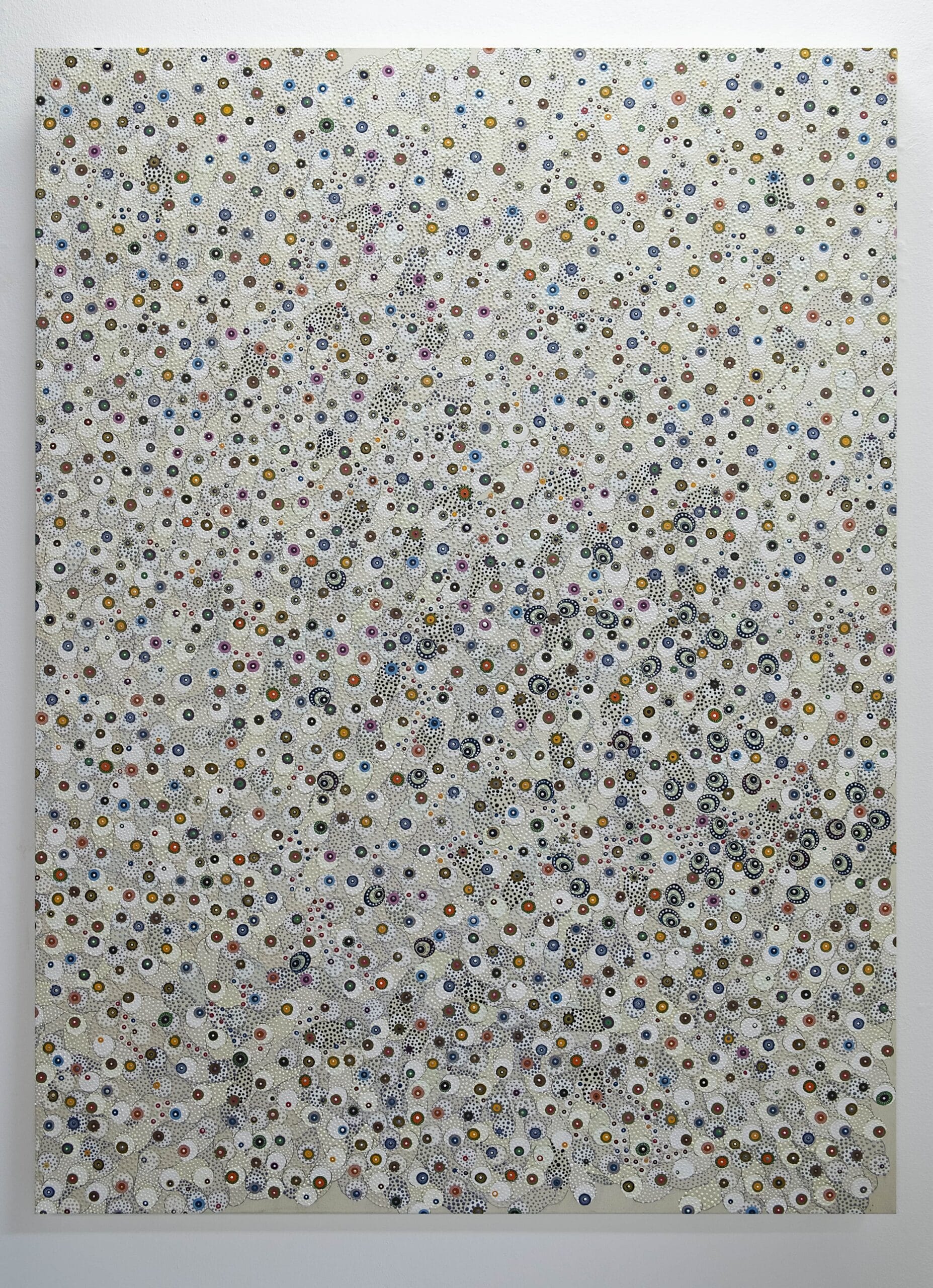

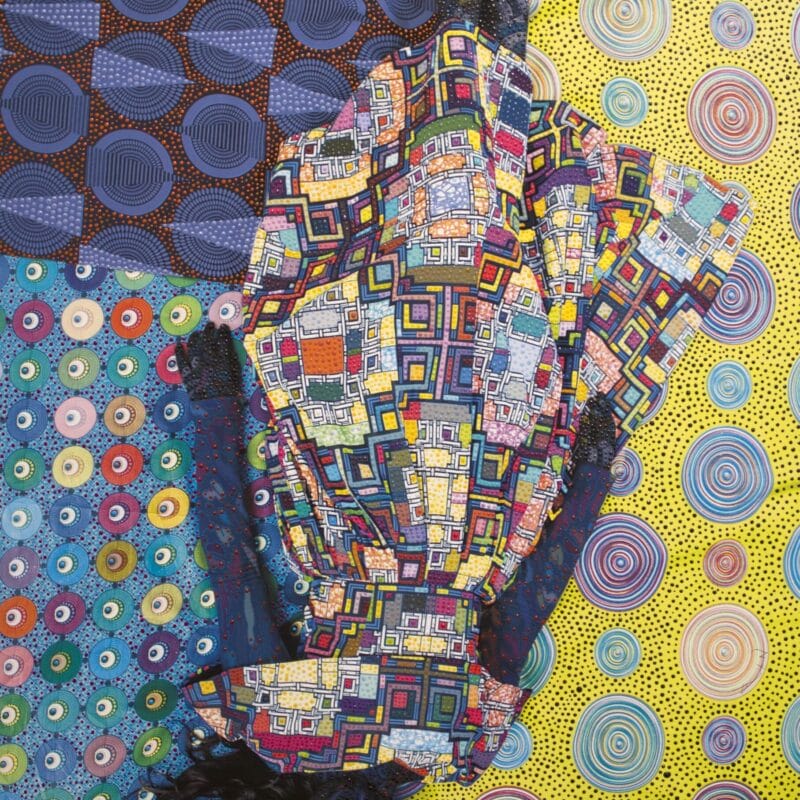

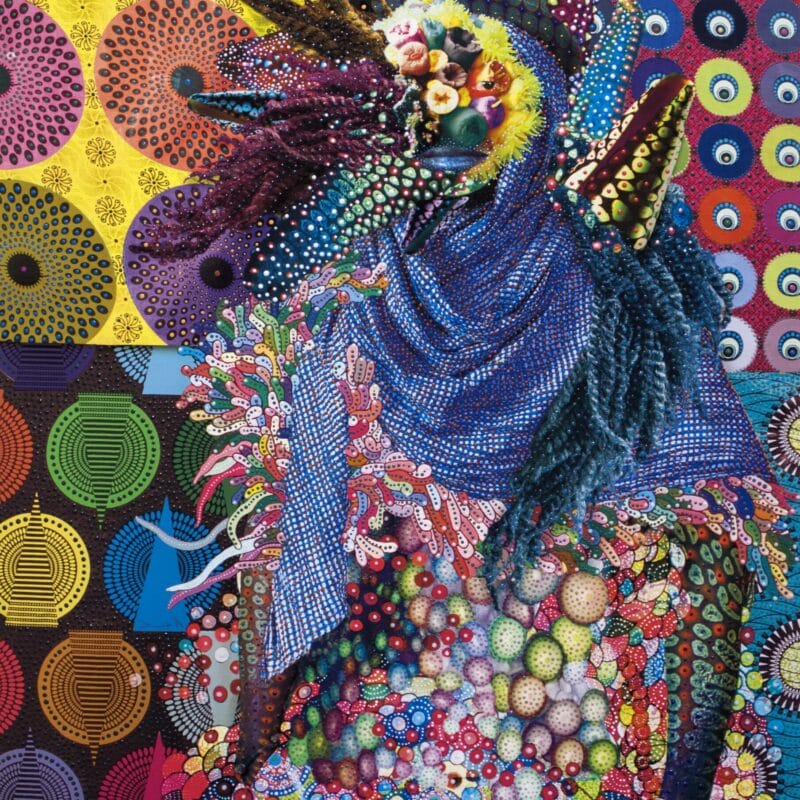

However, I try to answer with difficulty. There are two works “Cell Division” (2018) and “Remembered Ritual” (2019). The reason is that the background behind these works is completely different from that of my other works. I made these two works during my pregnancy. My pregnant body was beyond my control: I felt that the child in my womb was manipulating my body and soul. It was a very big experience for me when another existence dominated my mind and body. At that time, I produced these works as if an external force drove me. This was a shocking event for me.

Cell division, 2853 cells, 2018 / fabric, acrylic medium, glitter, pencil on canvas / 200 x 150 cm / photo credit; Asuka Nirasawa

How did the pandemic affect your work as an artist and your research?

Physically, the Pandemic affected my work and research mostly in relation to the aspects that I couldn’t go out and meet with people physically, which was uncomfortable.

The pandemic has created a variety of regulations that force people to realize that they don’t need what they thought they needed before. It cleaned out peoples’ lives and returned it to its original, sharpened, simple and fundamental situation. I think that is a good thing.

When I lived in India, I had a similar experience. It was a period of many challenges. Life was interesting but not comfortable and easy. But in it, the true meaning of life, delightfully, the existence of death/life and other fundamental questions arose, and I thoroughly sought out those questions. I remember feeling refreshed after struggling with that situation. I think the pandemic creates a similar situation, where it is easier to ask such fundamental questions to ourselves.