Interview with Tamara Kostianovsky

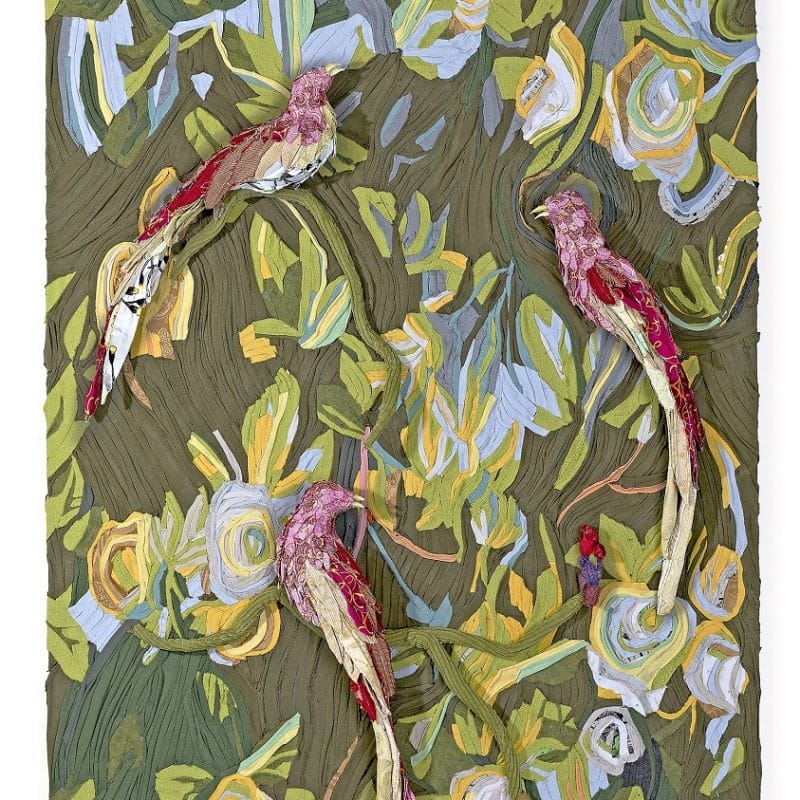

*Featured photo: Smack Mellon Installation Views, 2021. Image Credit Etienne Frossard

The work of Tamara Kostianovsky plays with the ambiguity of our perception of reality. Her meticulous works hide the vitality of beauty within the macabre form of a carcass, because nothing, perhaps, is ever as it seems and everything hides different aspects of truth. To discover the true essence of her work, as well as the world around us, it is crucial not to give in to the temptation of making do with the surface and façade of reality, but rather to observe its manifestations with attention and in depth to fully understand and experiment it.

Tamara Kostianovsky was born in Jerusalem, Israel in 1974, and grew up in Buenos Aires, Argentina. She received a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree from the National School of Fine Arts “Prilidiano Pueyrredón” in Buenos Aires and a Master of Fine Arts degree from the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, PA.

Kostianovsky is the recipient of distinguished awards including a fellowship from the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation, and grants from New York Foundation for the Arts and the Pollock-Krasner Foundation.

In the United States, her work has been exhibited at venues such as El Museo del Barrio; The Jewish Museum, Fuller Craft Museum, Urban Institute for Contemporary Art, and many others. She has presented solo and group exhibitions in Italy, France, and Argentina. Amongst many others, Kostianovsky’s artwork has been featured and reviewed in prestigious publications such as The New York Times, The Boston Globe, WBUR, The Village Voice, Marie Claire, La Repubblica, El Diario New York, Colossal, and Hyperallergic.

She lives and works in Brooklyn, New York.

Smack Mellon Installation Views, 2021. Image Credit Etienne Frossard

You use the soft and fluffy textile medium to create works with a full-bodied visual impact, as heavy as sculptures: from stumps of cut trees to large animal carcasses. How did you come to this synthesis and how does the public relate to such powerful works? Why did you choose the textile medium?

I make sculptures and installations using discarded clothing which come mostly from textiles I find in my home, like old t-shirts, kitchen rags and worn-out sweaters. I started working with this unusual material through my own experience of immigration from Argentina to the United States about 20 years ago. In fear of the winters in the East Coast, I had brought many sweaters and warm clothes which I accidentally shrunk in the drier within the first few months of living here. The shrunk clothes had memories imprinted in them and I saw them as a potential material to make art with. Over time, the use of this media became political: I wasn’t buying art supplies and was instead “upcycling” something that otherwise would end up in a landfill. Most importantly, I saw clothing as a surrogate for my body, a type of second skin. At that time, I was influenced by Feminist Art and admired to the work of women artists who used their bodies as “material”, such as Ana Mendieta, Janine Antonine, and Hanna Wilke. In my case, the inclusion of my clothes gave a performative aspect to the work.

Within a few years of being in the United States, I had cannibalized my wardrobe for the creation of naturalistic sculptures of butchered animals which spoke about violence to the female body. These works were informed by my upbringing in Buenos Aires during the Military Dictatorship, an era of state-sponsored criminality which overlapped with my own political awakening. The imagery of cows was natural, Argentina is known for being a strong exporter of cattle and one can see images of butchered cows in every market throughout the country. By transforming my clothes into sculptures of butchered cows I was including myself in the pervasive architecture of violence that seeded both Argentina’s and Latin America’s history since colonization.

Cow Turns into a Landscape, 2021. Image Credit J.C.Cancedda

Beauty and harmony are hidden in many of your works between the folds and shapes of animal carcasses hanging as in slaughterhouses. Is it an invitation to look beyond the surface of the image in contemporary society saturated and greedy of images or is it more the revealing of the dark side of reality behind the embellished surface that is shown?

I think it’s both! Particularly, it is a strategy that makes the work seem attractive to the viewer, so they can

“stomach” being in the presence of sculptural works that are visceral and somewhat repulsive.

Cow Turns into a Landscape, back, 2021. Image Credit J.C.Cancedda

You use recycled textile materials for your works where the theme of the environment is always very present. How are your works born and what are the sources of inspiration or events that initiate the process that will lead to giving shape to a work? And what do you think is the role of art and of the artist in the battle in defense of the planet?

Making artwork about wounded bodies in the era of climate change took my work into a more environmental path in recent years. I have used clothing belonging to my father, who passed away not too long ago, to make naturalistic sculptures of tree stumps which spoke about feelings of loss, of the cyclical integration of the body to landscape, and of violence to the Earth. The tree stumps are made with a palette reminiscent of human anatomy. They anthropomorphize the landscape and highlight a common materiality amongst all living things. These cut-down trees carry

a striking, violent gash, so this aspect continues to be related to my interest in the wound as a source of artistic inspiration.

Tropical Abattoir is my most recent series, which features carcasses that visually transform into vegetation and become vignettes that host birds and exotic plants. They are made from repurposed upholstery fabric, my clothes, and textiles that come from various sources. These large carcasses are exhibited suspended by the ceiling, with motors that make them spin. I think of them as a half abattoir, half fashion runway. They ask what would happen if the images of vegetation and bird life that we are all so drawn to were to come to life and overrun our world. I think of these works in terms of a metamorphosis. The concept is to transform the carcass from a site of pure carnage into a receptacle of new life that sprouts out of it—almost like a utopian environment. I don’t know that art can do more than illuminate these topics.

Tropical Abattoir, Studio Shot, 2021. Tessuto da tappezzeria usato e altri tessuti tessili, unghie finte in acrilico, catena, Motore. Photo: j.C. Cancedda

What are the other issues of contemporary society that you feel you have to face through your artistic work?

Through my artwork I have worked to understand systems of violence in Latin America. Art has helped me process the loss of loved ones. More recently, my art has opened a more hopeful line of work in which the work embraces a new optimism that comes from giving a utopian, physical form to the healing of the Earth. My work also reflects on the experience of immigration from Latin America to the United States, which gives me the opportunity to synthesizes the imagery I saw growing up in Argentina with the abundance of materials and consumer culture that came to define American culture.

Your artworks are born from a slow and painstaking work. How do you choose the material and how do you proceed from the simple piece of fabric to the finished sculptural work? What are the major technical difficulties you encounter? How many techniques do you use and how long it takes on average for a single work?

I work with fabrics I have at home, so the materials are usually items that have clothed my body, that I have washed before, that have memories imprinted on them and that are familiar to me. To begin a sculpture, I build un underlying structure with armature wire and wood, before sewing the fabric onto it. It’s a long process that takes me a few months, depending on the size of the sculpture, where a battle begins between the image I have in my mind and the materiality of what I can build with my hands.

Smack Mellon Installation Views, 2021. Image Credit Etienne Frossard

There are fundamental moments in the path of an artist: when he/she understands that he/she wants to be or become an artist, when he/she feels to have found the right way to express himself or herself and when he/she gets involved for the first time by relating to the public. Can you identify and tell me about these three moments of your career as an artist?

I knew I wanted to become an artist at a young age, my father was interested in painting and in the arts in general and took me to museums very early on. I was encouraged at home to pursue these interests.

I realized I was starting to carve my own path in art when I was a student in Philadelphia, USA, where I worked with fabric to create sculptures that were reminiscent of the human body. I made a “surgical table” with my shrunk clothes, which felt that for the first time I was making something unique that was a direct reflection of my own experience. I felt torn and displaced in the United States during my first years here and the disjointed organs on the cold, metal table expressed those feeling and ideas of alienation. The clothes were my surrogates. Also, my father was a surgeon, and I grew up seeing imagery of the open body through the photographs of his operations that were ubiquitous in our home. This “Eureka” moment coincided with the public being engaged with this point of view and that work marked the beginning of a dialogue between my practice with the outside world. My professors and classmates where excited about this project and soon after I got opportunities to exhibit my work.

Smack Mellon Installation Views, 2021. Image Credit Etienne Frossard

The next project you are working on? And a project that you would like to be able to realize instead?

I am working towards a solo exhibition at Slag Gallery in New York, which will take place in September of 2022. It’s my first solo exhibition with the gallery, in a great space, and I am planning an ambitious site-specific, kinetic installation for it. There isn’t another project I am daydreaming about for now, I tend to concentrate all my energies onto what is in front of me. I am also excited that my solo exhibition “Fibrous Landscapes” is extended in Paris at gallery Rx until mid-January.