INTERVIEW WITH MARINA GASPARINI

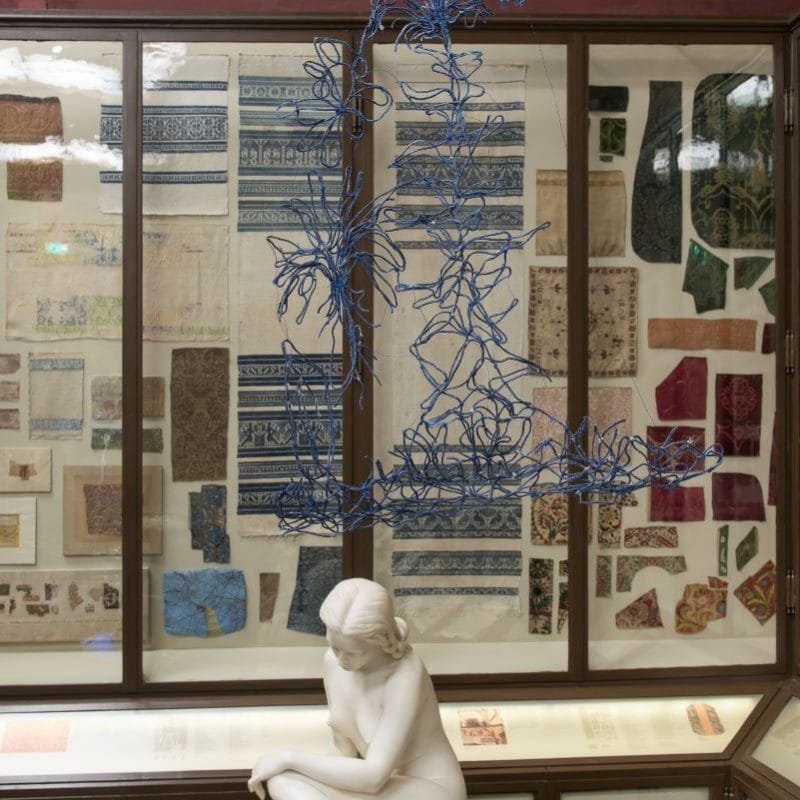

*Featured photo: Atlas X, dettaglio, 2014, 47 elementi filo di cotone, dimensioni variabili da 40×60 a 100x110cm. Il denaro è un bene comune, Modena, Galleria Civica, Sala Gandini, 2014. Teatro dei Prodigi, Palazzo Poggi, Bolo-gna 201. Photocredits Rolando Paolo Guerzoni, Modena

Translation by Marina Dlacic

It can be a mark that twists and then runs away, a floating apparition in nature, a large luminous gesture traced with small LEDs, the soft structure of a fabric without interlacing, the suture that decorates a broken ceramic; it can be in the wind, in the domestic space, clinging to historical architecture or sewn into the subdued words of a book; it can be drawing, writing, body: in Marina Gasparini’s work, thread has been a constant variable for a long time.

Born in Gabicce Mare (Pesaro and Urbino), the artist lives and works in Bologna, where she began her exhibition activity in the 1980s, and is a professor of Graphic Design at the Academy of Fine Arts.

A vast international experience played an important role in her research, which led her to know and experience different intercultural relations. In the academic field she has held workshops on the theme of cartography in art (University of Salamanca; Universitade de Lisboa; Mimar Sinan Universitesi di Istanbul, PXL Mad University in Hasselt, Belgium, Oulun Taidemuseo, Finland; Civic Art Center in Galesburg, Illinois; Rinovation Pro Art Center in Shinano-Omachi, Japan; Archive of the Children’s Artist’s Book of Merano) and has participated in artistic residency programs in Rajasthan, Japan, United States, Finland.

The use of writing and the visual emblem and the use of textile fibers are the founding elements of her research, always driven to continuous reformulations in relation to mainly site specific projects and broad cultural interests, which draw on esoteric fields, botanical, literary and scientific, but do not neglect a fascination for ethnographic traditions. Her artistic practice is mainly based on installation, and develops starting from the reformulation of iconographies from different eras and cultures in dialogue with the architectural space.

We met her at the end of the “Transiti” exhibition, a challenging exhibition project spread in various historical and landscape places of the Reggio Apennines, which for her was an experience of verifying the “strength” of her path both in terms of design and from the point of view of the strength of the materials.

The thread is a constant element in your work and has proved to be a very versatile expressive tool, both in terms of the technical experimentation and for the possibility of applying it to projects that physically interact with different spatial and environmental contexts. Your latest exhibition, a project widespread in various historical locations and in suggestive and sometimes remote natural environments, has put you to the test in particular situations.

When we think of thread, embroidery and textile works, we can instinctively associate them with the intimate sphere, with small dimensions and with obsessive attention to detail. In reality we are talking about materials that offer great design freedom even in large-scale works such as those of Ernesto Neto or Sheila Hicks, because they are flexible, economical and whose processing techniques are always open to experimentation.The thread allows you to draw in the air, the real space is its page; it is two-dimensional and three-dimensional, and like all of us, a little bit real and a little bit virtual. In the “Transits” project in the Matildeean territories of Quattro Castella, the idea of a “museum without walls” was pursued at a perfect moment to take Malraux’s prophetic concept literally. We exhibited some textile sculptures outdoors in contexts such as hermitages and parks, where surveillance was semi-non-existent. We have placed great confidence both in the works and in the visitors; it was a new experience. Francesca Baboni and Stefano Taddei advanced this widespread exhibition which consisted of five open-air installations, at a time when I was reflecting on the opportunity offered by the lockdown to start a form of archiving my work. I had also begun to think about rather extreme “archival” practices that in some cases had to do with physically dematerializing the work by compressing it, or letting it dissolve in a natural environment, perhaps documenting these destructive rituals with some direct video that can sometimes legitimately re-enter the artist’s fantasies, or practice, as in Maya Freelon’s “Art on Fire” performance.

While the project was taking shape, however, the growing concern that the works handed over to the unpredictability of meteorological and human events deteriorated, was mostly accompanied by the fear of disrespecting those beautiful natural contexts, to which the chemical substances contained in the fibers could have brought even minimal alterations. Other materials came into play such as LED lights and metal supports and images printed on PVC or aluminum, also to maintain a separation between the organic reality of the work and that of the habitat in which we were temporarily going to insert it. Surprisingly, however, the work done with fabrics and yarns proved to be very weatherproof. This can make us think about how softness and flexibility, and even fragility, don’t always have to do with weakness.

Atlas X, 2014, 47 elements of cotton thread, dimensions varying from 40×60 to 100x110cm. Money is a common good, Modena, Galleria Civica, Sala Gandini, 2014. Teatro dei Prodigi, Palazzo Poggi, Bologna 201. Photocredits Rolando Paolo Guerzoni, Modena

The references of your research are never extemporaneous, but start from a careful reading of the history and identity of the spaces and from references to a refined, often intercultural, esoteric and spiritual iconographic imagery. The figural form is often essential and evocative, it reinterprets the memory of illustrations and images taken from ancient books and from the observation of ethnographic objects. Can you tell us the genesis of some projects?

I intervened with some site-specific projects in public or historical spaces, such as museums or places full of meaning for the communities. The density of some of them may lead us to think that the work must have enormous strength to dominate the sign complexity that runs through them. I can say instead that even with courageous (sometimes ruthless) kindness it is possible to make a contribution, if not a rereading, to a space crystallized in its semantic significance. In this, of course, nothing is more suitable than the textile work. Artists such as Heidi Bucher or James Lee Byars have erased the boundaries between the body and space through the use of that fluid and infinite material which is the fabric from which our clothes are made, and of which the furniture and the walls of the houses were once covered.

With regard to this not so obvious binomial dress-habitat, the textile collection of the Galleria Civica di Modena comes to mind, where I presented an installation that was later re-proposed at the university museum of Palazzo Poggi in Bologna. The room collects an impressive quantity of textile fragments divided by periods. The curator told me that for many centuries no distinction was made between upholstery and clothing fabrics. Textures and patterns were the same, often inspired by botanical species that were also used in the dyeing of yarns.

After a phase of research on dyeing plants, I created a project for a botanical atlas in which the yarn, dyed with the color obtained from the roots, leaves or fruits, redraws the outline of the plant itself; a kind of infographic that is anything but complex and conceptually mysterious, but respectful of the motto written on the walls of the room by the nineteenth-century collector-director Luigi Alberto Gandini. The Count referred to the art of wool and silk as vehicles of wealth, prestige and civilization and so I also included in the exhibition an embroidered book representing coins and banknotes (where botanical representations have always had a prominent place) and I let the exhibition audience put their speech on the pages.To return to your question, I think you have perfectly summarized my methodology regarding the use of images. Also in this case, in fact, I have not invented shapes or figures; I simply selected them from ancient texts, illustrated with woodcuts and engravings, where we can find those perfect lines to be transported on any support, from vector to tapestry. After identifying the key images of the project, always ready-made, the manual process is long and laborious, almost a space-time short-circuit where, through manual care, an image that is trivially diffused through the serial medium is reproduced, even if not always of so accessible reading or immediate understanding.

Schiapparelli, 2018/2021, 19 elementi, dimensioni variabili, da 7 cm a 35 cm. altezza, diametro da 9 a 36 cm. Terracotta e filo di cotone. Episteme, 2021 Museo Temporaneo del Navile, Bologna

Technical experimentation leads you to spatialize the thread, transforming the linear essence of the sign into a drawing and then, as in the last vases of red thread, into a plastic volume.

When a medium is favored, but in particular this medium, it is difficult to resist a certain metalinguism, and technical experimentation can take control over the evolution of the work. My journey with fabrics began with two-dimensionality, printing images and texts on transparent organza or fine linen for embroidery. I reconstructed the houses I lived in 3D and virtually retraced them. The frames were passed to the home printer and then I would embroider on them phrases about micro-episodes or emotions of the day. For an exhibition at the Corraini Gallery in Mantua, we reproduced my kitchen on four large fabric panels that recreated that environment in a 1: 1 format. Later I kept the real dimensions of the objects, but I decided to base the spatial representation only on the contour line, obtained with thread. At the same time neutral and organic, a particular “algodon” that I found in Madrid allowed me to experiment with the first of what I call “textile designs”. It was decomposable into threads of different thicknesses with which it was possible to obtain a very sensitive outline, which in some cases is all that is needed to make a drawing more three-dimensional. More than seeking the three-dimensionality of the design, however, perhaps I have always tried to make space two-dimensional. I initially chose to represent rocaille furniture from a style manual that made me dream of stately domestic scenarios when I was a teenager. They are resistant works that nevertheless give a strong impression of precariousness and nomadism; this is perhaps the characteristic that makes them sculptural. Sculpture, as the Greek myth teaches us, is the materialization of the drawing, indeed, of the outline of the shadow of reality. I believe that the fascination of three-dimensional rendering can be linked to the sensuality of the soft material, but also to the sublime humor that we find in the soft sculptures of Oldenburg, for example. However, I never sought the “all-round” effect except in the creation of a huge spider web that was actually a map of a Midwestern town where I was residing. The thread of the cobweb comes out directly from the belly of the “aragna”. I find that what is most exciting about textile-art is the do-it-yourself aspect, but that it is very difficult to master. In more recent works like the one you mentioned, I have used sewing thread to create a foreign and at the same time domestic texture on objects of rudimentary terracotta. The result is a kind of suit / armor that could even have a life of its own, but I would return to this work in the next question.

Ceramics have also been an interesting field of experimentation for you, in the context of an attention to the artefact that is constant and particularly sensitive in your research. How do you relate to the craftsmanship of doing?

To tell the truth, I don’t have craft skills worthy of the name. I have some basic “skills”, and I am more passionate about the history of visual communication than that of applied arts. As a teacher, I see creative young people very attracted to the new forms of digital craftsmanship, which allows them to self-produce their graphic, fashion or product design projects. Their approach is also supported by a theoretical vision. Certainly the revolutionary insight that emanates from the texts of Sennet and De Certeau is still functional, but I find that the sensitivity of the new generations towards environmental issues and the eco-sustainability of materials and processes is an even more important phenomenon. I think this is not a simple trend, but an authentic predisposition that gives hope for a future generation (including artists) careful not to create controversial works and products from the point of view of environmental impact.

However, the craftsmanship does not yet offer all the guarantees from this standpoint. But we are invested by a strong and direct message in the face of the artisan practice of reuse inherent in the work of El Anatsui, as it communicates an identity principle rather than an aesthetic one. In the same way, the textile and costume jewelery junk that Rina Banerjree expertly assembles, captures our fascination as if it were a cathartic ritual.

I also find the performative and gestural memory that the work brings with it to be important, since we can trace the birth of textile-art back to a historical moment of rebellion and the use of craft techniques such as tricot, embroidery and tailoring in a provocative and political way.

As for my experience with ceramics, in 2009, from contact with an association of artisans from the Faenza area, I started a small production of unique pieces in which I inserted thread, studs and phrases embroidered on the porcelain. They were no longer artistic and not yet design objects, or vice versa; I would use the simple and convenient definition of “artist’s ceramic”. Later I developed more expertise on what I could do with porcelain, given its ability to take on thin thicknesses like fabrics, and I referred to two talented and patient artisans from Nove, for the execution on the lathe and for the firing, but I have never departed from everyday objects.The group of vases you refer to in the previous question, on the other hand, I made them among a family of artisans from Rajasthan, and then I sewed and braided it by myself. In this case there was a U-turn and the function of the object was completely questioned by the thread that covers the elements inside them as well. What remains is the ontology of the vase, and its manufacture, in this case subject to a chain of references that involve and agglomerate materials, places, shapes and colors which, as usual, refer to a visual emblem not of my invention. Once again, I have “embroidered on it”.