Interview with Amy Meissner

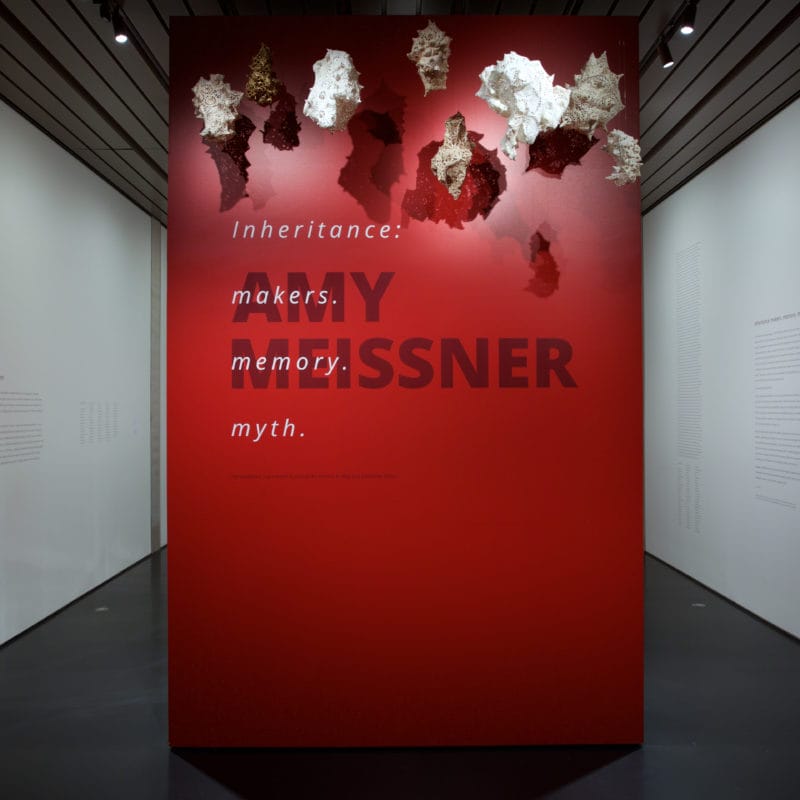

Anchorage Alaska artist, Amy Meissner, combines traditional handwork, found objects and abandoned textiles to reference the literal, physical and emotional work of women. She has shown internationally, with textile work in the permanent collection of the Anchorage Museum, the Contemporary Art Bank of Alaska and the Alaska Humanities Forum as well as many private collections. Her solo exhibition Inheritance: makers. memory. myth. debuted at the Anchorage Museum in May 2018, then traveled to the Alaska State Museum in Juneau in 2019. Her background is in clothing design, illustration and creative writing.

Artist website:

Amy, why is your choice of art aimed precisely at textiles as an expressive medium?

Can you tell us something about your history as an artist?

I was taught to embroider, sew and crochet at a very young age. As a teenager I made most of my clothes and worked in the clothing industry between the ages of 17 – 30, mostly in 2 small ateliers making custom wedding gowns. I also worked in two small factories doing everything from production cutting to sample sewing to pattern making.

In undergraduate school I studied drawing and painting, skills that easily transferred into the design career I had with clothing and textiles. In my 30’s I left the clothing industry to pursue other art-related interests in the publishing industry, received an MFA in creative writing, then had a family. It wasn’t until I had small children that I chose to return to textile- and craft-based work. It felt very natural to do this work with them at my feet, and became an opportunity to connect with the histories of Scandinavian women in my family, many of whom had passed away without my ever knowing them.

Among your textile works, which one is the one that represents you most and to which you feel most attached?

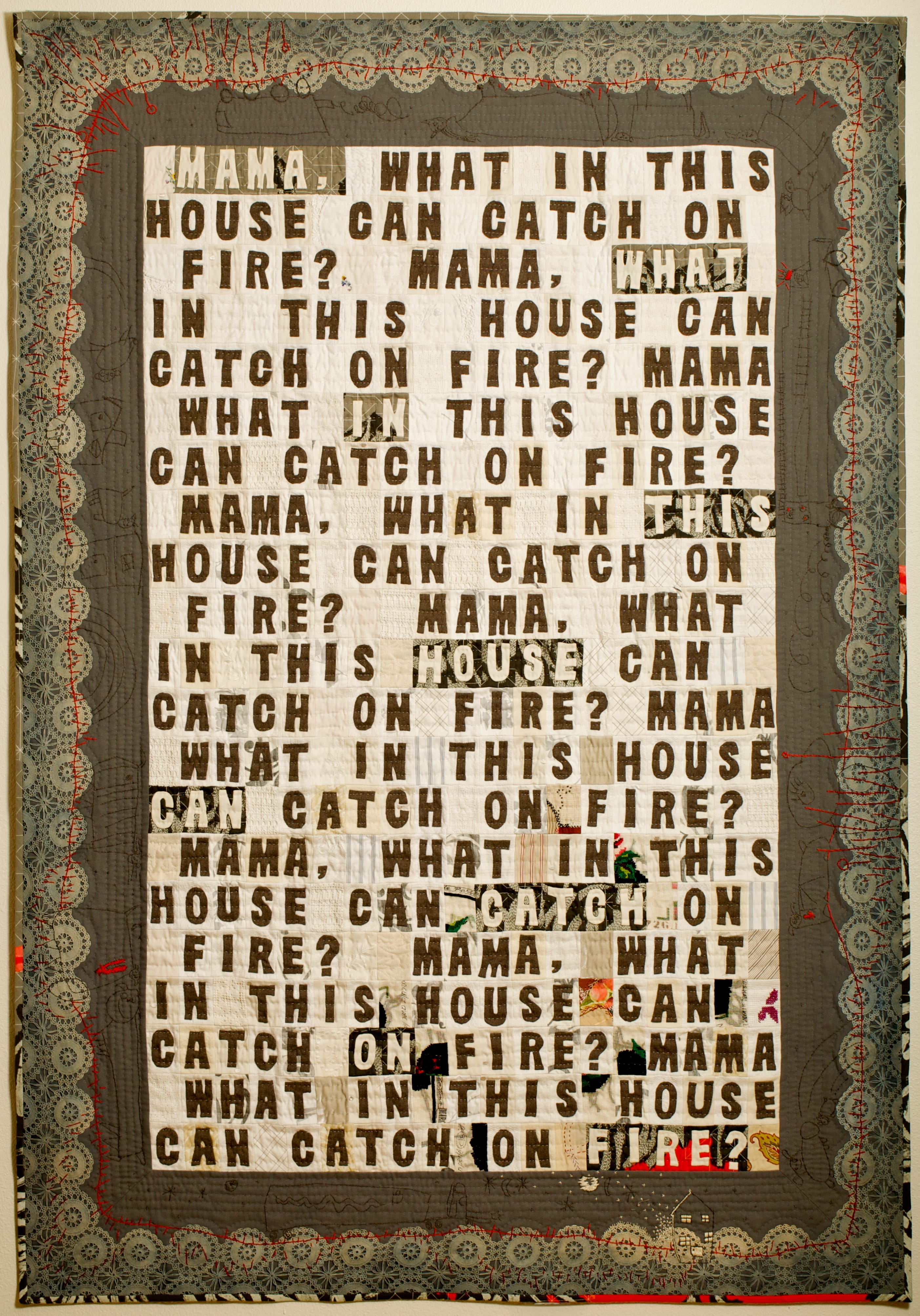

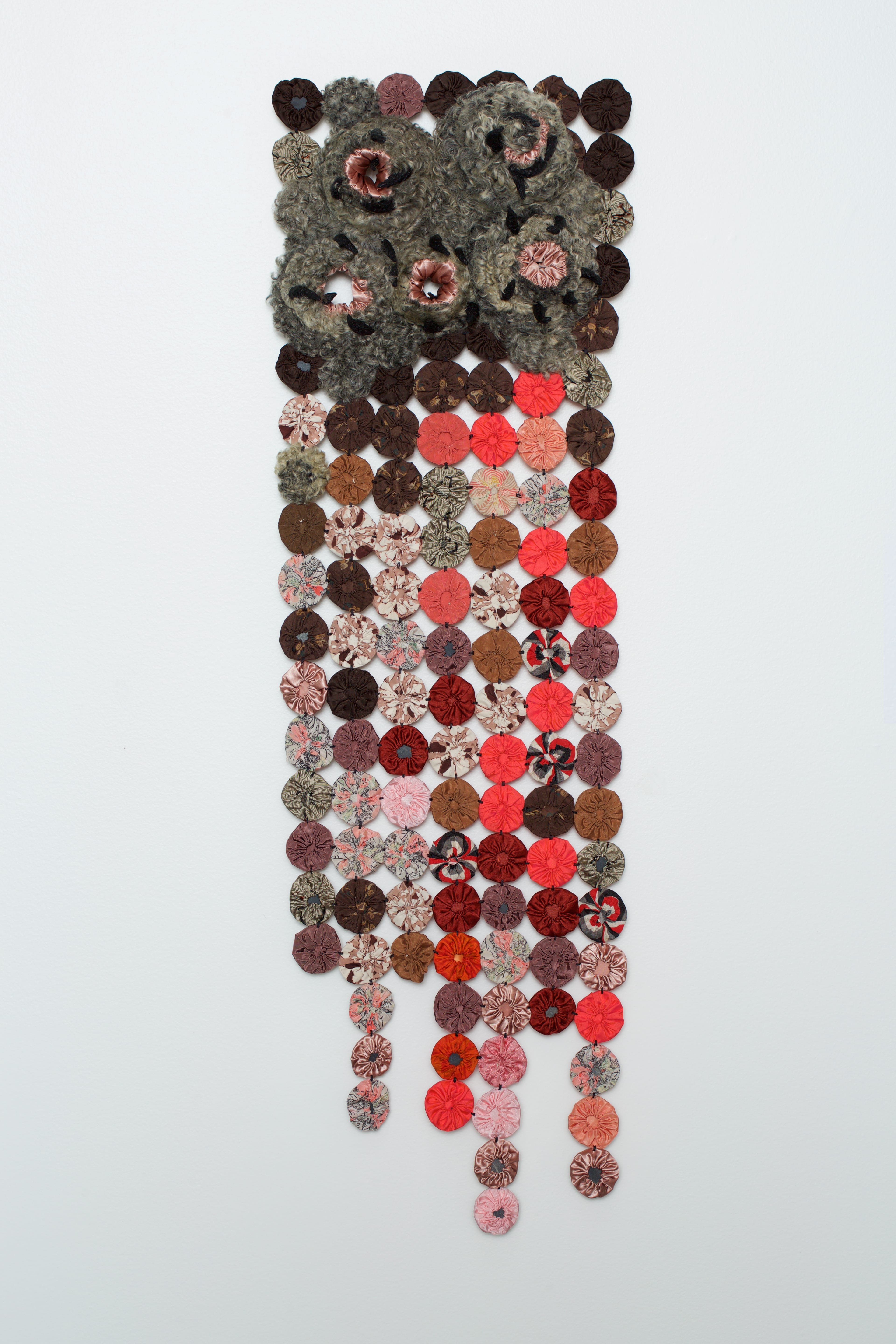

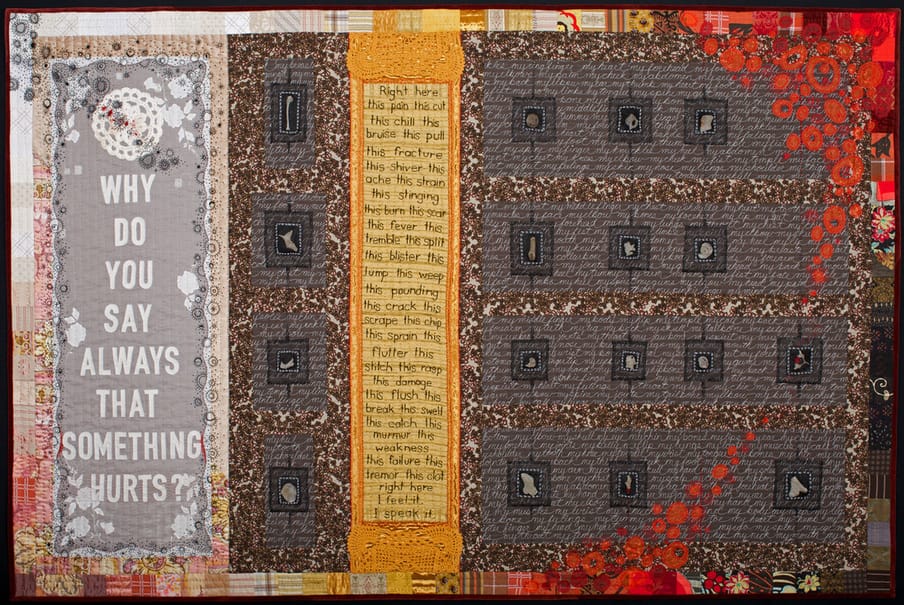

I feel most attached to “Fatigue Threshold” and “Spontaneous Combustion,” the latter of which is in the permanent collection at the Anchorage Museum. Both of these works directly address the emotional labor of women and motherhood, and are made primarily from abandoned domestic textiles — quilts, decorative embroideries, crochet work — all women-made decorative arts deemed valueless in the larger realm of art and craft, often discarded by people who can no longer store them. Both pieces reference the quilt form, featuring hand embroidery and hand quilting. Both employ repeated text that can be seen both as a litanous monotony echoing the drudgery of household and motherhood; the repetition within each piece creates a dark, manic undertone that contrasts with the original intent of the materials, which was to create beauty within the home.

Can you tell us about the “Vein Series”?

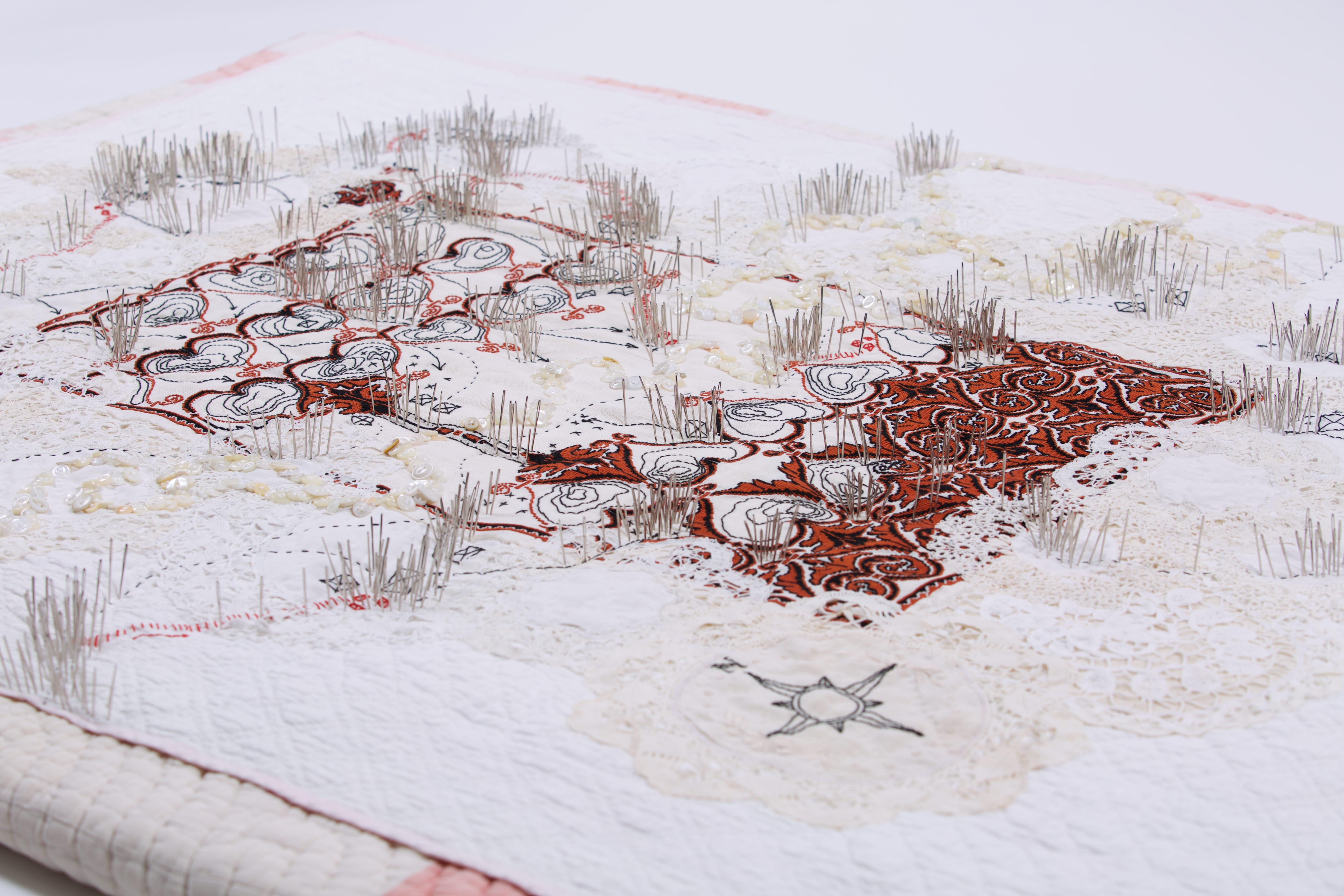

This is a small series that arose while considering the body as metaphor for landscape. I live in Alaska and my family cleans marine trash from remote beaches in Prince William Sound every summer. This is strictly volunteer, 2 adults and 2 kids with a small boat. It’s quiet, meditative work that feels overwhelming and thankless, but during the long hours gathering plastic detritus and ghost nets I have a lot of time to think. The shores also offer incredible discoveries from the natural world — different beaches have very different stones, even if they are on the same coastline. Some look like fingers, some like smooth black coins, others are cobblestones the size of grapefruit, and I never take a stone from a beach unless I’ve cleaned it first, so it feels like a reciprocity, a gift. The development of the Vein Series arose when considering how to combine found objects with textiles while referencing the body and the things we can’t control. It’s a meditation on pain and outside forces that involuntarily shape us.

Improvisation, randomness, experimentation, study, rules, design. Which of these aspects has an essential or prevailing role in the process of the birth of your work?

From this list, I’m most drawn to study and experimentation. I read a lot: women’s issues, craft thoery, motherhood, memoir, and appreciate a beautifully written long form essay. I’m introverted and very curious about other people’s creative process and inner lives. Because I have a long history of mentorship and technique- and/or skill-based work from years spent in the clothing industry, I have a very solid foundation, and therefore a springboard for experimentation with form.

In your opinion, is the technique or the idea more important? What do you think determines the success of an artwork?

I think this is where the lines between craft and art converge for me, as both are equally important for my work. Craft is skill-based and technique-oriented, and because of my history with these materials, working for 12 years in an industry that demanded beauty and perfection (especially those 9 years making wedding gowns), and along with the way I was literally trained, technique will always be important to me, but I make choices about where perfection lies, balancing it with chaotic elements so it tends to disappear into the background. For me, technique becomes the ground for the larger ideas that defines my art and the themes I keep returning to. As an artist who employs a craft-based medium, I think a lot about form and the kind of expectation and experience viewers bring with regards to materials. I primarily use older, abandoned textiles, and consider the act of remaking as an opportunity to layer narrative, and approach each work with an intention that pushes through and against the decorative arts and traditional women’s handwork.

Amy, how was “Inheritance Project” born and what is it?

The Inheritance Project began in 2015 when a woman sent me a box filled with old, hand crafted cloth “to deconstruct” any way I liked. I come from a family of generous and prolific Scandinavian needle women who sent me their handwork throughout my life, but this stranger’s act became the catalyst for a multi-year effort to collect unused, unfinished or unwanted vintage linens. despite asking contributors for histories associated with the cloth, the majority of makers, origins and timelines still remains unknown. In the spirit of generosity and a resulting catharsis for many, over 70 contributors sent nearly 650 objects, with known origins representing 20 countries and 25 states. The rigorous process of corresponding, documenting and considering each piece of unrestricted cloth informed a body of work and became the raw material for a solo exhibition that debuted at the Anchorage Museum the summer of 2018, then traveled to the Alaska State Museum in Juneau in the Winter of 2019. Through museum programming during this time, I shared this cloth for embroidery projects with children, the elderly and other women and men who were interested in the process of reclaiming or relearning a craft-based act. We embroidered, re-monogrammed and mended, all in the spirit of mark-making and re-energizing discarded pieces of cloth created by unknown women. The act of using our voices with needle and thread gave these unknown women a voice.

These salvaged embroideries, linens and crocheted items embodied the original makers’ intentions for beauty, home and possibility. Difficult to discard, but burdensome to store, this cloth was saved for grandchildren, saved for someday, with the very best saved for never. Cutting such material apart and reconfiguring it for a contemporary context meant sifting through the tangible and intangible detritus of women’s lives. Some of it spoke long after its solitary makers no longer could.

My work with needle explores this literal, physical and emotional work of women — gathering the collective murmur in women’s handwork and combining it with my own to generate a new mythology. I approach this textile work with traditional skills and time, confronting an expectation of beauty with a raw female gaze. The resulting narrative does more to reveal an emotional truth about a life than any partial or assumed history. Completing a story feels human, crafting by hand even more so.

Despite conflicted emotions around inherited objects, ideals and perceptions, we continue this potent ritual of insisting what we create has value, even if useless, unwanted, outdated — even if conjured from scraps of a life.

What does the “embroidery gesture” mean to you, which I believe plays an essential role in your works?

I’m the twelfth first-born daughter to a first-born daughter, a lineage that reaches back to 1640’s Sweden. I know all of these women were taught hand skills and maintained a material intelligence with their objects and surroundings. I was taught many of these same skills by my Swedish mother as part of a whole and complete home life, before even starting school, so embroidery feels fundamental to who I am even though it was a dormant skill for many years when I was engaged in other pursuits.Embroidery for me is mark making and a way of holding an inner chaos that pushes back against contemporary domesticity. I don’t embroider to embellish my home in the way the women in my family did, I embroider to make sense of my emotions. It’s less about decoration and more about the physicality of the gesture.

What are you working on right now?

I’m engaged in a body of work around birth and motherhood, both topics that feel overlooked and devalued in literature and the arts. Women’s brains are literally and permanently altered after the wash of hormones related to pregnancy, birth, and/orcaretaking during early childhood, but this is barely recognized or even studied, let alone revered despite the fact that such a biological change has kept our offspring — humanity, really — alive for centuries. We’re more empathetic, spontaneous, assertive and better able to multitask after such a brain change, but we don’t call this “intelligence,” if anything, we denigrate these qualities and refer to “mommy brains,” something base and reduced. Are we distracted? Yes. Sometimes angry? Yes. Not the person we once were? Of course not, and this is a frightening prospect. SoI’m in the process of probing this landscape, creating work that peels back contemporary motherhood to reveal something primal, raw and ancient through the use of vintage domestic/household linens and traditional techniques.