Jean Lurςat

Translation by Marina Dlacic

Jean Lurçat is considered the father of modern tapestry, renovator of French tapestry and prolific producer of tapestry cardboard. He leaves a huge amount of woven works and has had the merit of enhancing the art of tapestry thus inspiring the production of other artists who began to use it as their own means of expression. The interest in this art was a belated revelation. In fact the young Lurçat initially engaged in medical studies, then abandoned them to turn to artistic studies and more precisely to painting.

Jean Lurçat was born in France in 1892 and, thanks to the artist Victor Prouvé, he attended the so-called Nancy School; this allows him to begin to structure his own artistic language that he will put into practice when, in 1912, he moved to Paris to the Academy of Fine Arts and later to the prestigious Colarossi Academy.

The artistic panorama of the period was very rich in stimuli and well reflected the socio-political context of the early decades of the 1900s. In the art salons, the painter met and made friends with the likes of Matisse, Renoir and the poet Rainer Maria Rilke. Lurçat’s work is strongly influenced by Cubism, Dadaism and Surrealism, through recurring motifs such as nature, animals and the cosmos. He manages to combine characteristics of the various artistic currents without ever being completely conditioned by them; the result were works of clear cubist inspiration, capable of including a wide range of aesthetic values of the early and mid-twentieth century. With the passage of time, the artist’s interest in the applied arts and the talent implemented by artisans becomes increasingly clear; in 1917 he exhibited his first tapestries, Filles Vertes and Soirée dans Grenade.

After World War I, Lurçat arrives at a more mature style that manages to reconcile the characteristics of religious-themed tapestries with modern forms of abstraction, real elements coexist with fantastic representations of vegetation and animals, making the whole extremely decorative.

Lurçat begins to travel incessantly, called by many due to the artistic value of his works, and the journey becomes a fundamental element for the artistic growth of the French artist who is commissioned tapestries in many of his destinations, he will be one of the first artists of Western Europe to exhibit in the Soviet Union.The success and the spread of his tapestries convinced the artist to completely abandon painting to devote himself completely to textile art. His mind begins to conceive an ambitious project: to revive the ancient French Manufactures to give new luster to the ancient art of weaving. The interest in tapestries becomes a real professional activity that takes advantage of the collaboration of the textile factories of Beauvais. Following the bombings, the textile machines operating in Beauvais were transferred to the Gobelins Manufacture with which the artist collaborated for the production of many of his works. In fact, it was precisely the Gobelins factory that wove, in 1936, the first official commission with the title Les illusion d’Icare.

Les illusions d’Icare (fondation-lurcat.fr)

During the German occupation, he retired to the south of France engaging in the creation of huge tapestries that represent the spirit and drama of the historical context.

L’Apollinaire, dettaglio (fondation-lurcat.fr)

In 1957 he launched a series of monumental tapestries, Chant du monde, ten tapestries representing a 20th century Apocalypse. Needless to say, the inspiration for this series comes directly from the tapestries of the Apocalypse, dating back to the fourteenth century and exhibited in Angers in France.

In Angers there is also the Jean Lurçat museum which is housed in the old Saint-Jean hospital. Since 1968, the masterpiece series by the French artist has been exhibited in the sick room. Modern replica of the medieval series, the cloths were woven from 1957 and 1966 in Aubusson but, due to the death of the painter, the series remained unfinished with the weaving of eight instead of ten tapestries.

The medieval tapestry series was not only important as a model for Lurçat’s tapestries, it contributed to a profound reflection that led the artist to define the space in which the modern tapestry would move. In the opening statement of his book “Designing Tapestry”, Lurçat talks about tapestries as an art tool conceived and designed to always be connected to architecture.One of the themes most dealt with in the book is the manufacturing process, that is the transition from cardboard to weaving. It is unthinkable that the interpretation of the tapestry maker can, in some way, distort the idea of the cartonist. For this reason, Lurçat insists on the need to establish a non-interpretative code that would facilitate the work of artists. But the fundamental mistake was to model a tapestry using a painting not intended for such use as cardboard. For Lurcat this was a highly misleading and disrespectful method of both works of art.

In 1939 he settled in Aubusson and immediately put into practice his reflections on the making of stained cloths. The color palette is simplified and the non-interpretative code, so dear to the artist, takes shape in the cardboard. We talk in fact of the coded cardboard, a black and white cardboard showing the numbers corresponding to the colors.

In 1945, Lurcat moved to Saint-Céré, where he bought and restored a ruined castle to set up his personal atelier. To date, the castle of Saint-Laurent-les-Tours houses a museum open to the public.

Lurcat died in 1966, in the 1980s, the widow founded the Musée Jean Lurcat de Saint-Laurent les Tours and the Musée Jean Lurcat et de la Tapisserie contemporaine to which she donated numerous works.

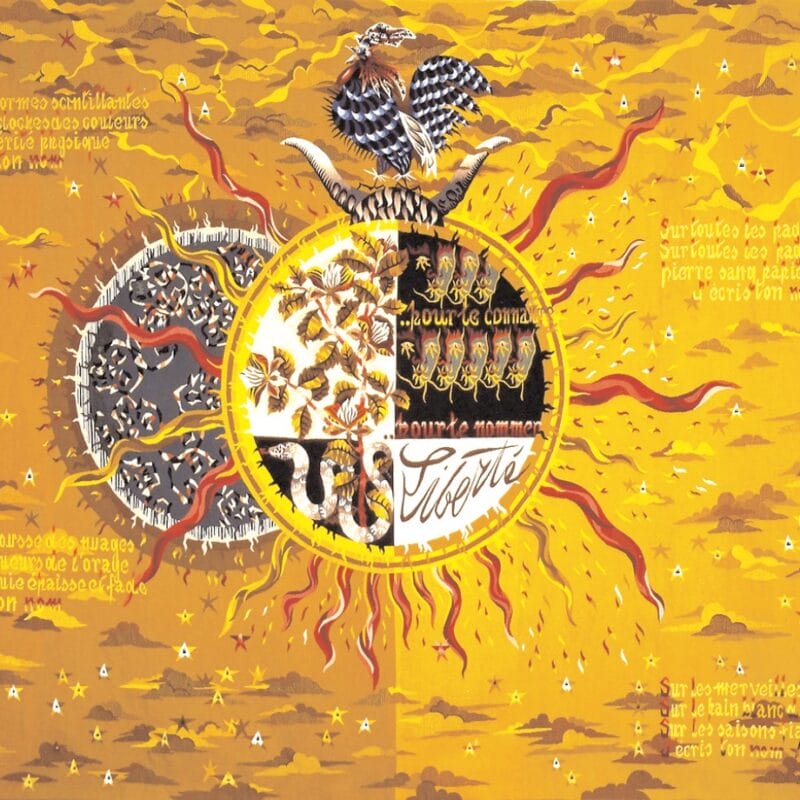

Le zodiaque blanc (boccara.com)

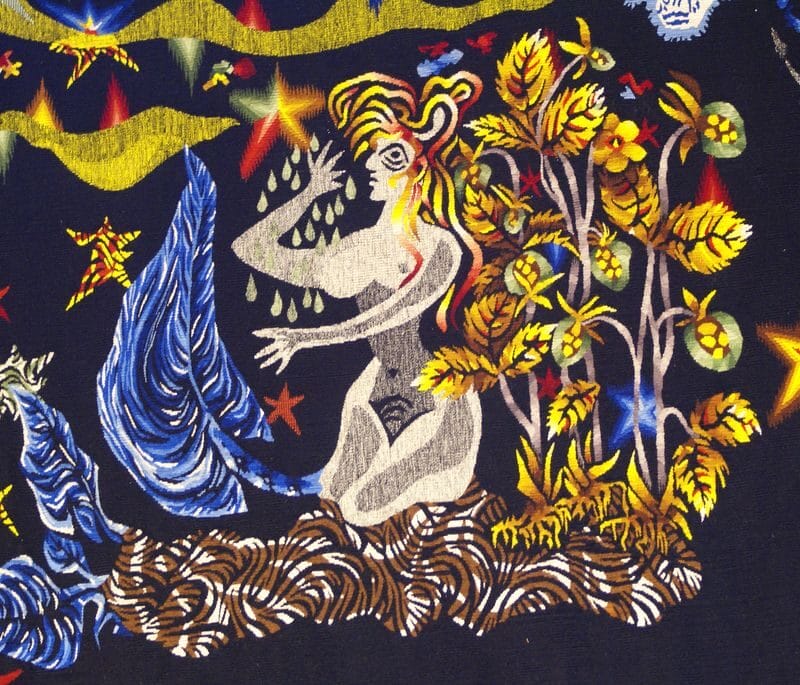

L’eau et la nuit (christies.com)