LEONARDO BENZANT

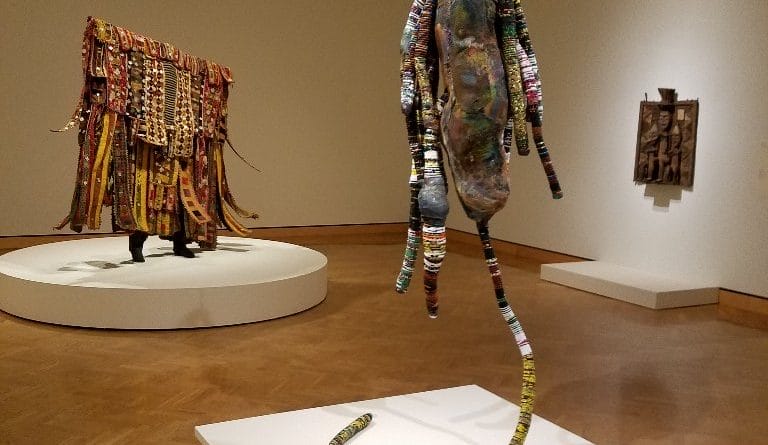

*Featured photo: MIA Install: Radiations Of The Midnight Walker, Victorious In Round Number 8, He Who Moves Inside Of The Womb Of Magik And Timelessness, He Who Moves Here, There, And Everywhere Chanting: I AM THE GREATEST! And Chanting: WITCHCRAFT WILL NEVER TOUCH ME!, 2016. Materiali: manichino, stoffa, vestiti, mpolos (parola kikongo per polvere o polveri), spago, macinacaffè, vija (ashiote), polvere di carbone, efun (polvere di guscio d’uovo) , cenere di sigaro, glitter, acrilico, inchiostri acrilici, medium gel, corda, cuoio, monofilamento, perline di vetro e vari. Dimensioni: 120″ X 21″ X 24″ (circa)

Leonardo Benzant is a mixed media Dominican-American artist with Haitian heritage, born and raised in Brooklyn. His artistic practice is informed by his studies and the Kongo and Yoruba initiation rituals: a spirituality that shapes his art and that the artist reinforces through constant research in the religious, artistic, historical and cultural realms, up to the deepening of African and Caribbean rituals, maintaining a continuous dialogue with modern and contemporary art. In constant experimentation with a wide variety of materials and techniques, Benzant creates complex sculptures and dynamic installations in which he uses everything from objects trouvés to beads.

Benzant received a Joan Mitchell Foundation Painters and Sculptors Fellowship and attended the Pratt Institute and the Galveston Artist Residency in Texas. His work has been shown in exhibitions at the MoAD Museum of African Diaspora in California, the Museum of Arts and Design in New York, and the King Juan Carlos of Spain Center at New York University. He has participated in Untitled in Miami Beach (2019 and 2020), Expo Chicago and Pulse Contemporary Art Fair.

His work is part of several important private and public collections, including the Weisman Museum, the Minneapolis Institute of Art, Bunker Artspace and the Harvey B. Gantt Center for African American Arts + Culture in Charlotte, North Carolina.

We interviewed him on the occasion of his recent solo exhibition at Claire Oliver Gallery in Harlem, which closed in January 2022.

Who is Leonardo Benzant?

I began describing myself as an “urban shaman” about 20 years ago. It was a way for me to transform my past and the direction I was going, which was very self-destructive. I grew up in Bushwick, a rough neighborhood in the crack era of the 1980’s. This means that I was a child in an environment with an incredible amount of violence and drug abuse. I am a child of hip hop, house music and dancehall reggae. Also, I had immersed myself in listening to jazz, studying it’s philosophies and saw it’s principles as being linked to African languages, aesthetic and cosmology. I had observed African Diasporic and aesthetic principles including: improvisation, polyrhythm, call and response, intuition, and oral history. These elements express themselves, in various forms, in the materiality of my work. I create structures that reflect multiple patterns and chance-operations that suggest the influence of spiritual forces behind the work and its ideas.

My mother in an attempt to help combat the negative influences of my neighborhood put me in Catholic school, but I felt such a disconnection to that. Although I could not fully articulate it at the time, on an instinctive level, I associated it with what I now understand as the ways in which our people in the Black Atlantic have been colonized. Although, intellectually and academically there has been much progress and discussion about decoloniality so little attention has been given to the foundations of African philosophy and cosmology which come from the relationship our people have with the earth, the rituals it inspires, magic and spirituality. In a sense, it is still the last stone left unturned because intellectuals not being initiated usually can only scratch the surface. The singularity and poignancy in my work involes delving deeper into this realm. Often the west has painted a picture of African spirituality as primitive, evil and backwards. Regarding the rituals of the African diaspora and the complex nature it’s belief systems, nothing could be further from the truth.

What does it mean to you to be an artist?

As a boy I loved to sit at the window to witness the world of my old neighborhood with all of its drama, trauma, violence, beauty, and poesy. I became an artist in my head, long before I picked up a pencil, needle or brush. The artistic sensibility came first. It’s the origin of becoming an artist. It’s the curiosity and learning to see things that comes before actually making a mark. The unique way of seeing becomes your artistic vision.

Being an artist is an invitation from the unknown and from the unlived aspects and dimensions of your soul that create an unrelenting and formidable inner necessity, desire and curiosity to both understand your world, who you are, and your place in your world. The invitation forces you to seek ways to find or create language in terms of your own plasticity, aesthetic, materiality and sensibility. I have always felt as though my purpose as an artistic channel was to give birth to something new, magical, and singular: a new world, a new universe, a new visual vocabulary that is personal and has roots in both ancestral and experiential knowledge.

Being an artist gives me a way to excavate all the different parts of who I am: my Afro Dominican/ Hatian roots, my gender, being a son, brother, father, priest and lover. It also allows me to synthesize my years of looking at other artworks in museums, galleries and books. The MET for example gave me access to global and ancient cultures. I see myself as part of a continuum. Being an artist also saved my life. I was on a very destructive path. It gave me a sense of purpose and gave me a reason to cultivate discipline in my life. I see being an artist as a hero’s journey. One has to develop a warrior spirit to face the tremendous negative messages that we receive around us, but most importantly to overcome the fear inside of yourself.

Your works are the result of painstaking work that requires slowness, concentration and patience. Is there also a ritual and spiritual dimension in these gestures?

There exists a subjectivity around notions of time that are both personal and cultural. Our Western notions of time are cultural constructions that have been imposed on other cultures for the purposes of standardization. We take our current Western-based notions of time for granted, not remembering that other cultures have had and in some ways still have their own time constructs. The need for global synchronization of time is rooted in a European desire for expansion and domination. The Western project of standardizing ways of marking time were in large part a project that involved efficiency in moving products.

I think of the slow process of my work as an invitation to remember that our sense of time is largely a product of the imagination. What’s fascinating about the slowness of my process is that my work tends to move counter to this ideological position of efficiency. My process takes time. It takes the time it needs to take because it’s not about efficiency. It’s about the process, it’s about the ritual. My godfather, who initiated me into the Kongo-derived ritual complex known as Mayombe once said, “nature doesn’t rush for no one”. From a Kongo perspective, nature is alive, is animate, nature is where we get mpungo, nkisi, malongo, bilongo-all forms of medicine and spirit.

Slowness implies a meditative passage of time and is counter to an industrial society and a machine-like art world where everything is moving so fast and according to the latest trend. Slowing down gives us access to deeper reflection in the process of making and also heightens the sensations that are visual and tactile. Slowing down allows for a concentration and attention to structures that evolve over a period of many months. The journey is more like a marathon than a sprint and involves my whole being: physically, emotionally, mentally and spiritually. When working I am immersed in the world of the work and I can lose my sense of time. There is joy and timelessness, but also a peculiar loneliness that requires a firm sense of composure and tenacity we might call patience. My work and process also requires courage and vulnerability to embark into the unknown, daringly holding space for those unique visions we each hold inside and are at times tempted to reject.

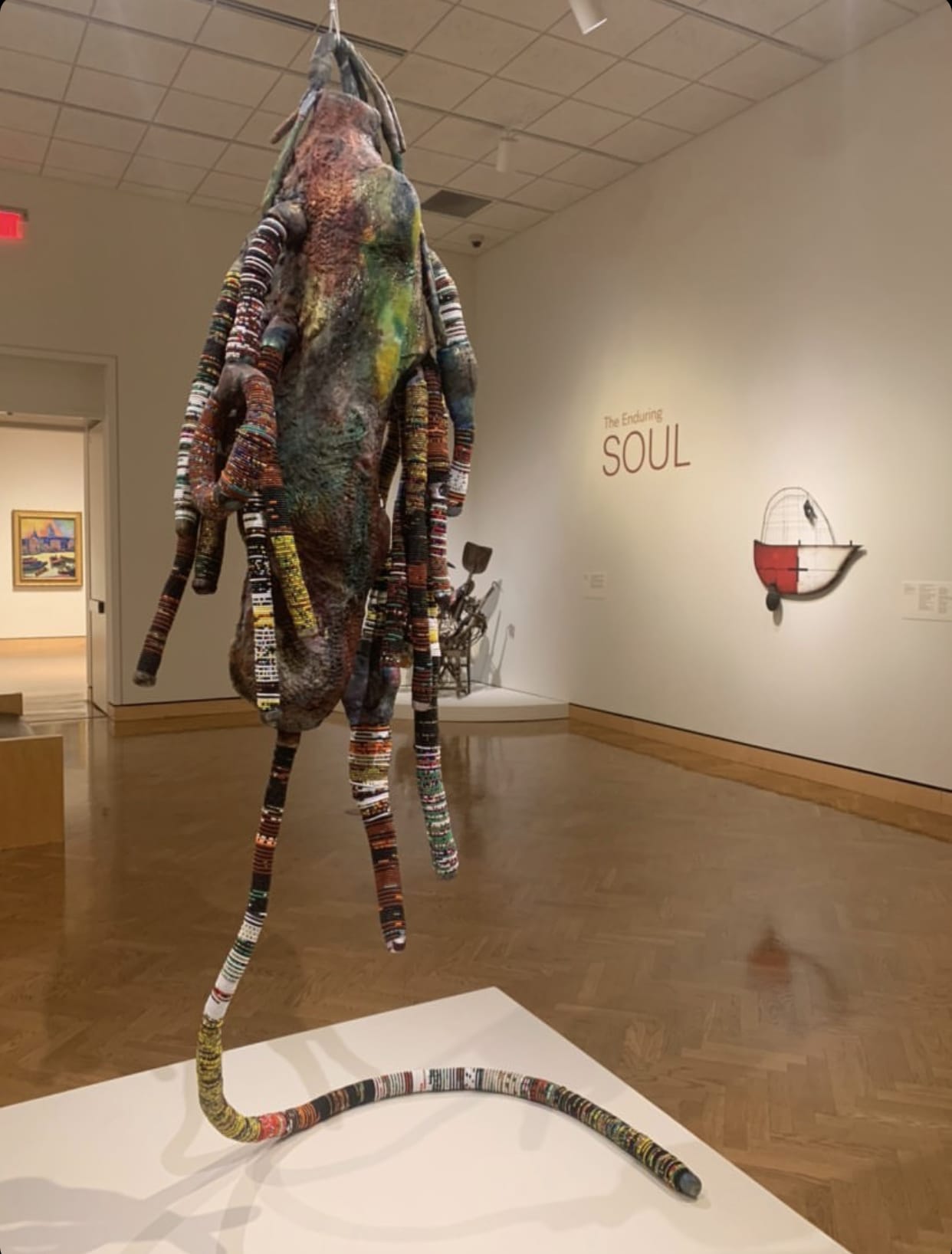

The ideas behind my process are ones that often transcend their own materiality in ways that are linked to spiritual and ancestral dimensions. I use materials like fiber, textile and beads and transform them into artistic expressions beyond the Western canon. Each bead, each strand, each form wrapped and bound pulls from traditional African healing and spiritual practices. Similar to an nkisi (a Kongo spirit charm), my work is akin to power objects created from repetitive, conjuring actions, and a series of rituals that pull together various energies and forces. In essence, it is a repository of personal and collective histories.

What are the themes and reflections from which your works arise? And how do you proceed to give shape to the idea?

Naturally, the themes and reflections in my work arise from memory, dreams, research, history, imagination and the phenomenological experience of being in a black body both personal and shared. After years of active addiction and a self-destructive lifestyle, I began searching for healing, transformation and a sense of purpose by connecting to my roots-an emotional experience that enabled me to link up with something familiar yet very ancient. I found many points of connection in African spiritual traditions. The first time I had set up my Egun altar (which is an altar for the living dead, the ancestors) various forms of unexplainable phenomena began to occur, ideas, images and sensations in my body at points identified as chakras-my third eye, my crown, and my sacral chakra in particular. After midnight, I would sometimes hear knocks on my door and no one was there when I opened it. After taking a spiritual bath, I could feel the sensation of someone sitting on my bed and touching my feet to let me know that I am loved and safe-a very warm and healing sensation. I began to have visions of my work or the knowing feeling of things that would later materialize and apparitions. At times, an uncanny ability to predict certain outcomes like the time I was given instructions in advance which actually saved me from having a car accident. I have always had very magical, multi-colored dreams with messages containing spirits, words or phrases and insights-the dreams contain colors like my sculptures. I move through the world with a strong sense of intuition, an inner knowing-the sense that I am being guided when I have the courage to trust and to listen.

All of these experiences inform my practice from a place that goes beyond the rational or intellectual faculties of the mind. When I had embarked onto these paths of initiation, into Lucumi or Palo Mayombe, I realized that all my life these African retentions had been there all along, hidden in view, because our colonized perspective often inhibits our ability to see all these connections clearly. I had been surrounded by these practices through my grandmother who was a spiritualist. She had an entire apartment dedicated to personal altars associated with African deities throughout her home. I realized that my mother’s love of music, theater, opera, her sense of design, color and style allowed me to imagine that I could create my own aesthetic. My father’s love of history, revolutionaries like Che Guevara, various books and the way he communicated through diagrams, also greatly influenced who I would become as an artist. When I had encountered ideographic writing systems in the Mayombe ceremonies it all felt sort of like home to me.

My ideas come to me from everywhere both inside and outside of myself, and most importantly from the work itself. I reference books, art and nature. When I take about long walks, especially in nature I gather ideas from the root-systems of trees and plants. I’m thinking about content symbolically, archetypally, and in terms of constructing cosmology and a sense of currency that I use to create my world. The materials have a history and are associated with layers of metaphor. The beads and the materials are the building blocks for creating my sculptures. The ongoing image I have about my ideas materializing has to do with imagining the parts of my sculptures as a nucleus. I create several nucleus-like structures which expand like a spiral. and I think of each nucleus as part of a constellation of ideas or as part of my singular vocabulary. I use a visual vocabulary informed by ideographic writing systems to construct complete thoughts accompanied by complex sensations like sentences or paragraphs.

What are the materials and techniques you prefer to use for your works? Is there even a symbolic or conceptual reason in their choice?

The structure and materiality of the sculptures manifest my own personal cosmology, grammar and visual lexicon. My primary materials are fabric and glass seed beads but I also use various other materials to varying degrees depending on the piece that I am working on. The other materials that I use in my beaded sculptures include: monofilament, string, dolls, mannequins, coffee grinds, gel medium, plant-bundles, coins, and acrylic paint. The materials I use operate on three levels: structural, aesthetic, and metaphoric.

In 2010 I started using fabric in a curtain-like assemblage sculpture titled Beings Born From Word And Stitch. The sculpture took over a period of nine months. The nine months symbolize the period of a mother’s pregnancy around which time Maia, my own daughter, was born. I was also giving birth to the new direction that my work was to take. In this piece I used fabric in a polychromatic palette used in the egungun masquerade of the Yoruba in Nigeria. The polychromatic palette is in part inspired by Yoruba color theory where colors are connected to various gods and reflect the temperaments of the gods. Colors are also references to Osain-a deity that owns the forest- and his medicine is found in the forest in the form of leaves of different colors.

In this piece there is also a connection between the curtain-like structure of the sculpture and the veil seen in an Egungun masquerade headdress. Egungun plays on the words for “bones” and “concealed powers”. I envisioned the tubular structures to be the bones of the work, an embodiment of shapes and forces concealed by the beadwork and informed by Kongo-derived ideographic writing systems. The veil in the headdress mirrors the curtain-like structure of my piece and is a metaphor for the threshold between the world of the ancestors and the world of the living. I felt it was important to spend significant time describing this particular work, because although it looks distinct from my other work with beads, I believe it is the mother sculpture that gave birth to the ongoing series Paraphernalia Of The Urban Shaman M:5. This is a moment in the trajectory of my practice where I am beginning to think of art objects in a tactile, magical, three-dimensional, and ritualizing manner. This new perspective allows me to experience and see the artist as a bridge between the material and immaterial worlds. In thinking of myself as a channel, a conduit, a ritualist, a conjurer and a type of “urban shaman” it situates my practice between the physical and spiritual world, at once sacred and yet secular.

This was also a breakthrough piece for me because it involved letting go of painting as the dominant or exclusive mode of creating. I began to reinvent myself and my language when I let go of thinking of myself as exclusively a painter- a thing that I associated with the canon and symbols of colonization. It was the beginning of using other kinds of materials that are outside of the Western concept of fine art. I started using materials that are often considered craft or “low art” and transforming them into a complex and innovative visual language. Working with rituals and materials used in conjuration like fabric, beads, coffee, achiote, rum, eggshell powder and coins was a transformative and healing process for me. I was able to connect to the metaphors and histories embedded in them. I began to see these as instruments of transformation, a kind of paraphernalia which led to me titling the series The Paraphernalia Of The Urban Shaman: M5.

My visual language corresponds to the idea of how in African practices the visual, the aural and the tactile are connected. Visual patterns, rhythms, sense of touch and other multi-sensory experiences are connected. My work reflects a tendency to pull from multiple African spiritual practices. As an “Urban Shaman” I imagine the rituals and systems of creating a new world with its own language informed by both ancient and contemporary cultures. There are times that I ritualize my process in ways that are both personal and simultaneously echo traditional ancestral modalities. At times the ritual looks like reciting affirmations while spraying my sculptures with white rum as an offering to ancestors who inspire and guide the process. The plant-bundles I have used along with coins and written prayers are another way that ritual enters the work. The aim of the whole process of making a sculptural object is to transmute, alchemize and manifest the cosmic energy-signatures that I am locating within myself as a multidimensional being. I imagine that through the concretization of the sculptures I am also transmitting the energy-signatures of our time, the ancestors and the world at large.

Recently the Claire Oliver Gallery proposed your personal “Across Seven Ruins and Redemptions_Somo Kamarioka”. What are these works about?

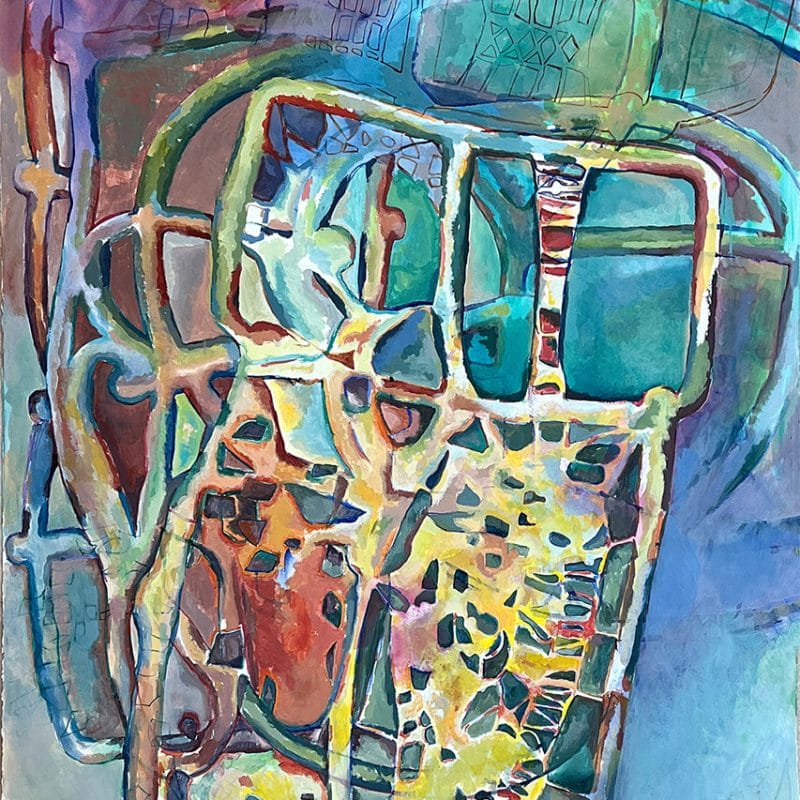

This body of work, Across Seven Ruins and Redemptions_Somo Kamarioka, comes out of a year of incredible transmutations in my life, of separations, of my initiation into an African diasporic religion known as Regla de Ocha and my relocation to St. Croix in the U.S. Virgin Islands. I am surrounded by the aftermath of slavery and colonialism and a people living in various stages of ruin and redemption. This series continues the mythology and origin story of a character I have created called the Urban Shaman. This character responds to the ongoing transformation of my own life from a boy growing up in some of the roughest neighborhoods in NY and the self-destructive behaviors and trauma that resulted. The Urban Shaman represents an archetype that negotiates the shadows of these ruins and reflects a personal and collective struggle to find redemption. Each bead, each strand, each form wrapped and bound pulls from traditional African healing and spiritual practices. Similar to an nkisi, my work is akin to power objects created from repetitive, conjuring actions, and a series of rituals that pull together various energies and forces. It is a repository of personal and collective histories. The paintings are a type of mirror as they are created from tracing parts of the sculptures. This reflects both the Kongo-derived traditions of connecting to a twin-self in the spiritual world and creating an ideographic writing system. The paintings evoke aqueous vessels inspired by the captive Africans and the voyage across Atlantic during the Transatlantic Slave Trade. As an alias to the Urban Shaman, Somo Kamarioka is a creolized mixture of Spanish and Kikongo that loosely translates to “we are chameleons”. On a material level it references the metamorphosis of the beads, string and fabric. On a spiritual and intellectual level it reflects the adaptive survival strategies and chameleon transformations that occur- both personally and collectively,-as we navigate various systems of oppression. In spite of the trauma and the violence, Across Seven Ruins and Redemptions_Somo Kamarioka materializes a journey of hope, healing and self-determination.

Is there a work that most of all has deeply involved you emotionally, intellectually and spiritually?

Overall, the ongoing series titled, Paraphernalia Of The Urban Shaman M:5, has compelled me to invest and immerse myself deeply. Within this series, one among many powerful pieces comes to mind: “That Which Weaves All Of Time Together”. When I was making this sculpture, I kept thinking about death, renewal and regeneration especially in the context of divinatory tools such as tarot cards which I use as points of reflection. I was undergoing tremendous personal transitions that were like deaths, separations that were a kind of undoing, and I was also putting myself and my life back together. The undoing was also mirrored in society and this current moment in the world during the pandemic and the civil and racial unrest of 2020 with George Floyd and Breonna Taylor. In a way, what’s going on in this present moment is not so unique as you can see the parallels between the past, present and future.

As I was thinking about death and regeneration and transformation and undoing, I was also thinking about something my spiritual godfather told me once, that love is the most powerful force in the universe. It got me thinking about love, not just in the romantic sense, but that all of creation, the magnificence of the world, is created through the vibration of love. It’s something that is cosmic, it evokes the original force of creation. In that way, it can also be seen as a muse. I was tapping into this energy throughout the making of this work, a muse that was an actual person in my life and also the actual ancestral and spiritual forces that walk with me.

Life balances itself out. While certain things in my life were going through a dissolution, new connections and new ways of communicating and new ways of expressing the self were also occurring.

The act of making, the ritual, my conjuring gestures, the stringing of beads was weaving my life together, it was transforming it, it was healing it. History is commonly viewed as the gathering of events which occur across a linear line, but history is also a repetition of eternal themes, like love, death and the afterlife, and those are the things that weave time together.

What are you working on right now? What are your plans for the future?

I plan to continue to develop the language and the ideas in my ongoing series Paraphernalia Of The Urban Shaman M:5. I see the work growing stronger, expanding and evolving. I envision myself creating projects in other modalities: paintings, videos, photographs and audio projects I call Soundsculptures. I see these other modes of expression as extensions of my vocabulary, aesthetic that reflect the alternate narratives of my overall vision. I am in the midst of conceiving ideas for a museum solo exhibition that centers my sculpture in conversation with works created in various other disciplines. I’m currently conceptualizing and materializing a new cycles of sculptures and works on paper-drawings I call “paper-cut-forms” like my GAR (Galveston Artist Residency) series called Afrosupernatural: Entities And Archetypes. Also, in progress, is a large totemic sculpture titled The Voyage Across Seven Chambers: Poesy To All The Goddesses And God Of The Sea. While reflecting on the various tones of blue beads and fabric contrasted with white, I began to recall my Ita, (4 hour divination session I received during my initiation). During this session, I was told that I am a child of both waters, meaning a child of the orisha (Yoruba diety) that owns the ocean, Yemaya, and the orisha that owns the rivers, Oshun. In short, this is a piece about the interrelationship of various systems of belief, cosmology, eco-systems, and the neuropassageways of the brain as a metaphor for the relationship between the larger universe (macro) and the universe of the world in one’s mind (micro)-the link between the inner and outer world, the relationship between spirit and matter and various cosmic dualities.