TANJA BOUKAL

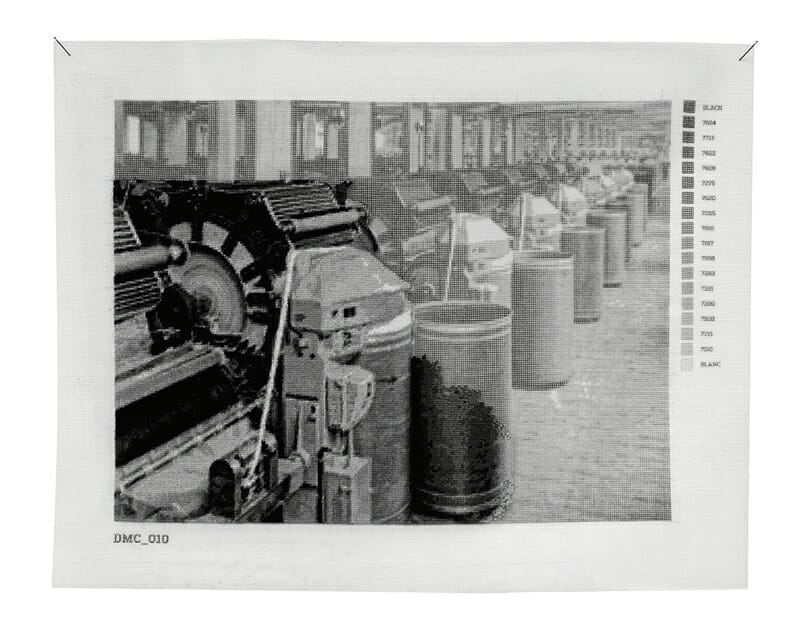

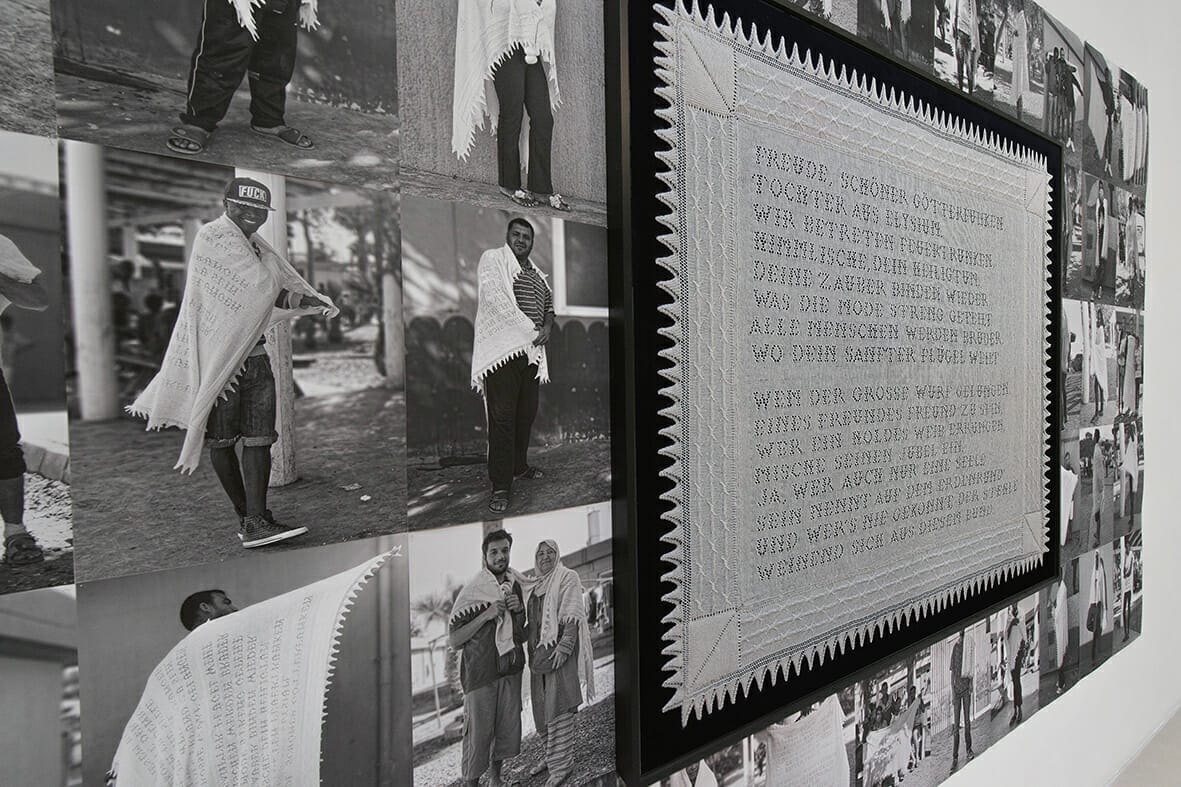

*Foto in evidenza:Unfinished 2012–2013 75 pieces, 21 x 30 cm each Embroidery on Canvas https://www.boukal.at/en/gallery-e.html/unfinished/

Tanja Boukal was born in Vienna in 1976, where she trained at the HBLA Herbststraße and graduated in Scenography and Decoration at the Wiener Kunstschule.

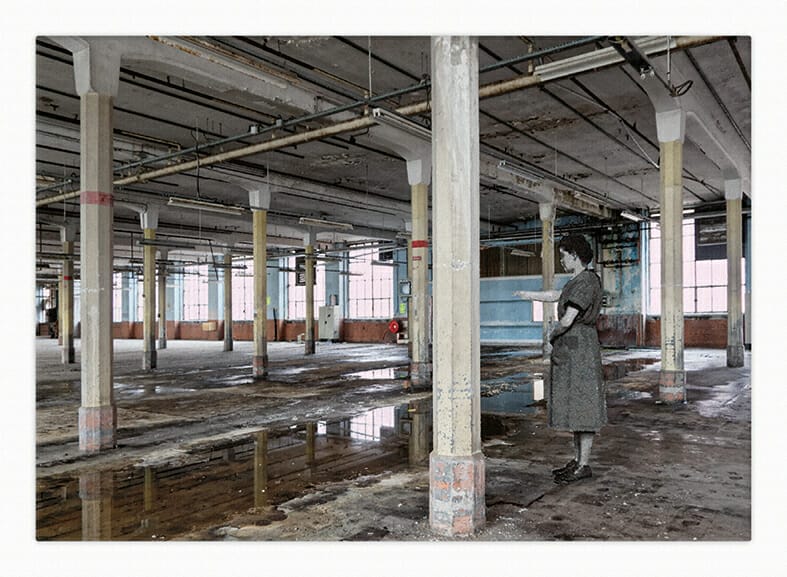

Human beings and their interaction with the environment and society are the core themes of her artistic research. Particularly, how they react to their life situations and changes interests her to the point of making them the subject of observation and, almost, of ‘study’. She’s fascinated by the different solutions and strategies we put in place – more or less consciously – to achieve our goals in the pursuit of happiness. From the fundamental principle of human dignity, Boukal explores the elements that transform ordinary people into the extraordinary, bringing them, through her work, to the centre of the scene, retrieved from the marginality that subtracts them from our attention. Not the individual as such, but rather his peculiarity that becomes representative – a kind of archetype – of a multitude of people who face, overcome and defeat similar hardships in their path.

In her work, she employs traditional craft techniques that have been the art form of generations of ordinary men and women, expressing their creativity and joie de vivre. These means have enabled them to leave a memory and testimony of themselves and the artist to establish an almost personal contact of continuity.

An artist with an international exhibition biography, Tanja Boukal, has recently exhibited at the Haus der Kunst in Brno in the Czech Republic, the Ruth Funk Center for Textile Arts in the USA, the Kunstverein Augsburg in Germany and the AB Gallery in Lucerne, Switzerland. Her work was included in the group exhibition ‘The Very Fiber…Not Necessarily Domestic Goddesses’ at Bernice Steinbaum Gallery in Miami in 2022. She has exhibitions and participations in the public realm, museum and institutional spaces, as well as private galleries in Europe (Austria, Italy, Germany, Switzerland, France, Denmark, Greece, Finland, Luxembourg, Bosnia and Herzegovina, United Kingdom, Russia, Spain) Turkey and the United States.

We took advantage of her upcoming participation in an Italian project to interview her and learn more about her journey. And here is what she told us.

What is the cornerstone of your artistic research?

Usually, I start by doing research because I have a topic that has caught my attention. First comes a question and then research, and when I feel that I can no longer prepare the ground by reading I start looking for people to contact. I also do scouting trips. Sometimes, when the legal situation is tricky, I try to get a lawyer to advise me and, of course, all this is part of my preparation. In a way, these are the only safety nets that I’m able to put in place. I do historical research, I find out about the place I’m going to, its organization, the strategic districts, I also look for contacts on the ground. Often my first point of contact is a friend of a friend of a friend as it is important to have someone I can go to, just in case things go wrong.

In your artistic practice you use ancient, slow, patient techniques such as embroidery or crochet, albeit revisited in a contemporary way. What does this choice mean for you?

Textiles as a medium evoke emotions that strike much more immediately than other art forms. Almost everyone has a relationship with them. Be it that someone got a sweater knitted or a relative made cross-stitch blankets, most people understand needlework as something from their environment. To emotionally separate from the content of a photo or a painting is much easier, we can define it as “high art”, as something that has nothing to do with our lives. And then there is the haptic factor, many of my works can be physically touched. My work “Rampard” consists of 4.5 m high terry cloth panels that depict a European border fence. They are soft, fluffy and brutal in their depiction. People often stand in my exhibitions and touch them. The moment they grab them, they also grab the meaning.

Many of your works focus on women and their lives. How much are these instances part of you?

Well, I am a woman. And like all women who work with textiles, I am confronted with having to defend my choice in the field of contemporary art as an equal medium. There is a reciprocal relationship between women and craft, particularly the contradictory nature of women’s experiences: how it has shaped female subjugation throughout history as it was redefined from a highly respected male profession to a female pastime, while at the same time it was, and still is, an immensely pleasurable source of creativity and connection between women. Quite often it is precisely these experiences that I use to find points of contact and establish connections that then help me accomplish my projects.

Your work turns the spotlight on small anonymous stories that are common to many people and to many lives, giving voice and shape to everyday heroism by transforming personal experience into universal. How are your works born? What are the areas of interest of your research? How do ideas take shape?

Often it starts with information I come across in the news, which is rarely processed and presented in detail. I start asking myself questions. Then I start looking for answers to these questions. These answers are often found abroad. It is very important for me to travel and to see things.

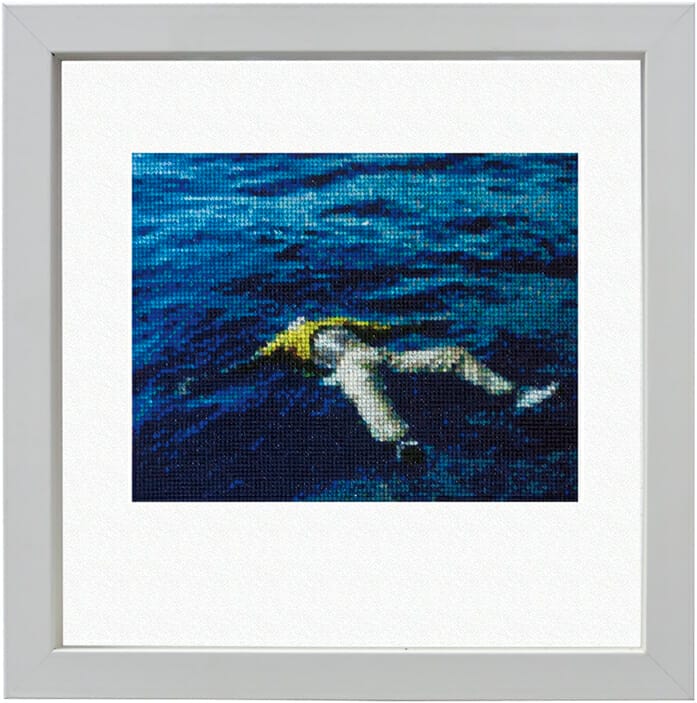

For instance, for my “Aegean project” I went to Turkey in 2016 because nobody could tell me what was really going on there, how the refugees organized their escape. These are things that nobody talked about then—nor does today. We all know that there are boats. We see all these people arriving. We even know where they come from. I was interested to know what happened in between these known facts. First-hand understanding of all the circumstances is key to my work. It is important that the answers I get are a reflection of events and of the opinions of those who speak to me. I have to go there, ask people, and see the situation with my own eyes.

As I travel alone, I communicate with a lot of people. So I hear a lot of stories and these stories are quite often the base of my work.

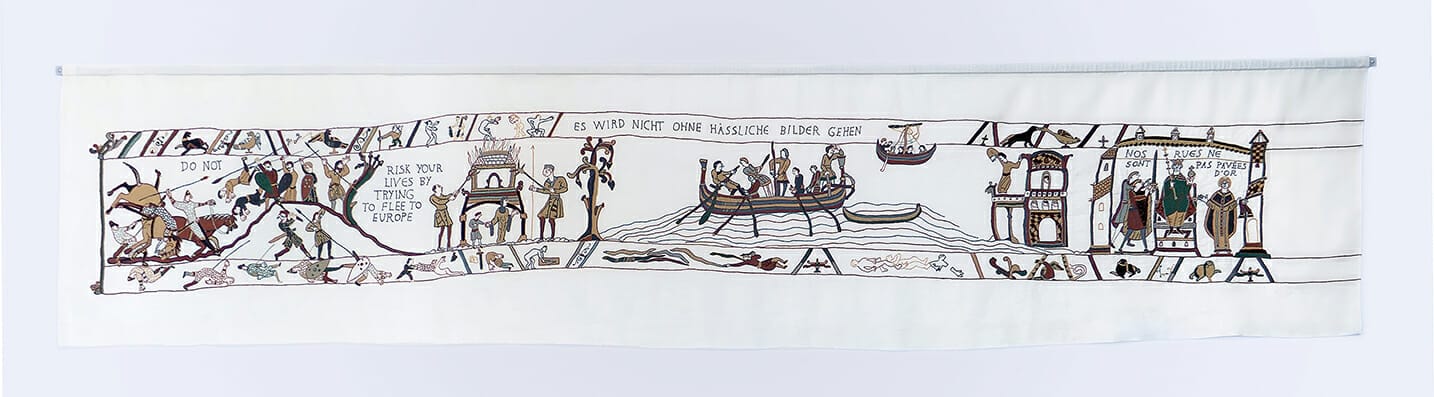

Some of your projects develop through investigative and documentary work that resembles that of a journalist – I am thinking, for example, to The Melilla Project or the re-edition of the Bayeux Tapestry 2.0 which reveals the words of the propaganda published on institutional sites. What does it mean to you to make art? What do you think is the role of the artist today?

Artists will not save the world, but they can put a finger on a wound. Especially in a museum context, visitors rarely expect to be confronted with current political problems. I try to take a very personalized look at big problems, to show that there are individual fates behind huge buzzwords.

Actually, I wanted to become a journalist, but I found a better way for me to tell stories.

I can take as much time as I need to explore places and events without having a deadline. Being an artist gives me a jester’s cap. I can hear a lot of things that no one would tell me if I were a journalist. And I transport my personal point of view. I am not objective. I tell my own truth. I show how I see things, from my perspective of a white, European woman.

Very often, when I’m asked to take part in a conference, to speak at a congress on human rights, to give a talk at a museum, I can sense the disappointment in the room when I announce that I’m only going to speak about what I have seen, and I have to immediately remind people that they must be aware that this is my perception of things and that I can in no way speak on behalf of others. I am only trying to understand what others think.

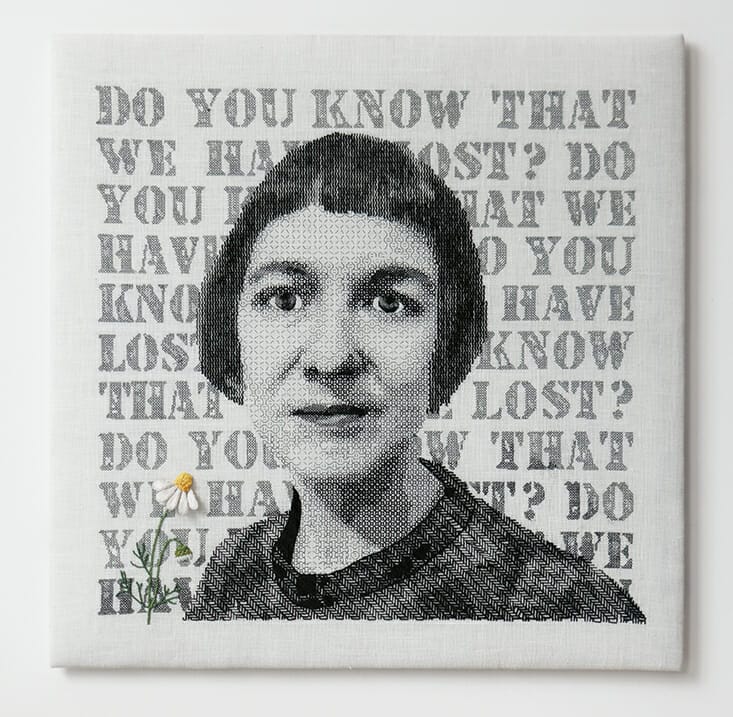

Your recent exhibition is “Do you know that we have lost?”. What and why did we lose?

Choose something where you feel you lost. Be it the supposed freedom of choice, the standard of living, solidarity, the climate change, wars, refugees or something else. Tactics of the last years to make the world a better place whether legal, political, activist or artistic have resulted in little progress. For me there’s no use banging my head against the wall anymore. Either your head will explode or they will simply open the door and let you in. Either way, no house will come crumbling down.

I was discussing this generally depressive mood and feeling powerless with a friend and what to do about it. “What if we lost?”, he said very frustrated and it sounded so depressing to me. I wanted to disagree immediately, of course, because having lost was an admission of failure for me. But then I thought about different grief management strategies. Couldn’t admitting failure also open up new opportunities? Realizing that we lost can be a powerful thing both depressing and liberating. When we admit that we have lost a battle, we may be able to break new ground and win the war. And I believe that we desperately need this. New ways to live our lives and to improve the general state of the world.

Following that thoughts I made a self portrait called “Do You know that we have lost?” in blackwork embroidery combined with a chamomile done in stumpwork technique against the background of the work’s title. In the Victorian language of flowers, the plant signifies “energy in need,” an enterprising spirit and healing. And so the seemingly melancholic work transforms into a challenge and encouragement.

Who are the artists who have inspired or influenced you the most?

Very different artists inspire me. Nan Goldin’s deeply personal narratives, which grew out of the artist’s own experiences, made me realize that I have to live through things to grasp them. Francisco de Goya’s “The Disasters of War” opened my eyes to the power of journalistic aspect in artworks. Louise Bourgeois and her exploration of grief and guilt caused me to reflect on my own remorse, memories, and positions.

But there are many other lesser known artists whose work has touched me deeply. Be they visual artists, photographers, writers, singers or artisans. No matter how recognized an artist is, what ultimately matters to me is whether a work evokes emotions in me, be they positive or negative.

Alongside the artistic path you also have the didactic, laboratory and editorial professions. How important is the relationship with other people, communicating and transmitting ideas, reflections, skills, etc.?

Communication is everything in my work. Without it, I could not accomplish any of my projects. To establish good communication, I need to build a relationship with people.

Do ut des (Latin for “I give so that you may give”) is key.

I share my experiences, fears, doubts and questions, and in the exchange I gain insight into the experiences, fears, doubts and questions of my counterpart. I learn a lot in these encounters, and I like to share my experiences. Be it in writing a blog during my projects or in the form of lectures.

When our traditions, our knowledge and our skills have disappeared, we become a culture without a past.

That is why it is also important for me to teach handicraft techniques. The ability to practice them became a commodity reserved for a dwindling population of craftsmen and artists. It was considered a necessary but now pushed aside and relegated to the status of a hobby or a luxurious pastime. If we don’t spread the knowledge, it will be lost.

Which of your works or projects has most and profoundly marked or involved you?

I can’t name a single project. I have learned an incredible amount through each one. Perhaps my greatest realization is that I am incredibly fortunate to live in a safe country and have a passport that allows me to do so. But I also learned how fragile it all is and how quickly life circumstances can change. I take nothing as granted and remain vigilant, trying to treat people as I would like to be treated and trying not to fall into despair and cynicism. This is exactly what working with textiles helps me to. Sitting down and putting one stitch after another, focused and concentrated on nothing but the next movement helps me again and again to create the strength to develop the next project.