The century of “variety”: the history of fabric from 1700 to 1750

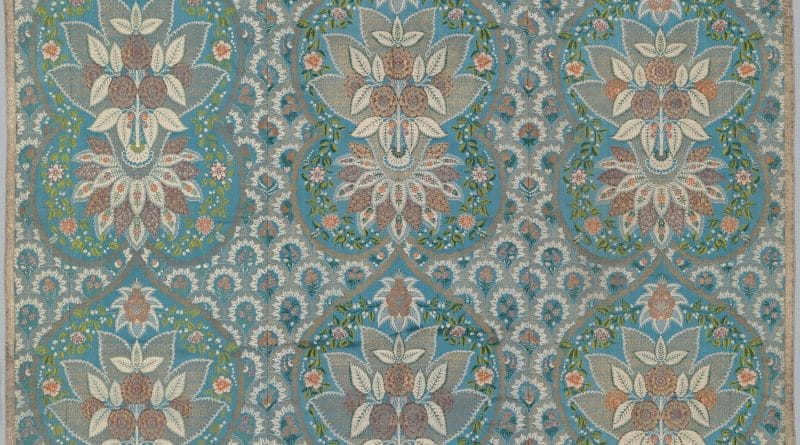

*Featured photo: Lace pattern silk fabric, France, 1720. © 2000–2022 The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Public domain

The eighteenth century is a century characterized by an extraordinary variety of decorative textile typologies obtained with very elaborate techniques. The diversification between fabrics for clothing and furnishings, which took over in the second half of the 16th century due to the emergence of a different concept of living, greatly influenced the style and technique of the textiles. In fact, between 1600 and 1700 various types of fabrics developed, including fabrics with “lace”, “bizarre” and “meandering” designs or even those in the “Revel” style, just to name a few. Specifically, the new taste in interior decoration – which established itself in Versailles under the reign of Louis XIV, thanks also to the growing development of French manufacturing industries – will lead to the codification of solutions that will be repeated again throughout the following century and beyond. In this general context, some professional figures, such as designers of patterns for fabrics, acquired an unprecedented importance on an artistic and social level.

Suffice it to say that the success of some categories of fabrics was due precisely to their creative ability!

The progressive expansion of the markets, the increase in social groups interested in the “fashion” phenomenon and the rapid changes in taste required an ever faster replacement of motifs, so much so that real textile design academies were founded in various European centers as a Lyon, Florence, Vienna, Venice and Genoa.

Below we present some of the decorative motifs coined in the period under analysis:

The creation, between 1685 and 1730, of a type of fabric called “lace”, perhaps conceived as an alternative to the very expensive Venetian needle laces that at the time covered women’s and men’s garments, is certainly attributable to the Lyonnais manufactures. These are large, modular motifs that reproduce the candid lace design. Initially simple then double-pointed, starting from the second decade of the 1700s the design solutions will tend to increase the spacing between the parts, to the point of giving way to naturalism.

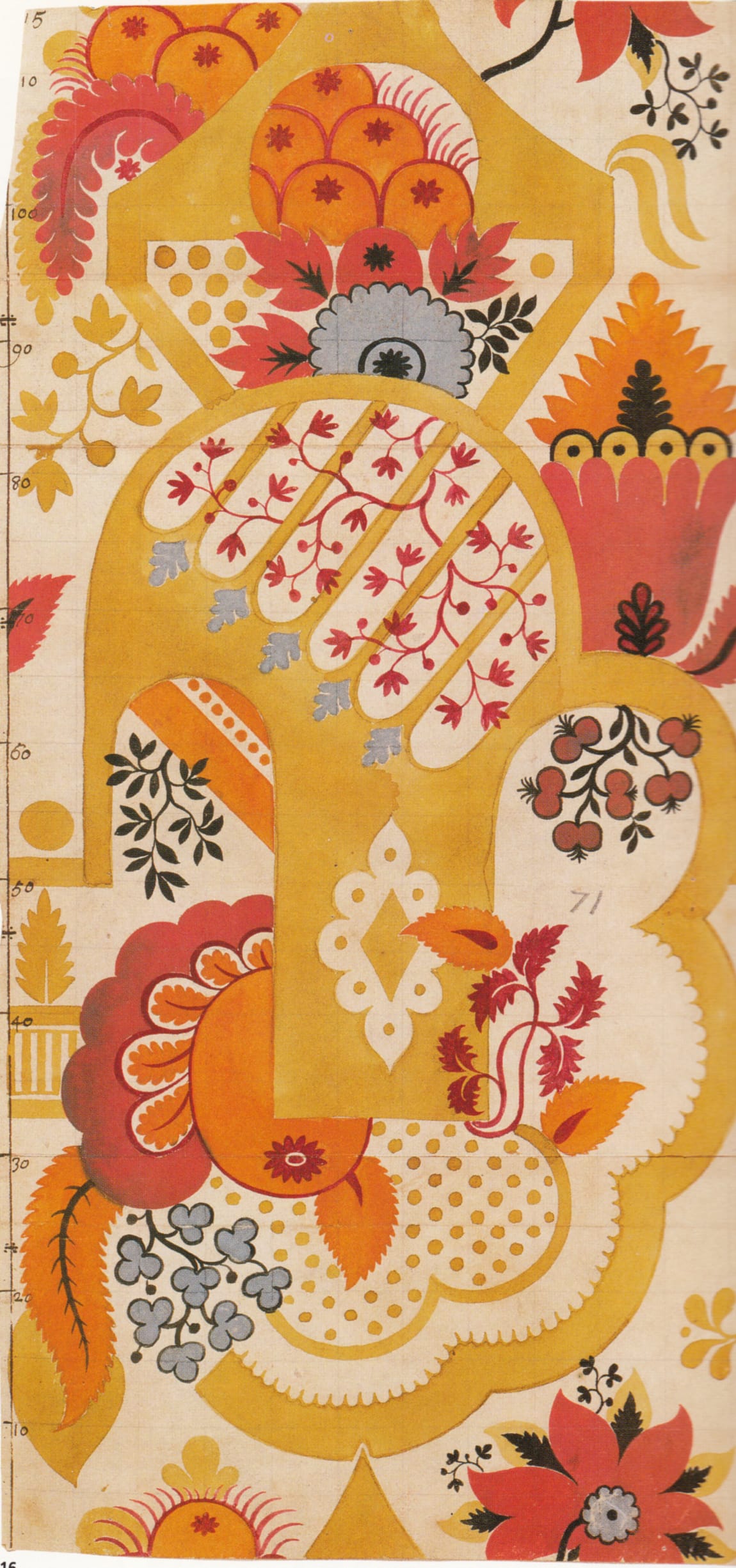

Another particular model of fabric that characterized the early 18th century were the “Bizarre” design fabrics (a term coined in 1953) which, although completely breaking with the previous tradition, were produced for a short period of time (1690-1720). Nonetheless, many have survived thanks to the sudden thematic change and the pressing manufacturing production.

The decorative motif of bizarre fabrics is conceived as a moving surface where the undulating and / or spiraling pattern prevails. The traditional elements, if present, are always reinterpreted, differently associated and transformed.

Arguably, these lush and extravagant fabrics were by no means “bizarre” for contemporaries as they fit perfectly into the cultural and artistic context of Europe between the 17th and 18th centuries on a stylistic level. Just think of the spread of the collections of artificialia and naturalia, the surreal gardens of Bomarzo up to the paintings of Arcimboldo: collecting meant collecting unique, surprising objects from recently discovered lands including Japan.

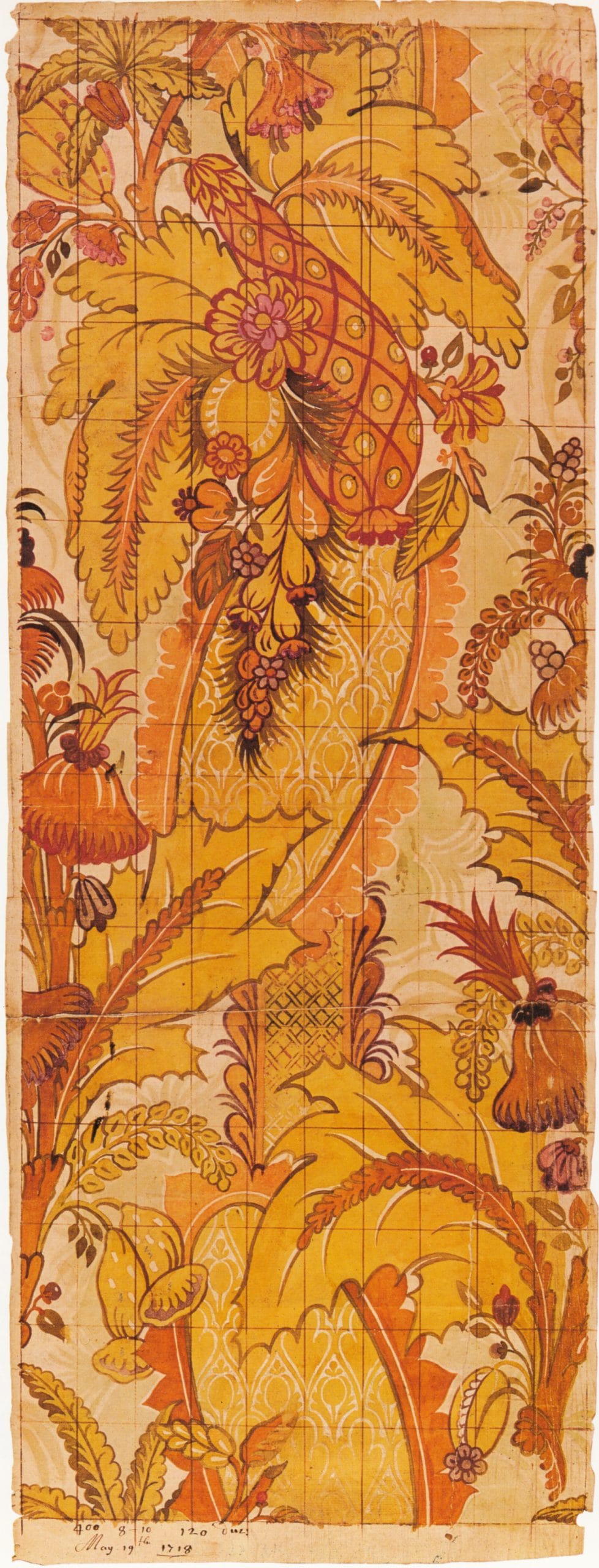

The constant search for novelty resulted in the tendency towards naturalism around 1730. The setting of the design consists of bunches or slices of flowers, fruit and leaves, which rest on shells, baskets or pedestals, arranged with extreme freedom and a three-dimensional relief effect from the bottom.This production, considered one of the most luxurious for its variety of themes, technical complexity and chromatic assortment, is mainly linked to the Lyonese draftsman and painter Jean Revel (1684-1751), son of a painter from the circle of Charles Le Brun.

He introduced a technical device called “point-rentré”, that is a drawing effect obtained by alternating the untying of two wefts of different colors or two tones of the same color, which allowed to introduce a three-dimensional pictorial approach to textile manufacturing. He replaced the combination of flat colored backgrounds, making extensive use of black and white to blend the subjects in order to accentuate lights and shadows.

Paradoxically, the naturalism of the nuance was used to create motifs that did not respect the real proportions, in which fruits larger than architecture appear together! In this the link with bizarre fabrics remains evident and so is the influence of Indian models spread in Europe by the printed cottons.

This technique was combined above all with the so-called “island” or “clod” decorative motif consisting of a rigid horizontal layout, where, for example, architectural elements hover without support and small shelves hold huge vases full of flowers in a total absence of logic.

Bibliography:

Devoti D., L’arte del tessuto in Europa, Bramante Editrice, Milano, 1974.

Sitography:

http://mda-arte.blogspot.com/2012/07/la-moda-femminile-del-settecento-tra.html

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=14780879

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=14784323

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=14784353

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bizarre_silk

https://www.metmuseum.org/

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=27299224