Interview with artist Ruth Miller: my Medium is Embroidery

Ruth, where did you learn the art of embroidery?

Ruth, where did you learn the art of embroidery?

I learned to embroider at home when I was a young girl of approximately 8 to 10 years old. At this time, needlework was still a somewhat typical womanly skill. Along with sewing, crocheting and knitting, It was a way to pass the time before we had a television and also was a skill I could use to provide products for myself. I forgot the knitting right away but continued to make my own clothes and later to crochet small accessories to earn extra money. Embroidery was at first a source of entertainment for me. It added flair to my garments but the time spent on it was also a way of playing with color and geometric patterns.

Why the choice to use thread instead of paint, which is faster?

In childhood, whenever I attended a structured art class, we were handed paint to work with. Then, at Cooper Union the quality improved but still its slippery, greasy texture remained and was combined with the use of noxious chemicals to thin and clean it up. But paint of various types was presented as the only professional medium for 2-dimensional work.

Then one day, I saw a woven abstract figurative tapestry by Senegalese artist Papa Ibra Tall. I immediately recognized that with embroidery I could make painterly effects with threads that are clean, soft and dry.

Although I didn’t think about it at the time, whenever I sit to embroider, I am connected in spirit with my aunt who lovingly stitched with me as well as all the numberless women of the past around the world. It’s a strange but wonderful phenomenon.

Can you describe how you went from making embroidery to large tapestries?

Because I had been such a shy young person, my first inclination was to make small things that took up little space, that didn’t intrude, no matter the medium. Even my handwriting was small.

When I was at Cooper, bigger meant stronger in effect and, therefore, better. The same is usually true in today’s contemporary art circles. In order to feel accepted and to have my work valued, I started to work in a larger format. I also recognized that the change would be a way to offer a personal challenge to myself, a way to allow myself as well as my creations to take up space. I lived up to the challenge and came to enjoy it.

Now, there is the opposite situation. I’m having to figure out a way to work differently. As my work becomes more well-known, there is pressure to make more pieces at greater speed. In addition to the amount of time embroidery requires, there is the need to travel and publicize the work. And, since I know no one who can help me stitch, the only way to go seems to be toward smaller pieces. Some famous contemporary painters as well as artists in the past have delegated parts of their art – if not all – to be completed by teams of people. However, some of the ideas for artistic enhancement arise only in working moment to moment. Changes in design are one thing but there are also calls to make philosophical adjustments that my mind responds to when my hands are busy doing the work.

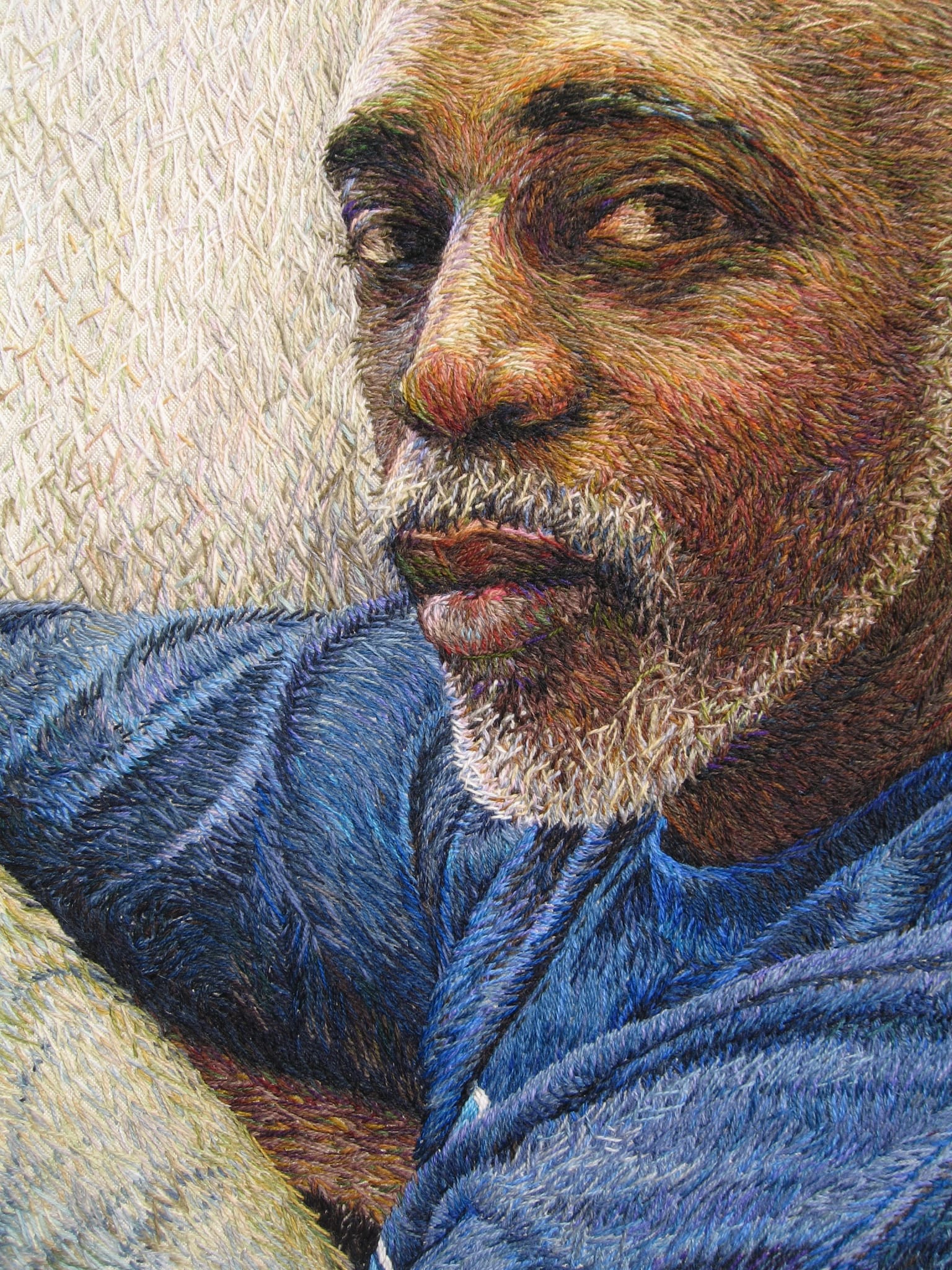

“THE IMPOSSIBLE DREAM IS THE GATEWAY TO SELF-LOVE”

35×25 inches

Hand-stitched embroidery, copyright by Ruth Miller.

“In this piece, I had fun using my knowledge of color theory to blend orange, lavender, lime green, blue, beige, pink, cream as well as the expected browns to depict the skin tones. This was also done for a very practical reason: I was running out of browns. They say, ” Necessity is the mother of invention.”

Can you talk about your creative process? Where do you get inspiration, how do you plan your work and what are the different moments of design? What are the steps that lead you to the finished work?

Most often my ideas come from internal struggles in my life. I’m very introspective and analytical. Also, I read a lot. Perhaps heartache, introspection and self-analysis combine with external ideas and by some magic, they coalesce or crystallize in my mind. I would love to make a funny piece but somehow pain seems more immediate than amusement. I have to get it out so I can rest.Generally, I begin with a few narrative ideas. I search for a model to embody them, then photograph the model. (I’m a pretty bad photographer but I work cheaply.) Sometimes an unexpected moment in the photoshoot will suggest an additional narrative. Next, I choose the most engaging pose and use pencil to make a simple line drawing with no shading. When finished, I photocopy that image several times to make shaded drawings and drawings using colored pencils for different color schemes. When I finish the most likely image, I return to the photocopied line drawing, make a grid over it, transfer the grid to stretched fabric and reproduce the line drawing on the fabric. From there, I begin embroidering. Throughout the whole period of stitching, the photograph, the line drawing, the shaded drawing and the color study will all be kept beside the piece for reference. I observe the progress of the piece from close up and at a distance. If the piece is very large, I cannot reach all the parts from one side so I must turn it and stitch from all sides.

It is ideal if the entire concept is complete on paper before I start. That way I won’t have to remove many stitches to make corrections. In reality, I am often impatient and start before the conception is solid. On occasion, I believe the idea is solid but get a better one once I get going.

I’m the kind of person who is most interested in conversations that involve an exchange of ideas, preferably ideas with a practical application. If I have no ideas, I should at least ask a question. So, at the base of my work is the idea of narration. In most instances, the narrative is explicit enough so that an observant person will catch at least some of it. On occasion, the narrative is private even if the work is shown publicly. Almost always, I hint at the meaning in the phrasing of the title.

This has been true since 2003, the first time I brought a tapestry to the attention of a wide circle of personal acquaintances. At that time, I felt that I had no stories of my own to tell. Yet, narrative was still essential. So I borrowed one that was similar to a proverb. As luck would have it, the preparatory work didn’t fit well with the proverb. It was a lot of work and I had no other theme prepared. But, as I worked on the drawing, another more personal narrative arose. That is the one that helped me realize I might have something to say.

“THE SISTERS”

16×20 inches

Hand-stitched embroidery, copyright by Ruth Miller.

“ The medium is sewing machine thread on fabric. The models are my daughters. In this piece I taught myself to reproduce both a reflection and a sense of transparency at the same time in the sunglasses. Your readers may also notice the use of colors (black, purple, brown, gray) instead of using all black in the dark areas”.

Do you use ancient techniques and materials?

Yes. The grid system of transferring drawings actually came from ancient Egyptian wall paintings. It was used to great effect during the European renaissance as well and was taught to me at Cooper Union.

Many old European tapestries and South American embroideries were made with wool and have lasted centuries. Consider the Bayeux Tapestry. I would love to make one like that with a long time-line. Other parts of Africa and Asia as well have long traditions of hand-stitched embroidery. In fact, the technique is so simple that it is probably found practiced world-wide. My one advantage is that wool now comes in so very many colors — over 400 are supplied by the company I buy from. Their tapestry wool is made with three plies. In order to achieve a smoother surface, I separate the plies and now primarily stitch with a single ply. This is possible only because of the wool’s quality. Each of the 3 plies is itself twisted. This type of construction gives it strength. If not for this, it would shred as I pulled it repeatedly through the fabric which is fairly coarse.

New embroiderers can find several antique decorative stitches from books to make their work more interesting. I like those but rarely use more than two or three types because they would take attention away from the narrative. Perhaps I will use more of them in the future.

“FLOWER TOO”

31×31 inches

Hand-stitched embroidery, copyright by Ruth Miller

“This is a detail that shows the stitching from a piece that was sold. It could be an illustration of the realistic nature of the work. Wool on fabric.”

What, in your opinion, are the artistic, esthetic and stylistic differences between small and larger textile works?

I think the main difference between small and large works is in visual impact. In considering only portraits made with yarn, I believe that more refinement of line is possible with larger works. Because of the thickness of the yarn, life-sized images are required in order to achieve the graceful curves of realistic renderings of flesh. The texture of the wool has an advantage over a completely smooth painted surface. Even a thin strand of tapestry wool casts a shadow that offers depth to our perception of a tapestry. This slight depth increases the subject’s presence in the room, especially since most of the portraits are life-sized. Unfortunately, this subtle presence is difficult to capture in a photograph. My tapestries must really be seen in person to be appreciated.

When an embroidery has lots of empty background space, I define it as a drawing. Drawings take much less time to make because of that emptiness. This is a nice change for me. I sometimes use wool but usually my drawings are made with sewing machine thread using hand-held needles. With sewing machine thread, it is also possible to create realistic work. It resembles pen and ink. And, although I can make them close to life-size, I crop the images smaller. This type of thread can be used successfully for very small works.

How long do you take on average to complete a tapestry?

About a year. That is how I estimate the stitching. I don’t count the time it takes to conceive an idea or create the reference materials because those things occur unpredictably. It takes two to three months, if the piece is small and well-planned. Maybe over a year and a half if it is very large. More if the planning is difficult.

In your opinion, what are the advantages and disadvantages of embroidery as an expressive medium?

During this period of contemporary art, embroidery is still somewhat unique and unexpected. This adds interest to whatever is created with it. Despite signs that say my work is embroidery, it looks like painting. Even people who work in art industries and know better than to touch the art will instinctively reach out to verify what their eyes are seeing. This interest is an advantage; the touching is a disadvantage since over the passage of time the oil from fingerprints could discolor the wool. For this reason, I try to exhibit my work where there are docents (people who both guard and explain the works on view) to restrain them.

Artistically, I see no disadvantage. You might think that not being able to blend colors as is done in wet media is a disadvantage. However, if the image is large enough, the different colored stitches can be arranged in such a way that the eye of the viewer will do the color-mixing for me. The long periods of time necessary to physically create a large tapestry are hard on the body but they also give me long periods of mental focus. Time allows me to see which parts of a piece don’t work. It also allows for development of layers of complexity in the narrative, sort of like what happens in life itself.

“CONGREGANTS”

20×36 inches

Hand-stitched embroidery, copyright by Ruth Miller

“Wool on fabric. It is the latest complete portrait. It is not yet on the site. In this piece I kept the realistic drawing style but used unrealistic coloring to highlight the various emotions the model is showing.”

You create mostly portraits of people with absolutely realistic features; why?

People are more interesting to me than any other subjects. In fact, looking at people we are engaged with many subjects at once. What is on their minds and in their behavior is interesting. Their physical makeup is interesting and there is a story to be seen in their features. I don’t mean in their expressions, although that is true too. I mean in the physical shapes of the noses the heads, the hair. I’m into old-fashioned things like phrenology. Is it 100% correct? No. Has prejudice and racism entered into it? Yes. But what what an interesting idea it is to read the body the way a palmist reads the hands. (Don’t laugh. I had a excellent palmistry teacher named Singh Modi and managed to learn it fairly well myself. I know whereof I speak.) Any competent doctor ought to be able to read every patient who walks through his door. I try to do so whenever I work on a new portrait. Suffice it to say, the differences in people reflect the lives that they have endured — again, not thinking of their facial expressions.

Speaking of excellent teachers, my drawing teacher at Cooper Union was Stefano Cusumano who showed me how to bring life to a simple line. Hannes Beckman taught a class called Psychology of Perception. In it, he transferred what he had learned about color theory from Josef Albers at the Bauhaus.

As an artist, there is a sense of accomplishment that comes from performing well. Realism provides a very clear way of judging observational skills and efforts in translating those observations into other media. I feel competent if I can quantify my technique in this way and each piece offers another opportunity for improvement.

With human subjects, almost every viewer has a reaction to them: good or bad. Realism speeds up this reaction. We have less work to do to figure out what is being presented to us. It’s like comparing the experience of seeing an object in the day with seeing it at night.

I mentioned earlier the presence in the room created by a good portrait. Before anyone else sees my subjects, as they unfold from my hand, I react to them. I see the models as individuals and with them is the narrative I’ve attached to the piece of art in which they now live. All this is in my head. And, with the passage of time, this hybrid person becomes a companion to me. It took quite a while to convince myself to let the earliest ones go. But, when they go to another place, they become companions to others. It is love of this process that keeps me stitching.