FIONA DAVIES

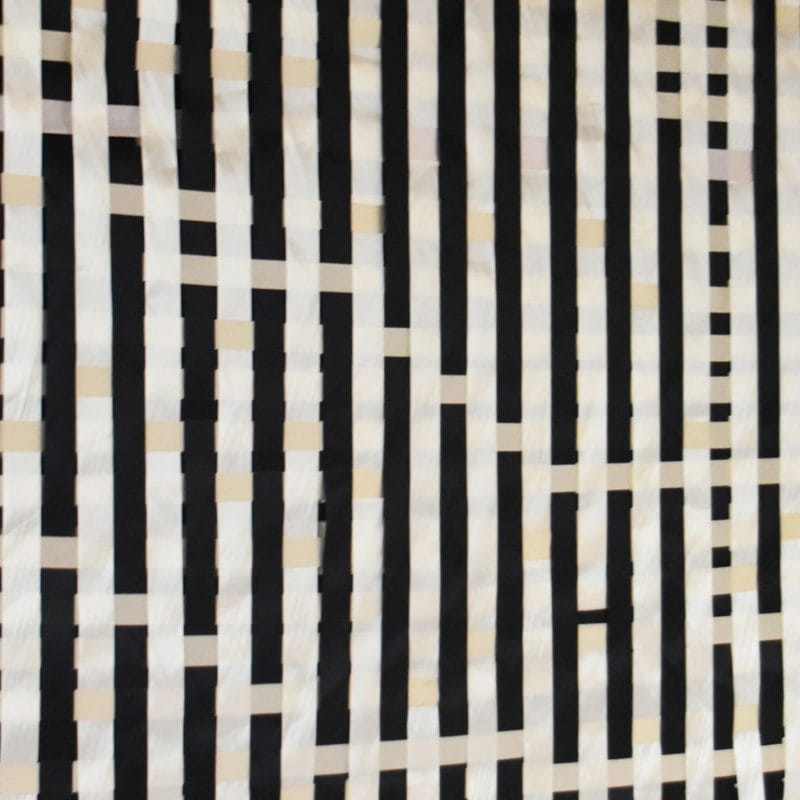

*Feathured photo: Blood on Silk: Surgery, 2013, ribbon, canvas, paint and wood, 525 x 360 x 20cm photo credit Alex Wisser

Fiona Davies is an Australian visual artist. Her interdisciplinary research investigates the processes, systems and dynamics associated with medicalised death in intensive care.

She has been awarded a practice-led PhD by the University of Sydney and holds a B.Sc, (UNSW), a Bachelor of Visual Art (UWS) and an MFA from Monash University.

Significant exhibitions and events from 2022 include curating and participating in Carnivale Catastrophe at Cementa22 and performing at the Lumiere Festival of the Moving Image at Mount Victoria.

Over the past two years, she has participated in numerous international online events, including Unfix Festival Glasgow UK, Athems Digital Arts Festival and the Limestone Coast International vVideo Arts Festival, BMCC and Unus Multorium at Plas Bodfa in Wales, UK. In 2019, she exhibited at the State Silk Museum in Tbilisi, Georgia.

She told us about her journey and the meaning of her work in this dense interview packed with content, emotions and reflections.

Ci ha raccontato il suo percorso e il senso del suo lavoro in questa intervista densa e fitta di contenuti, emozioni e riflessioni.

How did you come to art?

I don’t remember not being aware of and involved with art. I’ve always wanted to be making art. From a young age maybe six or seven, I discovered the pleasure in understanding and exploring materials. I became quite interested in mosaics and my mother used to bring me any odd highly coloured ceramic plates she could find at the Charity shop. I would break them up into small pieces that I could then construct back into a mosaic. One of the great pleasures of that time was just sorting the materials, putting them into glass jars, and playing with playing colour against colour, shape against shape. I think I only ever made about two or three mosaic works. But I certainly really delved into understanding the material of the broken ceramic-coloured glazed plates – how the colour was just on the surface, it didn’t go down the sides, unless you saw the edge of the plate. So, by I think by accident I spent a couple of years of my life just trying to understand a particular material by playing with it. And that has stood me in good stead over all the years of my practice.

I first found textiles as a way to make art when I was about nine when I was taught how to weave on an inkle loom by my great aunt Judith who later introduced me to a four-shaft table loom. After high school I studied Textile Technology at University in an Applied Science Degree and only moved to studying visual arts in my late twenties. The study of textiles at university focused on mass production, t, and uniformity of the final product. It led me to devalue the importance of the handmade. It wasn’t until several years after studying visual arts that I felt comfortable working again with fibres and textiles.

You are an interdisciplinary artist who uses different materials and techniques. When do you choose the textile medium for your works? What are the reasons behind this choice?

Often, I focus on an emotional landscape in my work and the role of the materials is to help carry the meaning of specific conditions and contexts. Textiles are so embedded in our lives they can be seen simultaneously through multiple lenses which include the precarity of labour particularly in clothing manufacturing industries, excessive use of resources in terms of fast fashion and ineffective recycling, enclothed cognition where specific uniforms such as the doctor’s coat or patient’s hospital gown impact on the response to that individual, and how a wide range of scientific textiles are able to adapt to specific user requirements.

To illustrate, earlier this year I made a work responding to the human/horse relationship during the massive 2019/2020 Australian bushfires. I wanted to find a material to make a series of horse costumes referencing the pale horse of death from the book of Revelations in the New Testament and the horse costume designed by Janine Jenet for Jean Cocteau’s 1960 film The Testament of Orpheus. I wanted a fabric that had first-hand experience of a climate catastrophe. Finally, I found a silk fabric which had been damaged during unusually high monsoon flooding in Kolkata. Like the fires this event could be attributed to the impact of climate change. The fabric was no longer considered highly desirable by the market but for this work the experience of being submerged in flood water and damaged added to the meaning carried by that material into the work.

Your research on the thin line between life and death in a context such as the hospital one is at the origin of a series of textile installations. How was this project born? How has it developed and evolved over time?

This project, Blood on Silk, was developed following the four and a half months my father was a patient in ICU (intensive care unit or critical care ward) prior to his death and the series of three installations I had made after his death.

In an ICU critically unwell patients are treated. They are those on the tipping point between life and death. I became really interested in the process of how you transition from life to death in a hospital setting, and particularly in and ICU. Where the death of the patient has become medicalised, that is it has become a medical problem.

As a family member of an ICU patient initially you don’t know what is going on, you don’t understand the systems. During those four and a half months I became very engaged emotionally, intellectually and creatively with that situation and the transition from life to death.

So, four or five years after my father’s death, I started to make work about that time. I decided to make three installations in place or sites that I felt were important to how he thought about himself. So, the first installation was in the church in Aberdeen, the town near where both of my parents grew up. Located in country New South Wales in Australia, this is a former meatworks town and now a dormitory suburb for the coal mines further down the Hunter Valley. It’s predominantly a working-class town.

This installation was raw and emotional. It was constructed from three individual works. The first was a textile work where grey blanket fabric embroidered with the numbers of heart rate, blood pressure and oxygenation as recorded in the bedside medical monitor was wrapped around the church kneelers

For the second work I was able to remove one pew from the church. In its place I put three small beds/tables made of aluminium with old fashioned bed wire mesh across the op. From that hung 22 fat catchers and one chip fryer on which I buttoned 23 squat red crosses. These came from a story or something I half-remembered. I have no idea if it’s actually true, or if I just made it up, or if I compressed it from a couple of different bits of stories. I think it was something I was told when really early one morning after we had all been rung up and asked to come in because the staff thought dad was going to die. When we got there, he was trending up and I think the nurse told me that she had given dad 23 units of blood, which he had then bled out internally into his stomach cavity. At first, I became incredibly aware of how I was dependent for his survival on the donations of blood by 23 individuals. Later it seemed an extraordinary amount of blood to be pumping in to one patient.

The other work was made of two small hospital instrument trolleys pushed in between the pews as if they were members of the congregation. On one was a series of photographs that was set out as if they were medical instruments. The photographs were of the slightly desolate streetscape around the hospital. Several buildings were undergoing renovation during that time and no building looks its best during renovation. The melancholy and despair that I was feeling was reflected in the documentation of these signs of the abject in the physical structure that was supporting the life of my father.

When this exhibition first opened in the church, it turned out to be the first day of the local Pumpkin Festival in the town. And that meant that people could come in and see the exhibition without it being a big deal. During that first day I told my story of how my father died and visitors in return very often told me their stories, particularly if it related to the death of their father. And from that experience, I learned to really value the function of art where it can serve as a catalyst for conversations around really profound subject areas that aren’t normally talked about on a day-to-day basis. It was almost as if people wanted to talk about the deaths, they’d experienced to someone that they thought was interested. And it’s as simple as that, really, I think. It’s a sharing of similar experiences. We’re different in lots of ways age, race, gender, political views, religious views, lots of things but we all understood the importance of that transition from life to death as an experience of life.

The third and final installation was at the School of Physics at the University of Sydney, my father was so proud of being a physicist. The foyer of the School of Physics has a small museum of objects that had been used to see and to measure things in various ways. While I was developing the work there, I met a physicist, the late Dr. Peter Domachuck, who was working on a way to be able to determine the properties of blood while it was still within the body to replace the need to take a sample of blood and then send that blood off to a laboratory to be tested. One property of blood that is commonly determined without being extracted is oxygenation. The material that he was interested in using for this process was fibroin, which is one component of silk. We decided to collaborate and we were later joined by a writer, Dr. Leanne Hall. We didn’t make things together. Instead, we went out to lunch and talked, reinforcing the importance of conversation in my work to the extent that I describe conversation as one of the “materials” of my practice. This collaboration was called Blood on Silk.

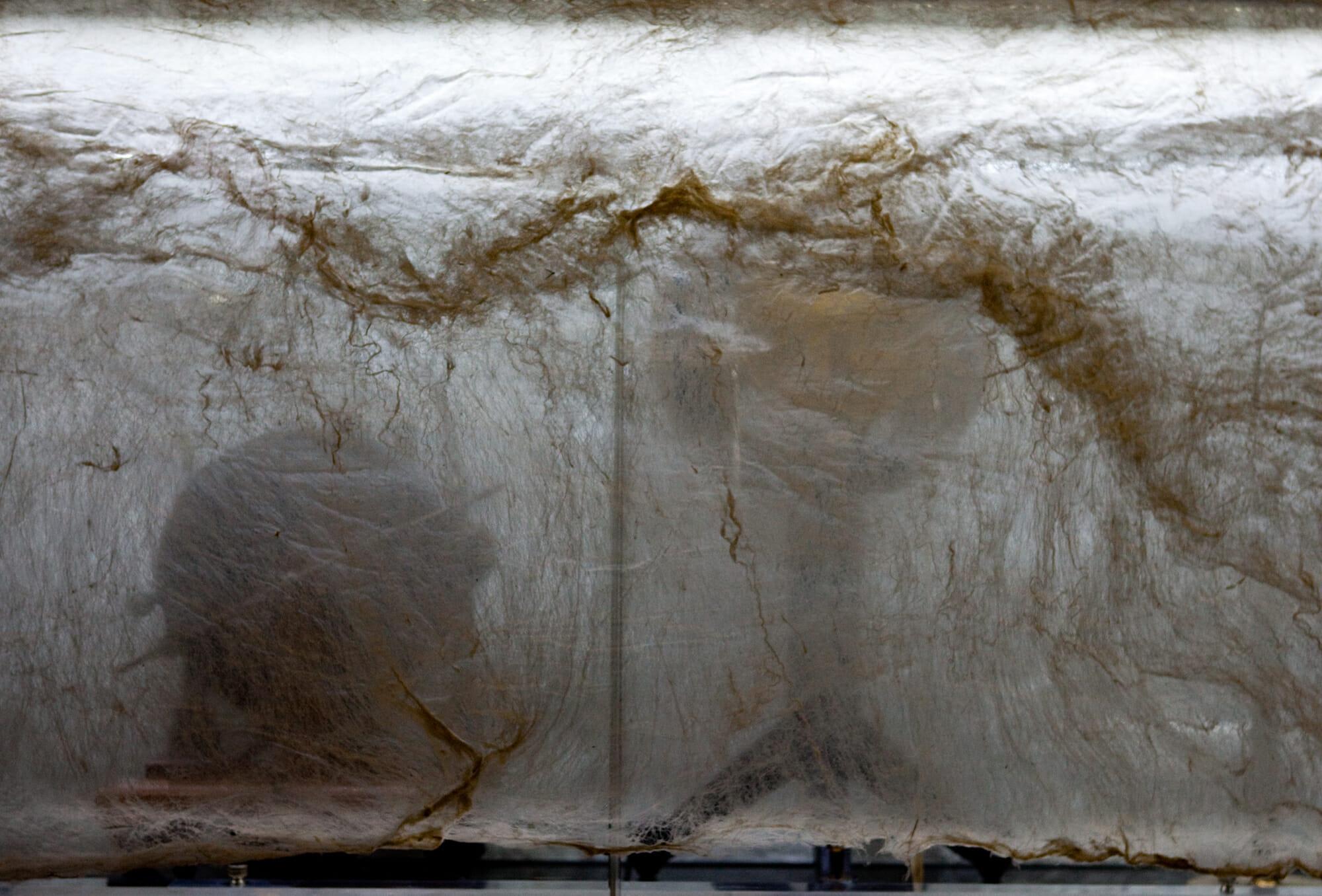

For the first work of this collaboration, I decided to make translucent covers for the museum cases at the School of Physics. I made these translucent covers out of silk. I managed to acquire silk lap, which comes off the end of a carding machine, it’s all parallel and looks beautiful, all in one metre lengths. I was able to make sheets of non-woven textile or paper, large enough to cover the cases so they were about four and a half metres by three metres. Later on, I increased to making much larger sheets which were 10 metres by four metres, which is the size of the lawn in my back garden. I really understood that the fibroin from the silk could be another way of seeing, a way of seeing without vision.

The ideas that have informed and been explored in the Blood on Silk project include the materiality of blood and of silk, the economics of both materials, the supply chains through the silk road, the political, cultural, and the medical context of the hospital and the power structures at play within that site. How all of these come together in the way a patient dies in ICU is the central concern of the project.

What is the genesis of your works – how do you get from the idea to the form of the work?

There are several ways that I approach the making or remaking of a work, depending on whether or not there is a specific time frame for that work to be made. Overall, the conceptual basis for any of my works is the key driver. However, the making, to a physical or performative outcome can modify that initial idea and introduce additional layers of nuance so therefore is of equal value to the idea. I use mind mapping software to keep track of seemingly random ideas, essays, academic papers, and articles and look through them regularly. I have a large number of ideas floating around at any time, and I give them time to crystalise into an initial strategy for making. That strategy is then reviewed and remade during the making process.

If I am responding to a specific exhibition invitation, I adopt a more formal approach. I want to know the details of the exhibition site even if is a “white cube” gallery, then develop ideas and initial works, review, discuss with the curator and resolve. Often the resolution can be forced if there isn’t the time to allow the idea to gel.

Which of your fiber works has most and deeply involved you – emotionally and psychologically?

The work that had a major impact on me emotionally and psychologically was Blood on Silk Last Seen 2017 1silk, video, galvanised zinc sheeting and found objects 12.7 m long by 26.5 m deep by 3.8 m high.

The ground floor of the Casula Arts Centre Turbine Hall is the site of multiple points of transition and multiple points of decision making, some of which relate directly to the architecture and some to the usual patterns or paths of passage in this large open architectural space, resulting in an invisible crisscrossing pattern of use. The most overt point of transition is at the point of entry followed by less obvious multiple points of transition over the entire ground floor as the visitor determines what sequence they will follow or make. At the mezzanine level, the visitor traffic is forced to the perimeters. All of the viewers in this hall are aware of the scale of the space.

Overlaid onto this patterning is the work Blood on Silk: Last Seen. The overarching theoretical concern of the project Blood on Silk is medicalised death in ICU. That is death that is constructed as a medical problem. The points of transition in the process of medicalised death start at the same place – coming through the entry doors either through emergency, or as with Casula and many hospitals, the main front door. Layers of points of transition are then built up through the systems, design and architecture of the hospital – the controls of the visitor entry into ICU, the swing doors into the operating theatres and walking the empty shadowy corridors at night.

In this installation, large sheets of silk paper hang from the ceiling forming five rooms or partially curtained bed spaces. The ceiling is unlit, so the upper reaches of the silk lie in darkness. On to these curtains of silk at just above head height, fragments of images of individuals passing through points of transition in a hospital are projected. The figures, seen from the back, are partially recognisable and partially anonymous.

In the mezzanine gallery the hard lighting of fluorescent tubing starkly refers to the liminal space of the smoking area just outside the hospital buildings. All hospitals in NSW are smoke free workplaces, including all outside areas.

Lying on your back with the hospital curtains drawn, you look up at the ceiling. You notice the curved corners of the curtain track, the texture and opacity of the curtains made of silk paper and the imperfection of the visual and aural privacy offered. In this installation Blood on Silk: Last Seen the physicality of hospital spaces, both those central to the process of treatment and the liminal spaces such as the half-lit corridors at midnight, are overlaid with the emotional landscape of the users of those spaces. The beauty of the silk paper curtains butts up against the forgotten and brutal aesthetics of the ceiling.

The size of the work was daunting however the result was amazing.

What do you think is the meaning of art in the life of ordinary people?

The meaning of art can play a huge role in the life of ordinary people. My experiences with the works on my father’s death in the Aberdeen Church in country NSW showed me how powerful the connection could be between the lived experiences of ordinary people and artists, with art produced from those experiences through the use of conversation. Because my family had come from that town the visitors were not expecting to be disrespected and so were able to relax and give themselves the time to engage with the works.

I also have a very broad understanding of what is and isn’t art and I believe that the rituals of daily life can be thought of as a deep and developed interaction with an individual’s own art making practices, even if they don’t call it by that name.