“Flowers”and “Maple Tree”: interview with Helena Hernmarck

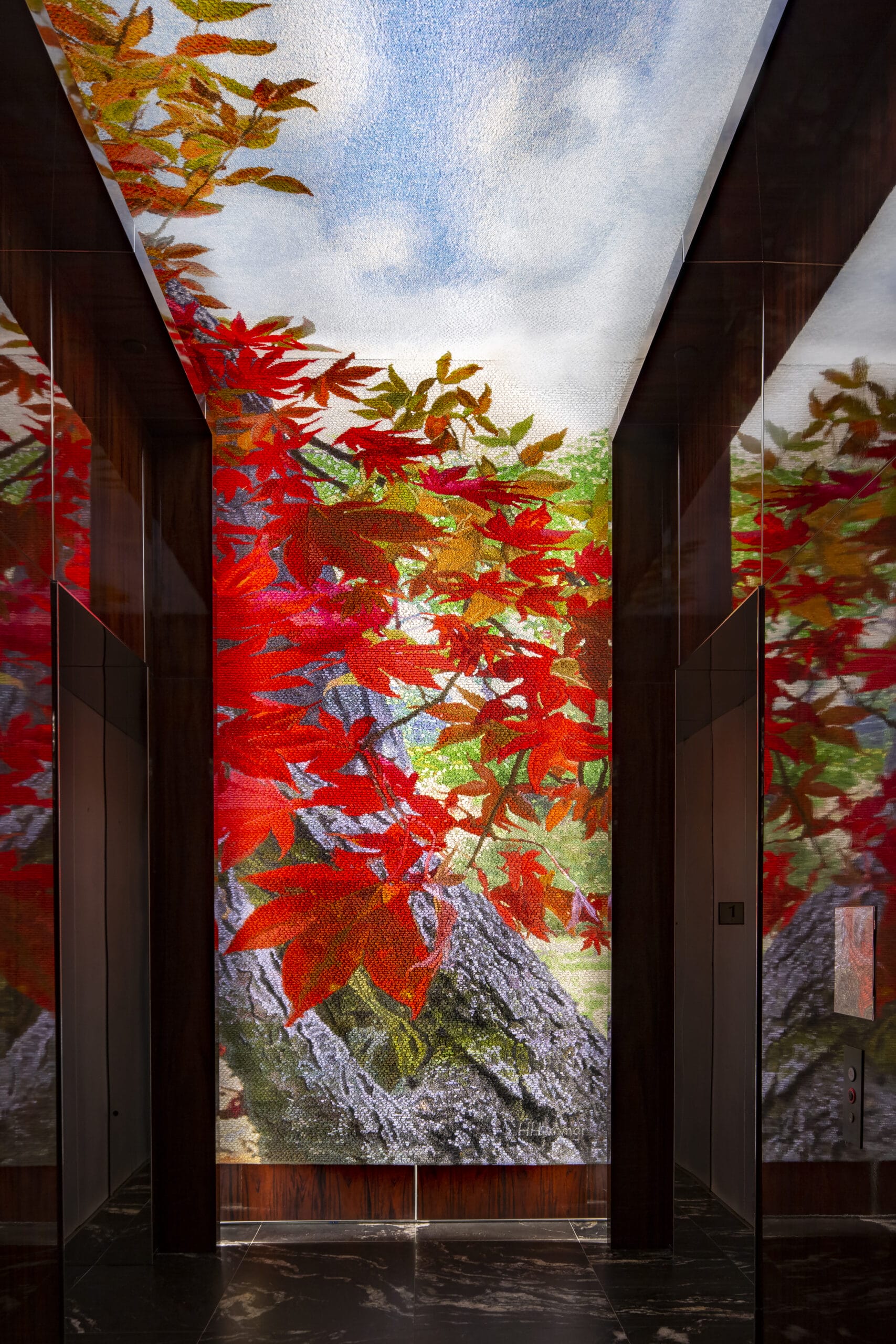

The Swedish artist of international fame, Helena Hernmarck, has recently completed two installations of immersive tapestries created for the residential lobby of the Hudson Yards (New York), showing a unique blend between textile and engineering skills.

The installations, whose titles are “Flowers” and “Maple Tree”, are the results of a long and complex planning and realisation project. The two monumental textiles develop from the floor up to the ceiling and will be seen one at the time, switching every six months.

Hernmarck’s career has established its roots more than fifty years ago, during which the brilliant artist was able to make a great revolution in the tapestry’s aesthetic and connection with the modern architectural spaces. Her style is based on the ability of capturing light and colour realizing chromatic and textural effects which create changing images: from far away the tapestries appear as huge scenery, unified and well-defined images but, getting closer, these same images fade into undefined and abstract visions.

Over the years, Helena Hernmarck’s works have “made alive” dozens of important buildings in the United States, her tapestries are exhibited in several collections of important artistic institutions as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art of New York City, the Chicago Art Institute and the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

“Maple Tree”, photo Norman McGrath, copyright Helena Hernmarck

Helena, “Flowers” and “Maple Tree” are the two monumental tapestries you created for the Hudson Yards in New York. How did this project come about?

I have, over the past 50 years, produced more than 270 tapestries. 115 of these were made on commission, often in collaboration with architects. The Hudson Yards project came about because of two people. One was the architect David Childs of the architectural firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, and the other was his client, Stephen M. Ross. I had known Mr. Childs for decades, and met Mr. Ross in 2003 when he commissioned four tapestries from me for the residential lobby of the Time Warner Center, which is just off Central Park in New York City. The tapestries depict the Park in four seasons, and are exchanged seasonally, every three months.

More than ten years later, in 2016, Mr. Ross approached me again about a commission for Hudson Yards, an area just north of Chelsea in New York City. There was a meeting early on in the process that included Mr. Ross, Mr. Childs, and the interior designer, and Mr. Ross suggested that the tapestries be located in the residential elevator lobby at 35 Hudson Yards, adding that he would like them to extend up the wall and across the ceiling and be exchanged every six months. Having never done such a thing before, or even contemplated it, I immediately followed my own advice: ‘always say yes.’ I had no idea how to do the ceiling installation, but I figured we would work it out.

Your tapestries are architectures that interact with the space creating an immersive, exciting and involving effect. This is the result of a long research and design activity (I am thinking of your trompe l’oeil technique). Can you tell us about it?

Early on in my career, I decided that I would aim to put my work in large architectural spaces. This comes from the tradition I grew up with in Sweden where architects used handmade textiles to bring warmth to lobbies. Tapestries are expensive to make, and I felt it was best to hang them in public spaces. In order for them to occupy a room in an exciting way, I developed my weaving technique so that, close up, the tapestries look abstract and at a distance they come into focus. This works, of course, in a large space, and when I’m designing I’m focusing on scale.

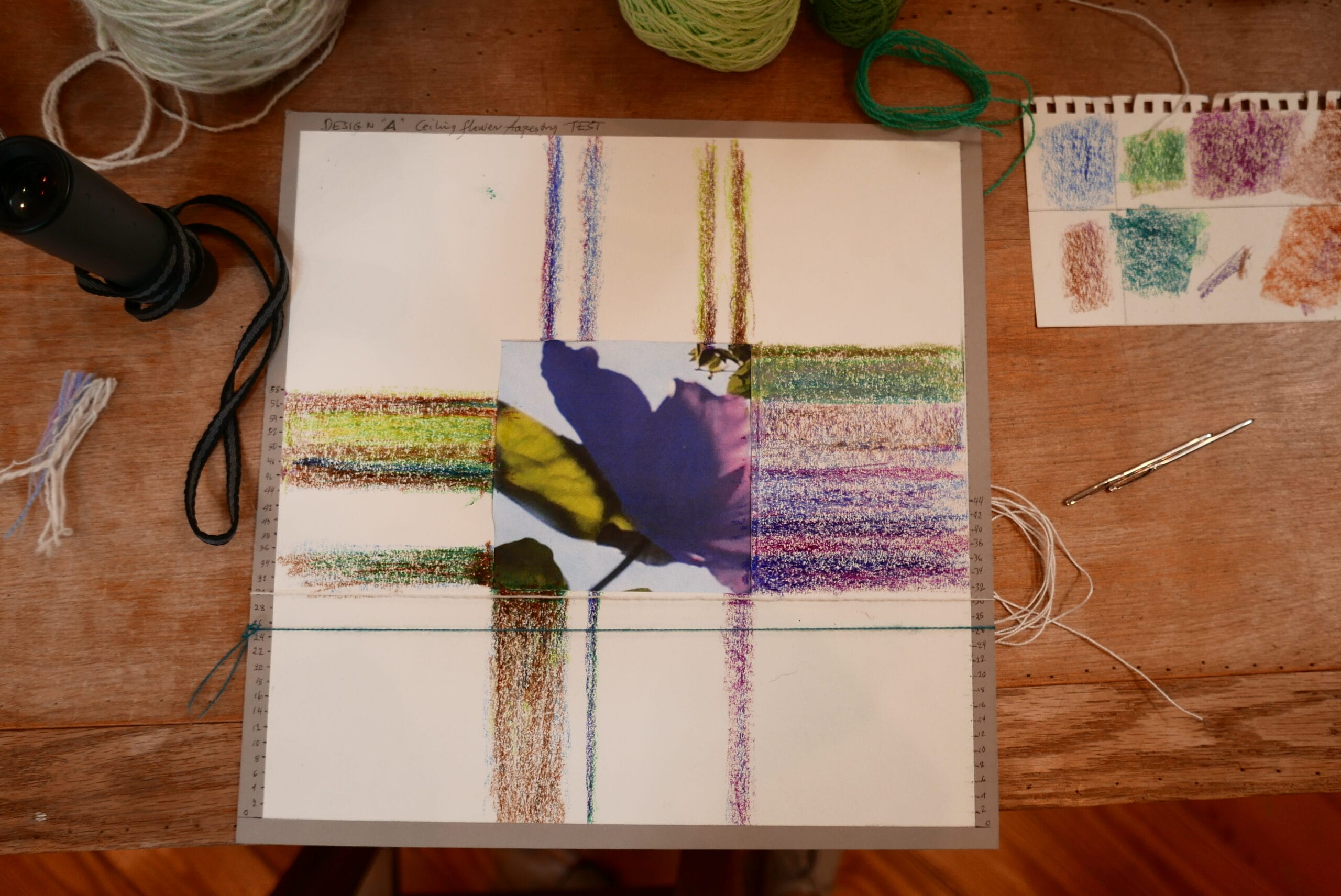

My technique combines rows of discontinuous plain weave with a supplementary pattern stitch, like soumak, that allows me to achieve an illusion of depth through very subtle color mixes in the butterflies. In a way, I’m assuming that the brain is going to fill in the missing information, which seems to work. It’s very much a perception thing, which intrigues me endlessly.

One tool of interest is a monocular that I look through backwards as I’m weaving to be able to see how the tapestry will look from a distance. This, I was taught by my teacher at art school, Edna Martin. She taught us two things. First, to use the monocular, and second, to make our design enlargements, or cartoons, photographically rather than with graph paper. In this way the cartoon captures the movement in the original design. I use a small-scale design to determine the color mixes, and I have a vast variety of colors and textures and thicknesses of yarn on my table next to the loom. In fact, I have hundreds of colors on the table, and one butterfly can contain as many as 15 different strands of yarn. In this way I can incrementally shift the color to match the design as I go along to really capture gradations between the tonalities.

What are the criticalities, the difficulties you had to face to complete such an impressive commission? What challenges did you face?

The first challenge was to come up with the right designs for such a unique space. It came to me in meditation that the elevator lobby was the same shape as a regular cardboard box, so I took a cardboard box and cut holes in it to correspond to the shape of the wall and the ceiling tapestries, and a third hole in the floor of the box to put a camera through. Then I went out with my assistant, Mae Colburn, and we photographed through the box to give me an immediate sense of the composition inside the elevator lobby. At the time, I was unaware of the shift in scale that would result, caused by the box being so small relative to the elevator lobby. So, Flowers and Maple Tree became very enlarged. I loved the idea of being in an enclosed space, like an elevator lobby, and experiencing a sense of sky above your head. It was very unusual.

The second challenge was how to install something in the ceiling that is 2.5 meters wide and 4.7 meters long. I had to make sure it would lie flat, and I had to make sure it could be exchanged every six months. A friend who had worked on film sets gave me three pieces of advice: make it safe, make it easy to exchange, and don’t fight gravity. That was the guidance we followed. We couldn’t use Velcro or magnets because that would fight gravity, so we created a fabric backing for the ceiling tapestries that holds a series of carbon fiber tubes. The tubes span the tapestry widthwise and are supported by ledges built into the adjacent walls. It turned out that for the full length of the ceiling tapestry, we needed approximately 180 carbon fiber tubes, spaced one inch apart. The backing material was pleated, then stitched, to create hundreds of channels, one for each tube. Then the backing was hand-stitched to the tapestry.

This was a huge amount of work. My studio was enlivened for months by a group of stitchers sitting here stitching the backing to the tapestry with tiny, invisible stitches. They were quilters and weavers and artists themselves, and we had textile conservators come and give us advice about what thread to use, what stitches to use, and how tight to draw the thread. One of the major things we learned was that the two layers should coexist comfortably, without pulling, and that the materials should be sympathetic. We used linen thread to match the linen warp, and wool fabric for the backing to match the wool weft of the tapestry.

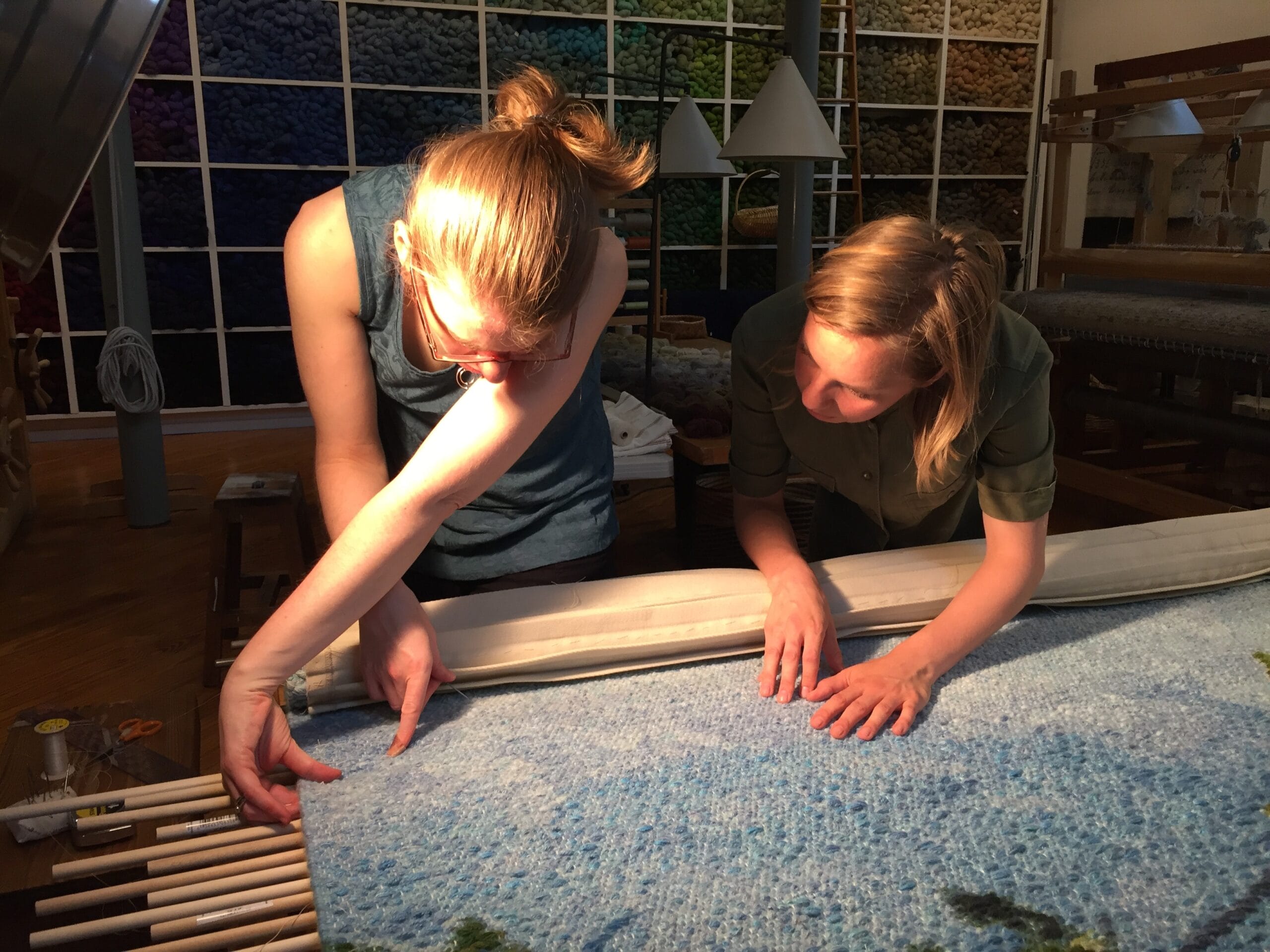

I should also mention the testing involved in completing this part of the commission. We actually spent three months in late 2017 weaving a 2.5 by 2.5 meter test tapestry (an abstraction of the original design) just to have something to test the ceiling installation with. Then, Jim Sortor, who works as a product designer for my late husband’s firm, Niels Diffrient Product Design, built a full-scale mock up of the top eight feet of the elevator lobby in my studio. We tested the ceiling tapestry installation dozens of times and eventually found out that the ceiling tapestries should be woven in two halves to accommodate the six-month rotation. We joined the two halves using a 2.5 meter long zipper. It was a tremendous amount of engineering.

What are the timescale for the realization of such an important project? Who are the craftsmen who have collaborated in its execution?

The two major craftspeople were the weavers, Ebba Bergström and Tova Wibrant, at Alice Lund Textilier in Borlänge, Sweden. I apprenticed at Alice Lund Textilier in 1960 and 61, and the original owner of the studio, Alice Lund, was my mentor. Over the years when I started to get commissions for lobbies in the U.S., I began working with Alice Lund Textilier to produce some of my larger commissions. In total, they have produced 26.

My technique is very specialized in the sense that the weavers have to learn to think like I think, and see like I see, and having a background in Swedish weaving makes it easier to learn. I was also keen to see the weaving tradition in Sweden continue, and for skills to be passed on to younger generations. The current owner, Frida Lindberg, feels similarly about keeping weaving skills alive and made sure that Tova Wibrant, the younger of the two weavers, worked on the Hudson Yards commission to be able to hone her technique. Frida led the entire production end of this commission, including working out the timing and the cost. It took four years to weave the tapestries. Each wall and ceiling section took one year.

Although your installations have a clearly contemporary imprint, what do they preserve of the ancient tapestry tradition?

When I started out I certainly felt I was following in the footsteps of Penelope, and all the Renaissance tapestries that were very recognized as an artform. I felt that I wanted to do the same thing in a contemporary idiom. It seemed the best way to go if I wanted to support myself and an entire community of people including the weavers, the dyers, even the farmers. I’m very invested in keeping the skills going, the skills to deal with wool, with yarn, and weaving.

It was also clear to me that it was historically common that these large tapestries were made to fill whole walls, to create rooms, and that’s what I wanted. I felt that weaving large-scale tapestries was a stronger way to go than, for example, painting because the weaving has texture, which print or paint on paper or canvas often lack. The wool itself gives the tapestry an enormous advantage in terms of presence.