The Lingering Presence of Absent Bodies in Judy Rushin-Knopf’s Textiles

di Ivy Brown*

The process of tufting requires the artist to work from the backside of a canvas. This inversion suits artist Judy Rushin-Knopf’s preference for open-ended process perfectly. Even when she was working with more conventional painting materials — she was trained as a painter – she preferred to work in frameworks that allowed her process to be provisional and indeterminate. In her tufted textiles, this point of access from the ‘other side’ takes on metaphysical significance.

In 2014, her husband became ill with what was eventually diagnosed as a rare and aggressive type of lymphoma. Long bouts by his side in hospitals introduced them to what Susan Sontag called the “kingdom of the sick” and the sense of non-linear time that goes with it. Rushin-Knopf began to make radically different work that she claimed was sent by a fictional character from a parallel dimension or alternate timeline. The character, W.C. Wen, was a former student whose work Rushin-Knopf collected, envied, and plagiarized. Wen lives in the past, present, and future. It is worth noting that alter-egos have a long history among artists in all fields. Artists create them for a variety of reasons, one of them being to freely experiment with another side of oneself. Joan Jonas’ Organic Honey and Theaster Gates’ Shoji Yamaguchi are two contemporary examples. The W.C. Wen personae gave Rushin-Knopf permission to make work about this new territory.

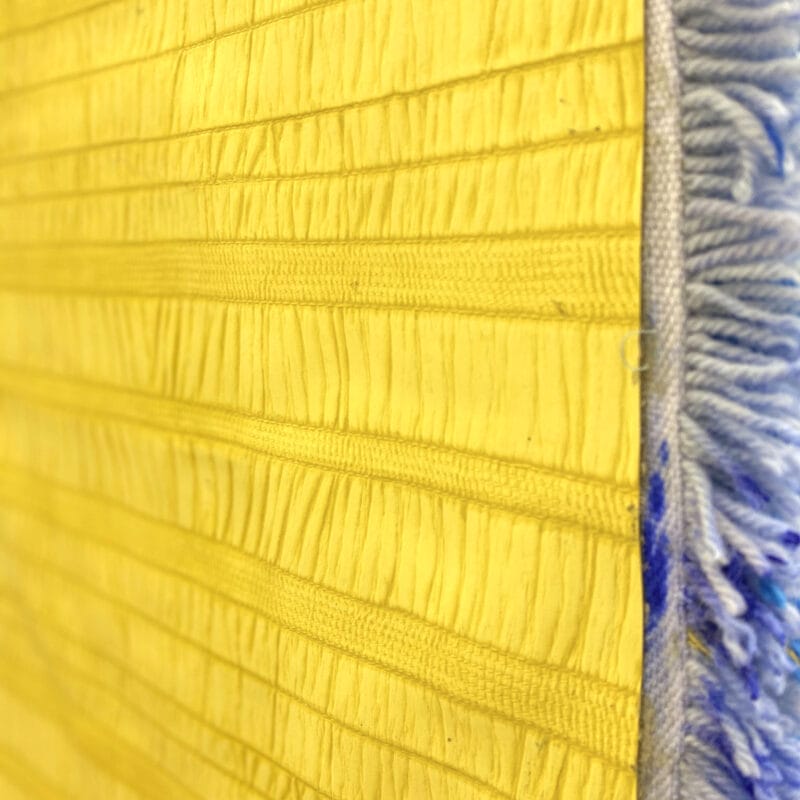

Peter Schjeldahl said “death is like painting rather than like sculpture, because it’s seen from only one side.” Rushin-Knopf’s textiles live somewhere in between painting and sculpture, and if you accept Schjeldahl’s metaphor, between life and death.

Their flatness can be thick or thin. They are worked from back and front. They are 2-dimensional, but sometimes she displays them in the middle of the room so they can be seen from both sides. They are blue, which can be sad or restful. They are sent from another world and another artist, who is also her.

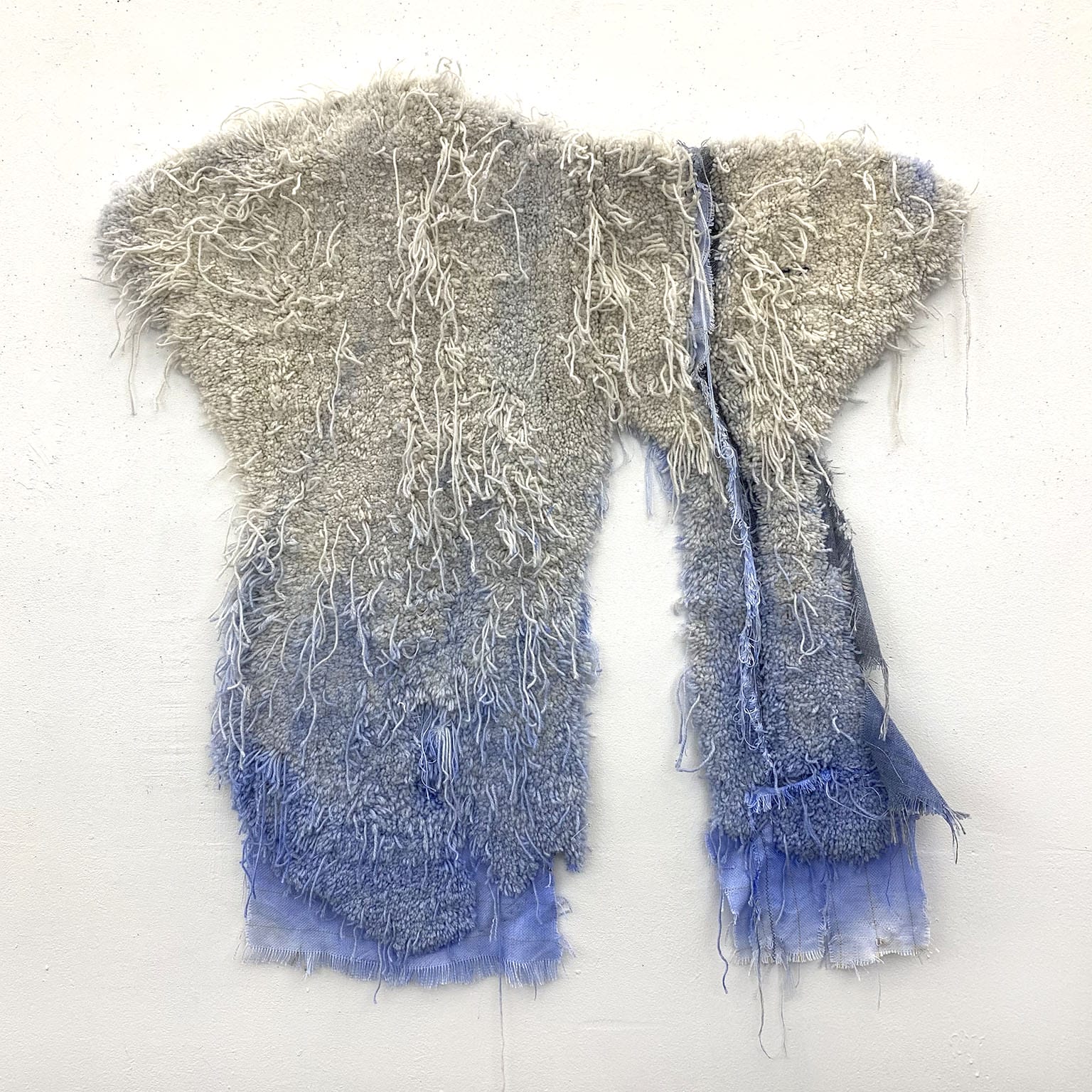

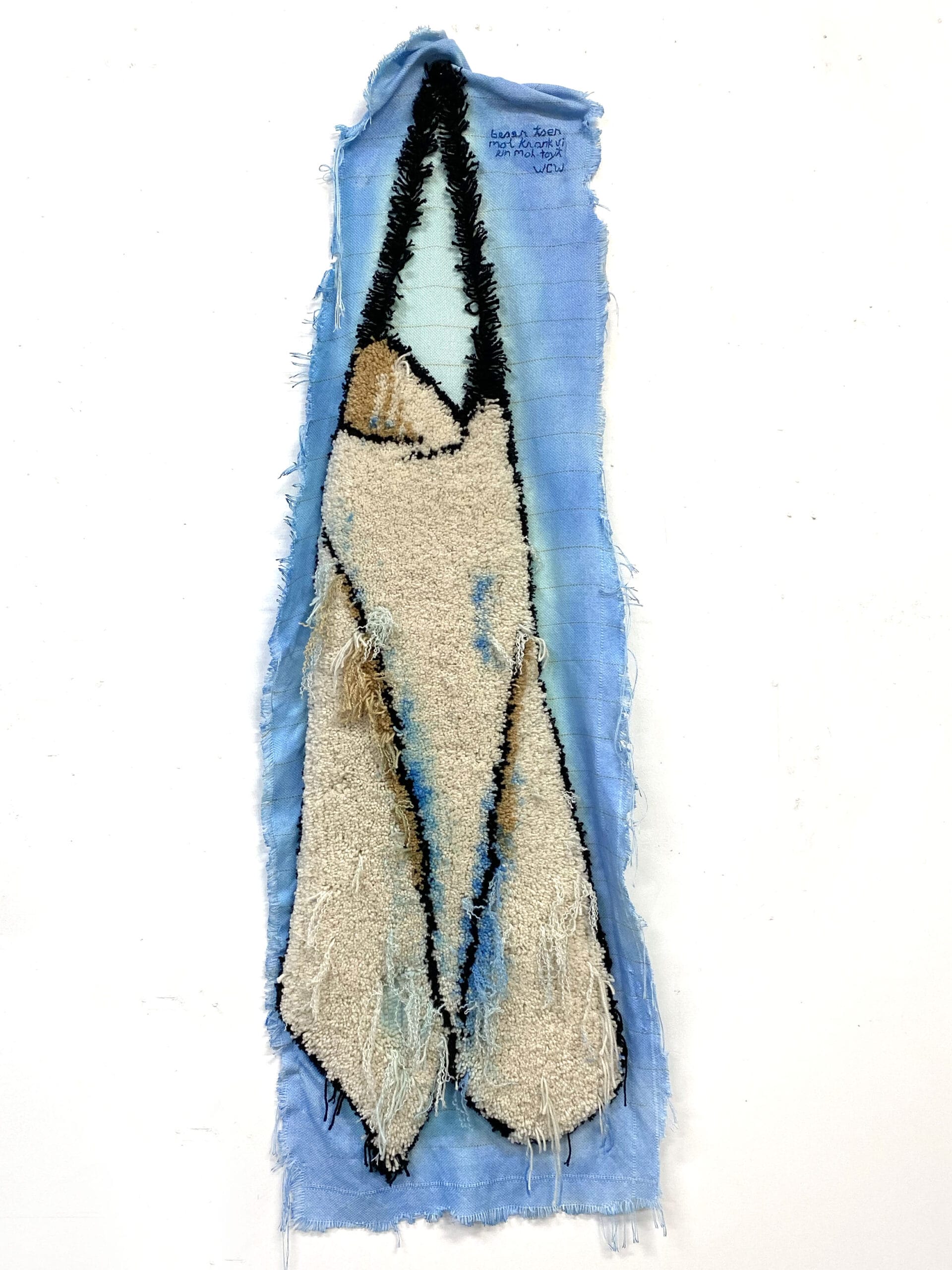

As she witnessed her husband’s identity slip into the one dimensionality of ‘cancer patient,’ she turned first to the hospital gown – it’s flatness and ineffectualness as a covering – to symbolize the deflating effects of illness on social identity. During the following months she explored how clothing, and fashion in general, are equally effective and ineffective as identity signifiers. The fact that Rushin-Knopf uses the materials of clothing to represent rather than make actual clothes – her insistence on flatness, mismatched symmetries, partially rendered garments, and the absence of the body – speaks as much to the fantasy of fashion as it does to the dehumanizing nature of a hospital gown.

If the hospital gown represents weakness, the hazmat suit represents power. After all, Western medicine regards sick bodies as deviant and non-conforming, like recalcitrant teens that just need some discipline. Rushin-Knopf allows herself to play with this (mis)perception, suggesting that as the physicality of a being transforms, so does its psychic nature. In her world, hazmat suits look like sad snuggies, oversized wooly chaps want a giant bare ass, and a button down shirt is reduced to that cheap illusion to fashion, a dicky.

Schjeldal went on to say, in describing his struggle to represent his own illness, that death is “monochrome—like the mausoleum-gray former Berlin Wall, which kids in West Berlin glamorized with graffiti.”

Like Schjeldahl, Rushin-Knopf wants to acknowledge the patient’s dimensionality. Seen as a whole, Rushin-Knopf’s textiles suggest the absence of the body and further, the languishing devolution of physical integrity caused by illness – which she restores with color.

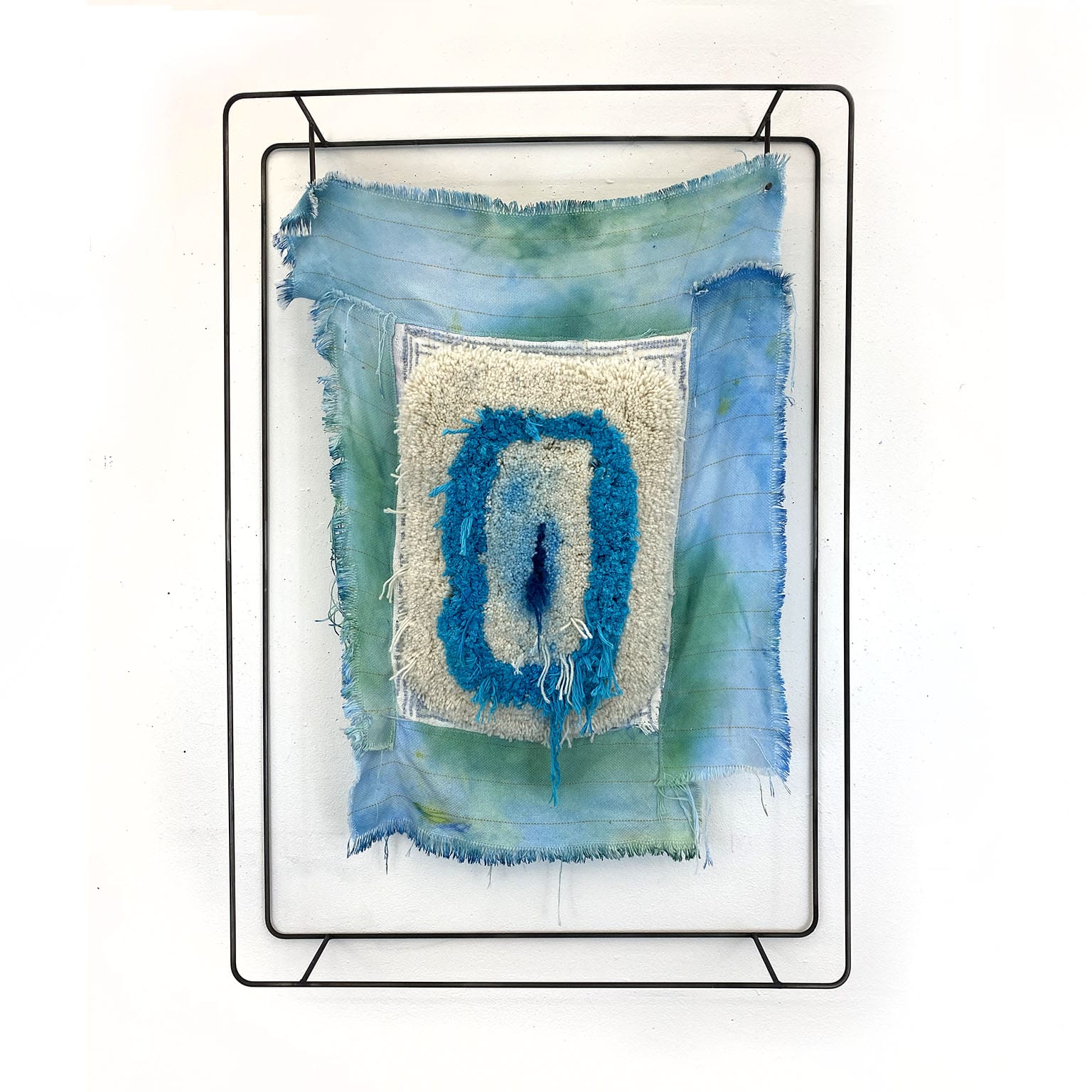

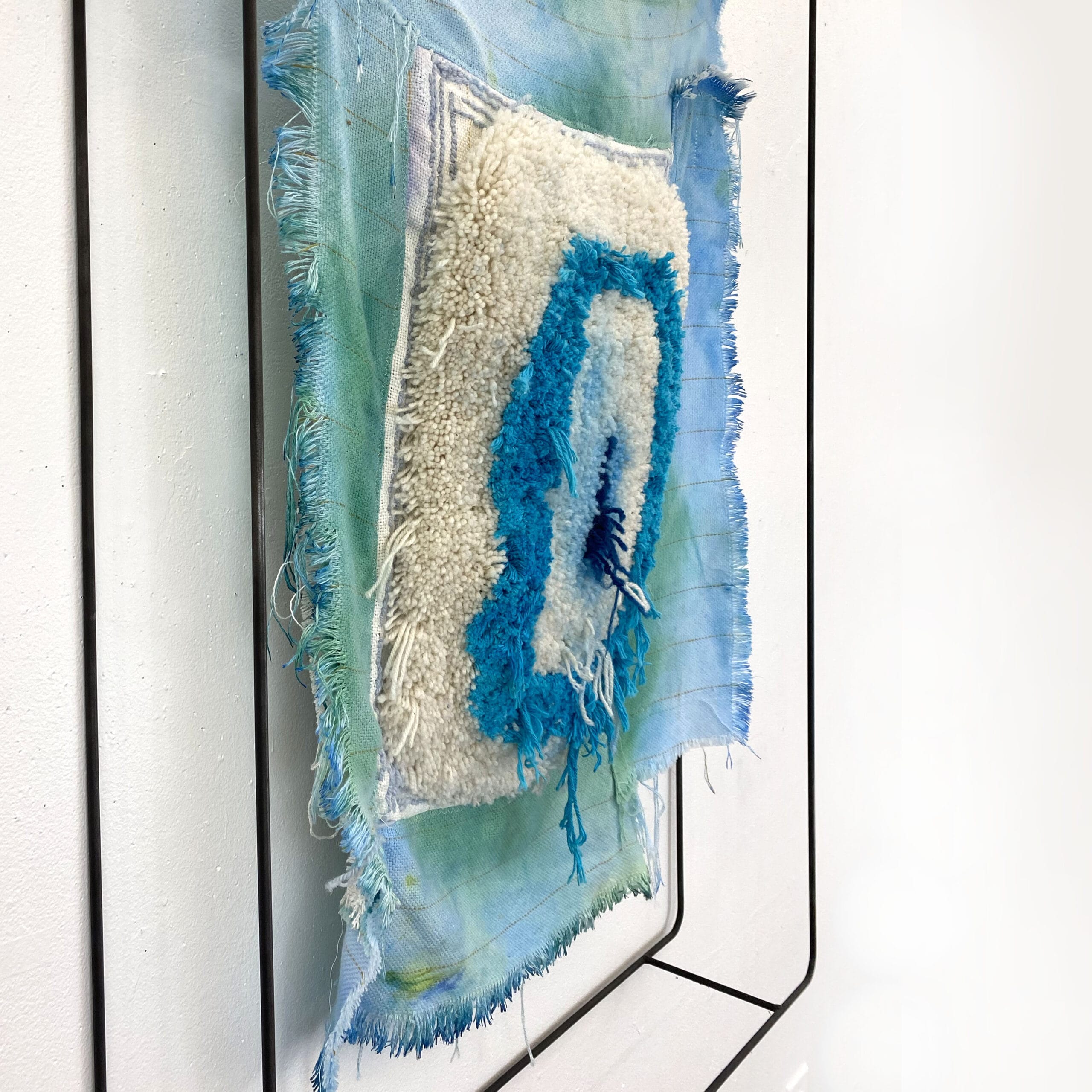

“INCH Coat”, photo cr. Judy Rushin-Knopf, copyright Judy Rushin-Knopf

Rushin-Knopf prefers to paint her textiles rather than using colored yarn because it allows the textile to act as an armature for fluid, spontaneous marks. Her current body of work is predominately blue with punctuations of bright yellow or rust orange. In 2011 she made a series of monochrome paintings based on blue hues pulled from a photo of a Mediterranean sky. Her ten-year-old son, who had the flu, cut the photo out of a magazine because it made him feel better. So she made a series of 10 little paintings on broken boards (to suggest broken bodies), each hung low to be viewed from a chair provided by the artist. These little fever meditations titled Neti Pots For Your Eyes echo in these new textiles. While the panels were a direct reference to what the body is, the textiles refer to what the body wants.

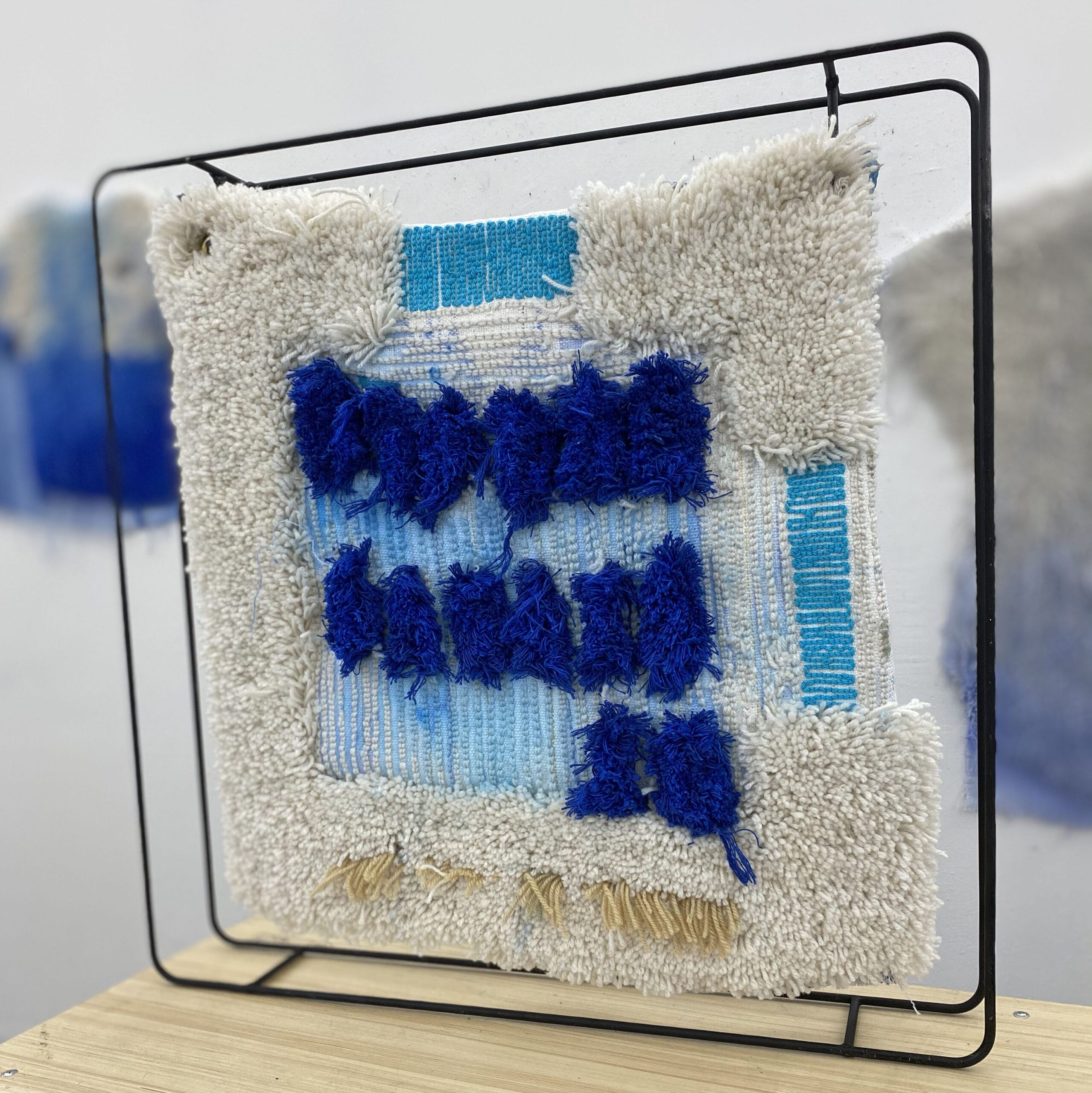

“Semitic”, photo cr. Judy Rushin-Knopf, copyright Judy Rushin-Knopf

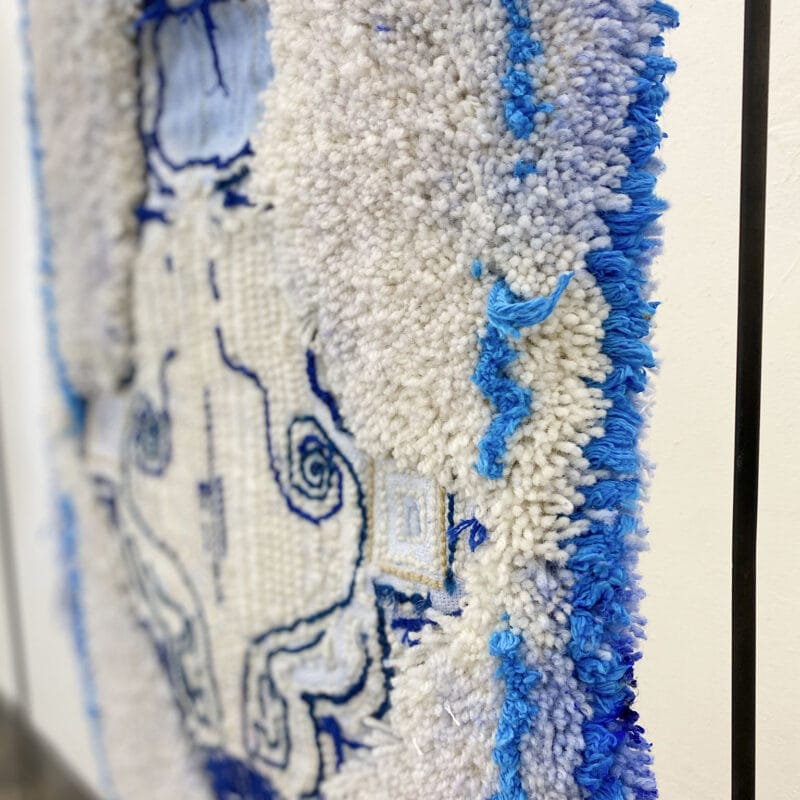

To construct her textiles, her work requires more bodily strength than it did when she was in her twenties. Now in her early sixties, she hauls her large tufted pieces outside and hoses them down so they’ll accept the dyes and acrylics she uses for painting. She describes this part of the process as “wrestling, using my whole body to move the wet ‘rugs’ that, depending on size, can get damned fucking heavy.” She pours and sprays the dyes and paints or dips parts of the textiles into small vats of dye. She then walks across the thick piled surfaces to work the color into the fibers.

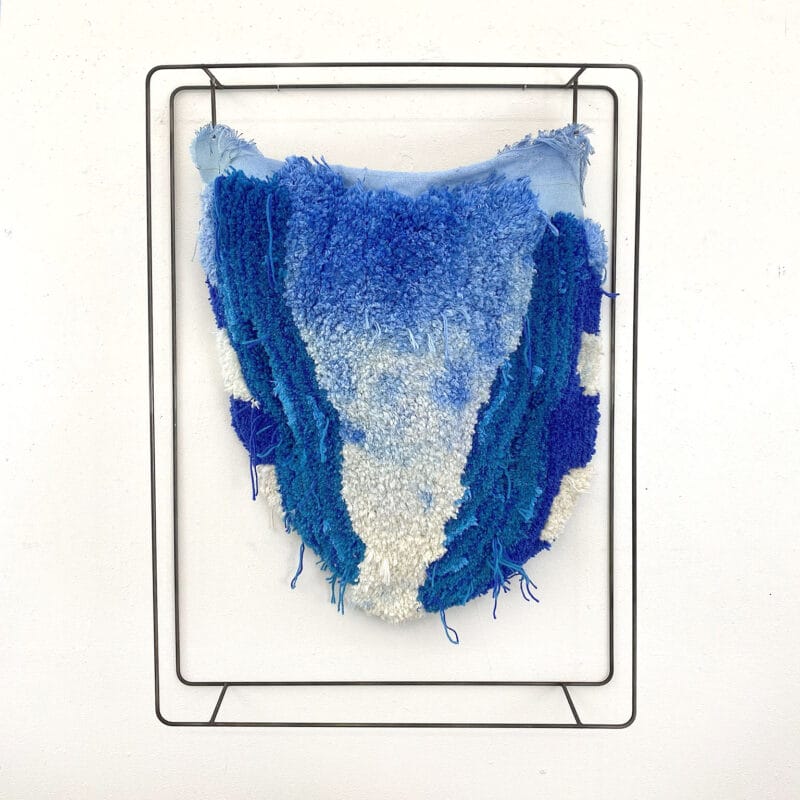

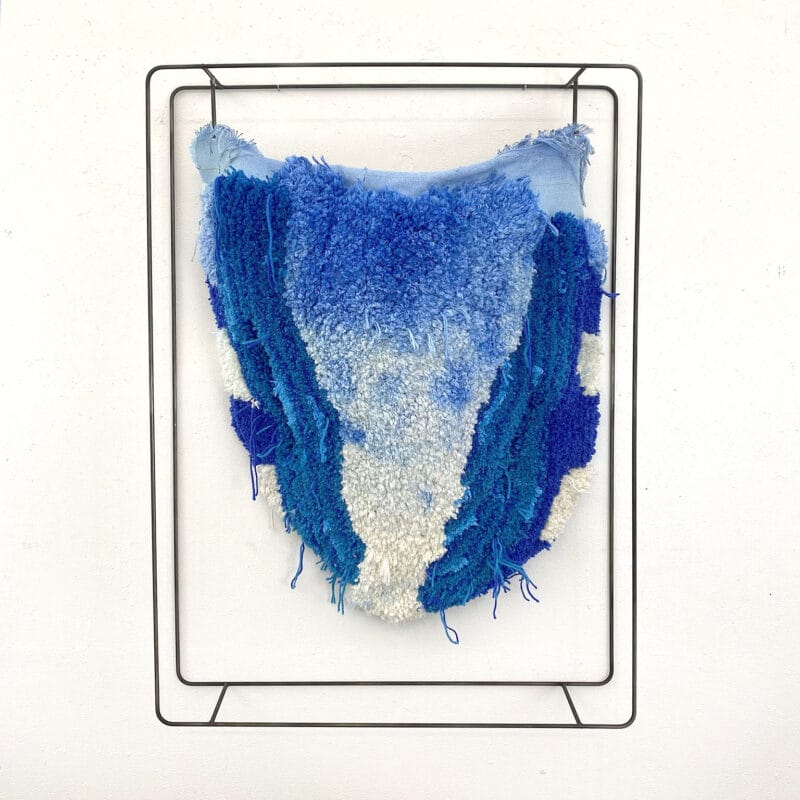

“Collar”, photo cr. Judy Rushin-Knopf, copyright Judy Rushin-Knopf

“Collar”, photo cr. Judy Rushin-Knopf, copyright Judy Rushin-Knopf

“Collar”, photo cr. Judy Rushin-Knopf, copyright Judy Rushin-Knopf

The result, according to critic Logan Lockner in Burnaway, is a lingering presence of absent figures—not only through the implied shape of a body but also the unraveling textiles’ material qualities.

We all know how precarious the balance is between strength and weakness, health and illness. For Rushin-Knopf, every wrestling session is a reminder that all bodies seek equilibrium. Exert, hurt, heal, repeat. Or, for those initiates, hurt, endure, and maybe die laughing.

* IVY BROWN and her art gallery in New York

Ivy Brown Gallery was founded in 2001 as a result of 9/11 and her commitment to opening doors in her community. The Gallery represents and exhibits contemporary art of all mediums. Dedicated to supporting emerging and established artists, Ivy Brown takes her experience from the commercial arts world and brings it to the fine arts arena. The gallery also curates exhibitions throughout New York City. Ivy’s commitment to art and the critical part it plays in our humanity is the grounding force behind the gallery.