BETWEEN TAILORING, FIBRE ART AND FREEDOM

Caterinette: tra arte e libertà

An exhibition curated by Collettivo LaMasca

In the early 1900s, wealthy families turned to sewists for clothing and linen. This role was so essential that a room in the house was dedicated to this task. Here, threads were woven together with lives, comparing the world of the patrons and the poorest of the sewists who merely witnessed other people’s life. One of these women is the main character of the novel “Il sogno della macchina da cucire” (The Dream of the Sewing Machine) by Bianca Bitzorno. She’s a girl of very humble origins who aspires to rise from her rank thanks to her hard work as a seamstress. We find the same ambition for economic independence in Hester Prynne in ”The Scarlet Letter” by Nathaniel Hawthorne. Characters who are despised by the upper classes but indispensable.

We can find these stories in the real lives of the Caterinette (as the dressmakers and milliners in Turin were called), taking their name from Saint Catherine, chosen by the French apprentice stylists because, at the beginning of the century, the Piedmontese capital was considered the capital of Italian fashion.

Tailors cost too much (they were paid about twice as much as women), so they turned to the Caterinette, called “sartine” in a mocking tone; this job allowed them to have a certain economic independence without necessarily having to find a husband to lead an independent life.

The room dedicated to sewing, a symbol of independence, recalls Virginia Wolf’s ‘A Room of One’s Own’, which reminds us that the restrictions imposed over the centuries on female creativity by society, laws and conventions should be challenged.

Another author, Rozsika Parker, in ‘The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine’, considers the relationship between women and textile work. The author pushes embroidery out of the world of domestic intimacy into that of the fine arts, creating a major breakthrough in art history and criticism and fostering the emergence of the craft movements that are expanding today. The separation of embroidery from the fine arts was an essential element in the marginalisation of women’s work: such work has always been classified as handicrafts.

The hierarchical separation between various art forms is usually prompted by the social and economic system and class-related criteria, just as there is a connection between the art hierarchies and male/female sexual stereotypes.

The divisions emerged during the Renaissance, when embroidery was widespread among women working as amateurs, in their homes and without payment.

Art and embroidery were antipodes, the former predominantly produced by men in the public domain and for money; the latter mainly entrusted to the hands of working women or disadvantaged lower/middle-class women in the domestic realm. A gesture made purely for ‘love’, trivial and unnecessary for a specific purpose other than adornment. The term arose from an idea of femininity as a form of service and selflessness, stressing how women work for others; thus, the work’s content is subordinated to a delicate and decorative form.

Rather than acknowledging that embroidery and painting are different activities but possess equal artistic status, embroidery and the crafts associated with the ‘second sex’ are given a lower value.

This form of expression cannot be considered a craft as it does not fulfil a utilitarian purpose; embroidery, to a great extent, is purely pictorial. In the 18th century, it was considered an appropriate activity for women because of their inherent physical frailty. For this reason, feminists, for a while, blamed it for any restriction on the lives of women engaged in fighting.

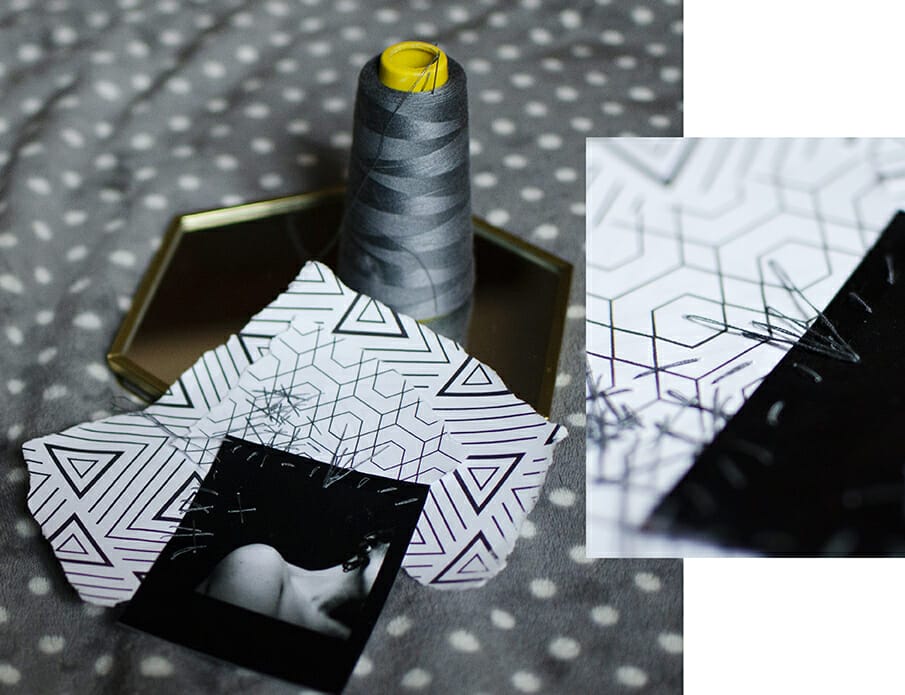

The art of embroidery is undoubtedly a cultural practice involving iconography and style, with a significant social value. Today, the theme of needlework has turned into fibre art: a means of breaking down the traditional divisions between fine and applied arts, especially those considered feminine. Moreover, fibre art is an autonomous expressive language, a declaration of independence through the very choice of the textile medium.

The LaMasca collective (made up of Letizia Imasumaq Huancahuari Tueros, Anastasia Talana, Giulia Lungo and Anna Bassi) will be involved in an exhibition to honour the Caterinette and everything they represent.

THE EXHIBITION ‘CATERINETTE: TRA ARTE E LIBERTA’

Where: Spazio Ruggine Home Gallery, via Cenisio 62, Milan

Dates and times:

25 November h 18:00 – 21:00 (vernissage and talk)

26 November h 18:00 – 21:00

27 November h 18:00 – 21:00 (finissage)

On the occasion of the ‘International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women’, there will be a talk addressing the topic chosen for the exhibition and the meaning of this important day.

The speakers will be:

– Margaret Sgarra, contemporary art curator and art historian, will talk about the relationship between tailoring, textile art and empowerment;

– Anna Bassi will present the app Inside, a dissertation project on the archetypes of the feminine, conceived in 2021 by Alessia la Salandra, artist-therapist, Doctor in Applied Behavioural and Cognitive Psychology and teacher. The application has been created in collaboration with Ilaria Fattori, a Doctor in Architectural Design and functional analyst who coordinates projects aimed at digitalising public administration processes, and Anna Bassi, a textile artist and member of the LaMasca collective.